Medical Apartheid: Teaching the Tuskegee Syphilis Study

When I think of Black Lives Matter, what comes to mind first is police brutality and the resulting lost lives of young men and women in recent times. But as a science teacher, I know that racism in the United States also has roots that extend deep into the history of medical research.

Medical apartheid, the systematic oppression and exclusion of African Americans in our healthcare systems, has existed since the time of slavery and continues today in medical offices and research universities. What care people receive, what diseases are studied, and who is included in research groups are still delineated by race.

The term medical apartheid is explained in Harriet Washington’s 2007 work, Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. Washington documents how “diverse forms of racial discrimination have shaped both the relationship between white physicians and black patients and the attitude of the latter towards modern medicine in general.”

Medical apartheid is a reality that many of my students and their families face. I teach in the only predominantly African American high school in Oregon. Being talked down to by doctors is a common experience, as is leaving the doctor’s office without receiving adequate care. One of my students told us that her uncle’s treatment for a heart condition was so substandard, her family sued the hospital for discrimination. Critically examining the history of medical research is a way to bring the experiences of my students and their families into the classroom, and a way to connect our study of bioethics to the often hidden history of African American men and women who fought for their dignity and rights against a medical system that treated them like lab rats.

So I begin my Research and Medicine course, a senior-level course in our Health Sciences and Biotechnology Program, with an exploration of bioethics, a theme that continues throughout all of the units. We focus on the Tuskegee Syphilis Study (TSS), a chapter of scientific and medical history rarely discussed in high school. Particularly as a white educator, I am conscious that leading the school year with a unit on a deeply painful example of Black oppression needs to be done with care. is is the capstone course of the program, and I already know the students when the class starts. Without a level of trust and mutual respect already established, this unit would not be as successful. If I did not know my students well, I would wait until later in the year, after a safe space had been created. Another reason to wait is that the TSS leads to discussions about cell types (particularly types of bacteria) and epidemiology, which are typically covered later in the year.

Day one of the unit starts with me asking a simple question: “In what ways are you in control of your health and in what ways are you not in control?” I list a couple examples: “I’m in control of how often I exercise but I’m not in control of air pollution in my neighborhood.” The students do a think-pair-share with the question, scribbling down answers and then sharing with their lab bench partner.

As we start to answer the question as a whole class, I write their answers on the whiteboard under the headers “In Control” and “Not in Control.” Pretty quickly, someone disagrees about the appropriate header.

“One way I’m in control of my health is what food I eat,” Robert says. I write “foods” under In Control.

Charene asks, “What if good food isn’t available?”

Kia yells out, “Our school lunch is terrible but it’s free. Is that a choice? I don’t eat that junk!”

After more examples are generated, I ask: “Who does have a choice about what food they eat? Why do some people have different levels of access to doctors? How come some neighborhoods have better air quality? Why can’t some people go running safely at night?”

Soon nothing in the In Control column is safe from my kids’ scrutiny. We talk about each item through a social justice lens. For example, going to the doctor regularly is tied to insurance—which is tied to job and education level—and access to transportation. Exercising is linked to living in a safe neighborhood, child-care, money for gyms, air quality, and concern about what police see when a middle-aged white woman is running vs. a Black or Brown youth. The class inevitably concludes that health and healthcare are a complex mix of choice and circumstance, and that those with more social and economic power have a different level of choice.

Sade sums it up: “None of this is a choice for poor people, just for people who can buy whatever they choose, and who has that kind of money isn’t always fair.”

The Tuskegee Mixer

My students’ insights on these intersections in our healthcare system lead into a mixer on the TSS. The TSS exemplifies how race, class, and healthcare have intersected in this country, all themes the students raised during our warm-up.

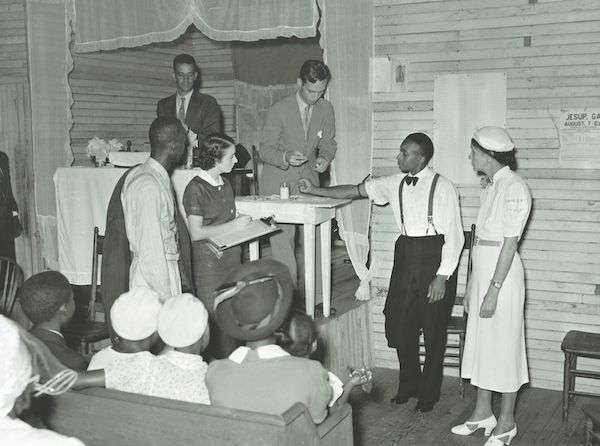

The “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” (now formally known as the “U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee”), which began in 1932 in rural Alabama, spanned most of the 20th century. African American men with syphilis (the sexually transmitted disease or a different strain of the bacteria known as yaws) were observed, yet received no treatment. They were denied standard treatment—heavy metal treatments at first, and later penicillin—and forbidden to seek medical treatment elsewhere. The architects of the study went as far as barring the men from the World War II draft, where they would have been treated with penicillin. The study continued into the early 1970s, when a whistle-blower, fed up with trying to get the attention of his superiors, took the story to a journalist. After the article appeared, Congress held hearings that suspended the study and led to passage of the National Research Act, which includes a mandated code of ethics for research on human subjects.

