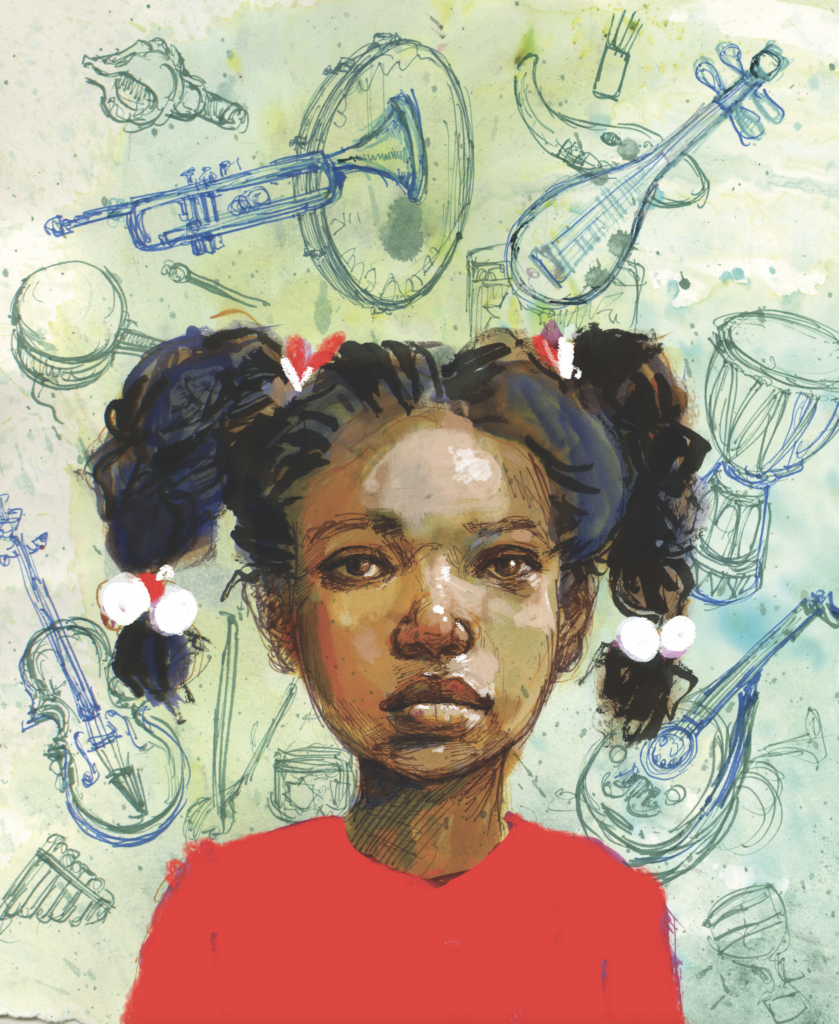

Listening Between the Lines

The Sound of Curriculum

Illustrator: Molly Crabapple

Neema’s mother wanted to meet with me.

Neema was a happy, well-mannered 4th grader with big bright eyes who seemed ready to learn. She was a bit shy, but she seemed happy to come to music class. When her mother requested a conference, I immediately became worried. Had I missed something? Bullying, teasing, or something worse?

New to the school, I wondered if the problem was my teaching style. I had previously taught in a largely affluent white community. In contrast, this school is racially diverse with about 60 percent of students qualifying for free and reduced lunch. Some students’ families have immigrated to the United States. My previous experience with first-generation students had been limited. My experience with their parents was even less. I had been trained in culturally responsive teaching and was working as an equity liaison. I filled the curriculum with music from diverse genres and cultures to promote inclusivity. Growing up, I was the Baptist student at the private Lutheran school. As an adult, I was often the only African American in predominantly white settings. Knowing what it felt like to be the “other,” I worked hard to ensure that all of my students saw mirrors and not just windows in the classroom. What could I have done wrong? Reluctantly I made an appointment to speak with Neema’s mother. Now all I had to do was wait. And worry.

