Mapping Childhood

How Our Stories Build Community

Illustrator: Simone Shin

This piece was adapted from the newly-released second edition of Reading, Writing, and Rising Up.

Narrative writing is the center of a social justice classroom. These snapshots from students’ lives build classroom community and connect their home worlds to the curriculum. Too often these days, though, testing and standards push narratives to the sidelines in favor of argumentative writing.

This drive to “just the facts, ma’am” teaching is wrongheaded on many levels. First, narrative is at the heart of all writing — stories, novels, and essays. Although David Coleman, architect of the Common Core, may believe that narrative writing is a waste of time, every good journalist, writer, politician, attorney, and teacher knows that stories matter. The Atlantic, Harper’s, and Yes! magazines certainly understand the pull of stories. When Michelle Alexander writes about prisons in The New Jim Crow (2012), she grounds her thesis in the lives of people caught in the web of an unjust legal system by opening her book with the story of Jarvious Cotton and his family. Ta-Nehisi Coates, in his award-winning article “The Case for Reparations,” portrays Clyde Ross’ search for a home in a corrupt housing market to propel understanding of how systemic racism has worked against African Americans. These stories bring humanity to a thesis, showing how abstract concepts like justice and inequality work on a human level.

The exclusion of narrative from the curriculum also silences students, erasing the political connections created by paralleling their own oppression, struggle, and joy to the curriculum and reading. Our students’ stories about their lives provide the bedrock my curriculum rests on. Like Alexander and Coates, I use the narratives written in my class to help students understand broader issues in society. Whether they are sharing stories of neighborhood games, musings about their experiences with inequality in education, tales of pranks gone wrong, or moving us to tears about injustices they have endured, their lives provide insights about contemporary society. When we reorient the curriculum toward justice, we must pair literary and social inquiry with examinations about how these events play out in our students’ worlds.

Over the years, my students have been a delightful blend of colors, sexual orientations, and genders, and have come from diverse economic statuses. They differ in the activities they enjoy: Some love football and basketball; some love ballet or African dance; others are into politics, hairstyling, or music. They differ in their home languages, access to wealth, healthcare, and housing. Sometimes those differences create a loving atmosphere and sometimes they create conflict. Because I want them to get comfortable talking across these lines at the beginning of the year, I take them back to their childhood to explore memories while they work on their narrative writing skills. Their laughter and tears over their shared experiences of toys, cartoons, books, recess rituals, games, even clothing, pain, loss, and shame contributes to creating a classroom community that later makes our difficult conversations about contemporary issues possible. These seemingly innocent childhood stories also carry lessons.

For some students, this comes easily and naturally, but for most students — and adults — I need to saturate them in stories and ground them in the past, helping students dig through their childhood recollections to find those moments from their lives that formed them. Nurturing strong writing means giving them time to explore before they put pencil to paper or fingers to keyboards. By reading examples from my former students, I convince them that their lives are full of stories, every bit as worthy of writing and sharing as published writers. Yes, most kids played hide-and-seek, but did they have the kid on their block who always broke the rules? Was there someone who found the best spots and hoarded them? Did they cheat and their sister told their mother and they got in trouble? How we tell our stories — the actions, the dialogue, the character descriptions — can merely entertain or can reveal the world that shaped us.

Stephenie Lincoln’s story “Neighborhood Hassle” describes Steph’s attempt to play basketball with the boys. On one level, it is the story of an episode in Stephenie’s neighborhood ball game. On another level, it is about the assumption that girls “can’t ball.”

I was always a tomboy, but I never let them know I could ball because they were so mean. But I was fed up. So I had decided it was time to school ’em.

It was my ball again. I dribbled to my left, crossed to my right, and busted a “J.”

“In yo face Timmy,” I said like I was all that. “My ball.” I went right, tried to go through my legs, and Timmy stripped me. He laid it up and the score was 2-1, me. His ball.

All the fellas was jumpin’ up and down now yellin’, “Go Timmy, don’t let no girl beat you.”

Stephenie’s triumph in the story teaches the boys a lesson. Through her retelling of the event, we learn about gender stereotypes and the importance of not giving in to other people’s perceptions about us. But we also learn about defiance and resistance.

In “My Name Is Not Kunta Kinte,” DeShawn Holden takes us to the berry patch to pick berries with his family, but from the time his mother wakes him until his grandmother admonishes him for “chucking” dirt clods and hitting her by mistake, we are in the world of a family: the sayings, the teasing, the sibling and cousin rivalry. And while I’m sure that DeShawn learned not to hit his grandmother with dirt clods, the larger lesson is about how these outings and rituals shaped his family.

Rushed by parents and siblings, I walked right out of the house with eye boogers still in the corners of my eyes and slobber stretching from my mouth to my ear. I didn’t care until my grandmother, Mrs. Rise and Shine herself, who goes to bed at 8 p.m. and starts her day at 3 a.m. said, “Boy, why haven’t you washed your face? You look like you been sleeping in a barn. And you didn’t even bother to comb yo’ ole nappy head. Looks like chickens been having their way with it.”