“We’re going to look at a time in medical history when informed consent didn’t exist,” I tell the students as I introduce the mixer. I give each student the role of a study subject, a doctor, a public health official, a widow, or a journalist. There are roles that show the damage inflicted, and also roles that show the resistance and whistleblowing that ultimately exposed and ended the study. For example:

Charles Pollard was a participant who later became an activist:

I am a Macon County farmer, and I started in the Tuskegee Study in the early 1930s. I recall the day in 1932 when some men came by and told me I would receive a free physical examination if I came by the one-room school near my house. So I went on over and they told me I had bad blood. . . . And that’s what they’ve been telling me ever since.

I was at a stockyard in Montgomery, and a newspaper woman started talking to me about the study in Tuskegee. She asked me if I knew Nurse Rivers. That’s how I discovered I was one of the men in the study. Once I found out how those doctors at Tuskegee used the African American men of Macon County in their study, I went to see Fred Gray. He was Rosa Parks’ and Martin Luther King Jr.’s attorney. He took our case and sued the federal government for using us as guinea pigs without our consent.

Being in this study violated my rights. After I found out about the real purpose of the study, I told reporters, “All I knew was that [the doctors and nurses] just kept saying I had the bad blood—they never mentioned syphilis to me, not even once.”

Other roles include Nurse Eunice Rivers and Dr. Eugene Dibble, both African Americans who worked as researchers in the study, supporting the study perhaps as a way to bring both money and prestige to Tuskegee. Roles of the white doctors who designed and orchestrated the study include upsetting quotes. For example, Dr. Thomas Murrell, an advisor to the study’s leaders, said:

So the scourge sweeps among them. Those that are treated are only half cured, and the effort to assimilate into a complex civilization drives their diseased minds until the results are criminal records. Perhaps here, in conjunction with tuberculosis, will be the end of the Negro problem. Disease will accomplish what man cannot.

Once the students read, understand, and are prepared to play the person in their role sheet, I ask everyone to walk around the room, telling people who they are and learning about other participants in the drama.

Their initial curiosity quickly changes to disbelief for some and hardening anger for others. They fill out a question sheet as they meet the other characters, and then spend a few minutes reflecting on questions raised by the mixer, and what surprised, angered, or left them hopeful. “Why did they do this? What did they learn?”

“Why didn’t they give the men penicillin?”

“How long did this last?”

Students start to make the connections between the study and the pre-World War II eugenics movement they studied previously. As David points out, “This is a lot like what the Nazi doctors did in Auschwitz.”

Whistle-blowers

Then we transition into reading the article that brought national attention to the study. In 1966, Peter Buxtun, a U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) venereal disease investigator, tried to alert his superiors about the immorality and lack of scientific ethics of the study, but they would not listen. In 1968, William Carter Jenkins, an African American statistician at PHS, called for an end to the study in a small anti-racist newsletter he founded. Nothing changed. Finally, Buxtun went to the mainstream press, and Associated Press journalist Jean Heller broke the story in the Washington Evening Star. She begins:

Washington, July 25 [1972]—For 40 years the United States Public Health Service has conducted a study in which human beings with syphilis, who were induced to serve as guinea pigs, have gone without medical treatment for the disease and a few have died of its late effects, even though an effective therapy was eventually discovered.

Officials of the health service who initiated the experiment have long since retired. Current officials, who say they have serious doubts about the morality of the study, also say that it is too late to treat the syphilis in any surviving participants.

The students also read the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s description of syphilis, including the progression of the disease and recommended treatment, and a summary I created of other relevant information.

Then I assign some writing: Using these resources and what you learned from meeting everyone in the mixer, write a first-person testimony that could have been used at the congressional hearings that followed Heller’s story. You can be the same person you portrayed in the mixer, or someone else. Explain why you think the study happened, your understanding of the disease itself, and if reparations are appropriate or not. Explain your reasons.

These are quick-writes, not final pieces, but aimed at getting students to understand the human lives behind the medical facts. Lejay writes from the perspective of a widow of one of the men in the study:

I am Ruth Fields and I became a widow during the Tuskegee Syphilis Study. My husband passed away from the effects of syphilis. . . . In the early 1920s, syphilis was a major health issue and concern. In 1932, a study was conducted of 399 men with syphilis and 201 without, the men were given occasional assessments, and were told they were being treated. In 1936, local physicians were asked to help with the study, but not treat the men, and to follow the men until death. Penicillin became a treatment option for syphilis but the men in the study couldn’t receive it. . . .

I endured so much hurt, pain, and loss because of this study, and I just want everyone who was involved to be punished for their actions, because they hurt and killed and destroyed so many lives.

Shirene writes from the point of view of one of the men in the study:

I am Roy Douglas. Poor, uneducated African American men like myself experienced an outbreak of syphilis. We were sent to hospitals for having “bad blood.” Doctors didn’t know how the STD worked, the side effects, or the symptoms. To get the information that they needed, they used us as test dummies. Over 400 of us were denied help, medicine, and the proper treatment for years. Some men suffered from mild symptoms like rashes, then spots appeared on the surface of their skin. With time, their nerves, brains, and more shut down. . . . In 1945, penicillin was finally accepted as a treatment for syphilis.

After more than 30 years of researching, the study finally ended in 1972. I personally feel like the study was a small version of a genocide. . . . It was unnecessary and wrong to use poor, Black men as guinea pigs for experiments. Out of the whole dehumanizing study, the only positive outcome was the cure. ere should have been more rules or procedures set up to maintain the health of the sick men. No one deserves to die when there is some type of medicine to cure them. I believe that every person that lent a hand in the study should have gone to prison.

Where Do We Go from Here?

There is so much of the TSS that is hard to swallow. The sheer length—more than 40 years—is astounding for any longitudinal study, let alone one that watched men die from a brutal infection that attacks the nervous system. The fact that researchers went to great lengths to keep the men from finding out that there was a simple cure shows the purpose was not to find treatment. That the study continued throughout and after the Civil Rights Movement is perplexing and contrary to a narrative of racial equity so often spun in history books. But my students’ anger is often more personal.

The students are not paranoid. The United States has a history of funding unethical studies on vulnerable populations. We read articles about similar cases in which U.S. doctors and scientists took advantage of vulnerable populations—from sterilizing female prisoners in California to infecting prisoners in Guatemala with syphilis.

It’s at this point that I ask students to write up their own code for bioethical human research: If you were in charge of how and what research could be conducted, what limitations would you place? How would you define informed consent? How would you guarantee informed consent? Is anyone off limits? If not, how do you guarantee that they are not being taken advantage of by unscrupulous researchers?

After writing their own codes, I distribute copies of the Nuremberg Code and the Belmont Report. The students then write a reflection on how their codes differ and what might be missing from each of the lists: How is your code similar to the Nuremberg Code and the Belmont Report? How is it different? What did you mention that should be added to those codes?

With their bioethical codes hung in the hallway leading to my classroom and armed with the knowledge that science isn’t always ethical, I give students their first major assignment of the year: a research paper on a bioethics topic of their choice.

Before we began this course with a study of the TSS, I read papers about artificially extending life or genetically modified creatures that sounded more like science fiction than real issues affecting my students and their families. But now that we begin with an exploration of bioethics rooted in the history of the TSS, the papers have become more interesting and personal. I still give the students a list of bioethics topics from the CDC website, but through conversations in class and students opening up about their own experiences, the topics have increased in relevance and student engagement. Now students write about why mortality rates of cancers are different for people of different races. They explore how U.S. scientists have engineered studies taking place in Latin America. One young woman wrote a history of gynecology in the United States, from unanesthetized surgeries of women who were enslaved through much more recent forced sterilizations of women of color. Another student wrote about medical experiments by Japanese doctors in Chinese prisoner of war camps during World War II. They now write about subjects that tomorrow’s doctors and researchers need to understand in order to combat the idea that the health and healthcare of some do not matter as much as that of others.

RESOURCES

Tuskegee Syphilis Study Mixer Materials [PDF]

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs): Syphilis. cdc.gov/std/syphilis.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. U.S. Public Health Service Syphilis Study at Tuskegee: The Tuskegee Timeline. cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm.

Tuskegee University. 2016. About the USPHS Syphilis Study.

tuskegee.edu/about_us/centers_of_excellence/bioethics_center/about_the_usphs_ syphilis_study.aspx.

Washington, Harriet. 2006. Medical Apartheid: The Dark History of Medical Experimentation on Black Americans from Colonial Times to the Present. First Anchor Books.