She meant well, even though it sounded pretty harsh. I love my grandmother. She was light in spirit, but heavy everywhere else. She was a strong woman, a warrior, and a survivor. My grandmother loved me in spite of all my mischievous, devilish, sneaky ways. She always managed to speak life when I was bad and everyone else wanted to speak death. She said that I was going to be the one to grow up to be a preacher.

DeShawn’s narrative demonstrates the importance of celebrating authentic storytelling, including “home language” and bringing into our classrooms stories and people who influenced us. Lessons from our lives should not be separated from the curriculum.

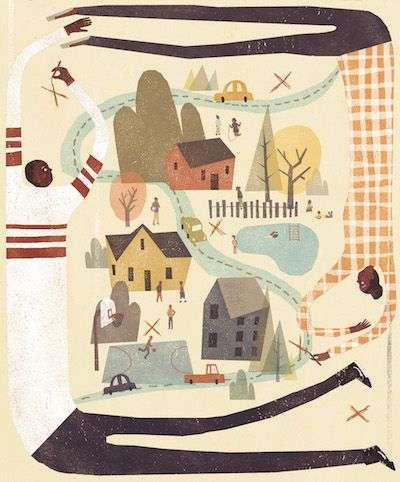

The neighborhood map is a standard, one that I learned from Vince and Patty Wixon and Kim Stafford when I went through the Oregon Writing Project in 1980. This narrative prompt uses students’ lives as the material for the writing; it incorporates reading, drawing, and talking so students have multiple opportunities to collect their memories and practice telling their story before they begin writing.

Drawing and Modeling

To begin the lesson, I draw a map of one of the neighborhoods where I grew up — K Street in Eureka, California — on the board or document camera. As I draw, I label streets and neighbors’ houses on my map. I put an X in the backyard and tell the story of the time my sister Tina got me to play dentist, tied me to a chair, and tried to take my teeth out with our father’s rusty pliers. I can still taste the rust when I tell the story. I put another X by the big hill going down to Susan Runner’s house, and I talk about the time my brother Billy built a go-cart and pushed me down the hill before teaching me how to use the brakes. Both of these stories highlight lessons I learned — beyond my siblings putting my life in danger — of weighing fun and danger against boundaries. As I draw and tell stories, I point out the importance of specific details like names and descriptions that help build the narrative. I don’t go on too long — long enough for them to get the idea, but too long and I lose them.

Because I also want students to surface and critique fundamental aspects of our society, I also extend my map to include my high school. I place an X by Mrs. Harper’s room. I tell about the day she humiliated me for “talking wrong” and made me stand in front of the class and pronounce words and conjugate verbs. I also place an X by Mrs. Johanson’s room. This teacher pushed me to join the debate team and spar with Daniel Chin about the draft and alternative service during the war in Vietnam. Instead of shaming me, she transformed me by making me see myself as capable instead of inferior. There’s an X for the day I demanded that girls be allowed to wear pants to school. My efforts failed, but the incident provided an understanding that I need to work for change when I experience oppression.

The stories I model help students surface memories they might want to write along a scale of safe to risky. When I risk sharing times I experienced pain as well as transformation, the classroom becomes a crucible where students’ collective stories forge insights into our society, probe the fundamental inequalities that limit us and move us to seek justice — as well as laughter. Teachers who work in places where kids have tough lives sometimes resist asking them to write about their lives because they have encountered tragedy. But they have also encountered joy as the poet Nikki Giovanni reminds us in her great poem “Nikki-Rosa”:

Black love is Black wealth and they’ll

probably talk about my hard childhood

and never understand that

all the while I was quite happy

I hand out crayons and legal size paper and ask students to draw a map of a neighborhood they lived in that they want to write about. Some students have moved a lot. Some are houseless. I tell them, “Some of you moved a lot and might have fewer memories from one place. Some people who have only lived in one place might not have as many stories as you do exploring new territory. You can make multiple maps. There’s no way to be wrong. You can also use the school as a neighborhood like I did.” Also, I tell them this is a messy map. They don’t have to worry about it being correct or perfect. They just want to get down street names, neighbor names, nicknames of places like “spider tree,” and place an X where incidents happened that they might want to write about.

After students have created their maps, I ask them to find a partner. “You are going to take turns telling stories. First, one of you will be the storyteller while your partner is the listener. Then you will switch. Tell about the places where you marked an X, just like I did. Listeners, I want you to help the writer by asking questions: What else do you want to know? What other details would help you see this story? Draw the writer out. Also, notice if their stories remind you of something you can add to your map.” Because some students take longer to come to stories, this partner share helps stimulate ideas. Telling the story is a rehearsal for the writing. While the drawing helps locate the story, talking helps the writer recall more details. Once partners have discussed their maps and stories, I ask for a few volunteers to share from their map. Before they speak, I tell the class, “Listen to these stories because they might trigger a new memory for you.”

Let me pause to say there are always students who have a tough time finding a story, but this narrative offers multiple points for students to raise up memories: First with the mentor texts, next with my map and stories, next by drawing, and then again by partner sharing. Drawing the maps, especially in silence, functions as a meditation that allows students to travel back in time and recreate memories.

Reading the Models

Once students have located their own stories, I distribute “Super Soaker War” by Bobby Bowden. I start with this piece because most students can relate to taking play a little too far and getting in trouble. I read the story “with attitude” as students read along silently. Then I ask students to read it again on their own and make marginal notes: What do they like, what questions do they have, what reminds them of their own life? How does the writer bring the story to life? We discuss their observations, but also listen as their own stories of getting in trouble bubble up after hearing Bobby’s story.

If they point out his character or setting descriptions, I might add that describing characters is a good way to make their writing come alive. If they don’t notice the dialogue, I will notice it for them. While I don’t over-teach the craft of narrative writing at this point, students need to understand that elements like description and dialogue move their piece from a one-sentence summary — Bobby got in trouble for putting paint in super soakers instead of water — to a story. We read Stephenie Lincoln’s and DeShawn Holden’s stories so students see how different people approached the same writing assignment, to develop “story sense.” The models help writers hurtle into their storytelling without worrying about whether they have all of the elements or got it “right.”

Guided Visualization

I frequently take students on a guided visualization before they start writing. The visualization provides a quiet pathway from the chaos of churning up stories to the quiet zone of writing. They read over their list and circle one childhood memory they want to write about. I close the blinds, turn out the lights, ask them to get comfortable, and close their eyes. (I joke around as I do this. “I promise no one will look at you. Put your head on the desk if you think they might.” I exaggerate taking big breaths, rolling my shoulders. . .) I pause about 40 seconds between each question so they can raise the memory. I typically take them through setting, character, and then put the story in motion. I say, “Remember the event. Imagine the room or playground or park where the memory took place. What does it look like? What does it smell like? What sounds do you remember? Who else was there? What did they say?” There are no set questions for these visualizations, but I try to get students to see, hear, smell, taste the memory — to create a movie in their heads of the childhood memory so their writing will be more detailed. If they can’t recall exactly what someone said, I tell them to make up something that fits their memory of the event.

To transition from the guided visualization to the writing, I tell students that when I turn on the lights I want them to write as fast as they can because sometimes they will capture memories they might otherwise forget. This is a first draft. I also say, “Write this as if you were talking to a friend. Tell the story. Don’t be afraid of making mistakes. Everything can be cleaned up in revision.” Students start writing in class and finish the draft at home.

Read-Around and Collective Text

As students write, I circle the room and a few push their drafts to the edge of their desks inviting me to look at their papers. I “read” the room. If I see that the majority of students are on track, I move ahead with a read-around. If a number of students seem stuck, I might encourage a few who “got it” to share their drafts so that their classmates can push off from their models. If more seem stuck than unstuck, I will move into some revision strategies to teach them how to build a stronger story.

Before we begin the read-around, I tell students that they must take notes on their classmates’ stories. Certainly I want them to think about what they like in the piece, including use of language, dialogue, description, and evocative details that help them “see” the story. The read-around provides one of the best teaching tools as we collectively figure out why Tara’s story “works” or how the details of dialogue created DeShawn’s grandmother as a woman we want in our lives. Students learn writing techniques from each other: how to use dialogue or blocking, how to use metaphor as a tool for character description. As each student reads their paper, the rest of the class takes notes. After the “writer” finishes, we applaud, then give specific feedback about what “worked” in the piece. I begin part of the read-around by saying, “We all need to learn what we are doing right so we can keep using that tool. We also want to keep everyone writing. Give the writer some love. Also think about what we learn about society from this piece.”

But the read-around provides another vital function in a social justice classroom — the connection between students’ lives and the world — in the way that Alexander’s and Coates’ stories illuminated the justice system and housing inequality. Bill Bigelow, my teaching partner and husband, coined the term “collective text” to describe these post-writing discussions. Instead of just applauding the pretty phrases or hilarious stories or even noting the technical prowess, which is important, we also want to probe the lessons these stories teach us about our childhood: what we learned to fear, how we learned to treat others, how parents taught boundaries or consequences on our way to adulthood.

Yes, we must teach students to write narratives in this time when their stories are dismissed as irrelevant or unimportant or impractical in the world of work. But we must also teach them to listen to other people’s stories, to learn lessons from Stephenie’s refusal to be sidelined by gender expectations, to celebrate a home that teaches the value of communal work, or to remember that there are consequences for destroying other people’s property. In a social justice classroom, every lesson must build toward a more just, inclusive society, including the seemingly innocent stories of our childhood.