Before the meeting, I mapped out all of the things that I would say. I followed the checklist provided for conferencing with parents: Say something positive about the student, give an anecdote about the student’s behavior in class, discuss one area for improvement, then finish with a hopeful statement about the future. I was ready.

When Neema’s mother arrived after school to see me, she was wearing a blue head covering. Unsure how to greet her, and not wanting to offend, I smiled and gestured for her to take a seat. Although she had requested the meeting, she did not immediately begin the conversation. Uncomfortable with the silence, I began to tell her about Neema’s accomplishments in class. I discussed her helpfulness, and how she always answered questions when I called on her. I mentioned her shyness when we sang and danced but added that she always tried. Neema’s mother did not respond. I realized that she had never looked me directly in the eye when I was speaking. I finished by saying that Neema was a wonderful student who I enjoyed having in class. Then she said, “That’s what I wanted to talk to you about. I don’t want my daughter to take this class anymore.”

I was confused. Why didn’t Neema’s mother look pleased? Her daughter was happy and doing well. Isn’t this what all parents want? Slowly she went on to tell me that she had noticed changes in Neema’s behavior at home. She was singing little songs and dancing when she thought that no one was watching. I was still struggling to find the problem. Neema’s mother looked at me and said, “That behavior is not allowed in our culture.”

What behavior? What had I done? I had always tried to be respectful of families and culture. I carefully chose the music that students listened to and performed. Images on my walls were representative of the musicians around the world. I used movement activities, not dances, and no one was ever forced to move if they were uncomfortable doing so. There were thousands of thoughts in my head, yet I could think of nothing to say.

I realized that I knew very little about Neema. What was her family’s culture? What were their religious beliefs? I had heard her speak English. Did she also speak other languages? What language did she speak at home? Though I said nothing, my confusion must have shown on my face. Silence once again filled the room but this time it was Neema’s mother who filled it, explaining the beliefs of her family. They were practicing Muslims from Somalia. Their family believed music and dance were to be used only during worship. They were not for recreational purposes.

Oddly, my first thought was denial. Some other Muslim students’ families seemed to support their child’s participation in music class. She couldn’t possibly mean that they listened to no music. Everyone listened to music. My first memories involved music, including standing on a bed and conducting the “Hallelujah” chorus on Easter. I couldn’t imagine how someone could even exist without music. My life had an accompanying soundtrack — Glenn Miller, go-go — that played in my head constantly adding new songs, sounds, and rhythms as I was introduced to them. In my mind, there were two types of people: people who created music and people who consumed music.

I felt myself begin to get angry. I looked at her in amazement. Shifting in my chair, I knew that I couldn’t let myself speak until I was able to control myself so I folded my arms. Neema’s mother sat still. Finally, I broke the gaze and looked away, allowing my self-righteous indignation at her statement to grow and fuel my anger. Music was not something that could just be dismissed. I worked hard to provide my students with a good education. Not only a good music education. Music has been used throughout history to convey joy and pain, to celebrate and commemorate, to chronicle events and to protest against societal wrongs. My classroom was a place of inquiry and exploration. Besides, what was I supposed to do? This was not my problem. Music was a part of the prescribed curriculum. Did she really expect me to change what I taught because of her beliefs?

Patiently, I explained that music was more than performance. I recited some of the intangibles gained from studying music relating to the five C’s of education: collaboration, communication, creativity, critical, and computational thinking. She slowly shook her head and said, “Neema is not allowed to participate in music.” The discussion seemed to be over. Standing up, I thanked her for coming in with assurances that I would discuss her concerns with my supervisors.

I immediately contacted the administrators in my building, and the music supervisor for the district. I had gone as far as I could. Neema was in the 4th grade, she had been in music class since kindergarten. No administrator could see me until the next day. My supervisor said that we could talk at our monthly meeting. That was more than a week away. I needed an answer now.

When I spoke with my principal the next day, I was told, “It’s a required course. She has to take it unless there is an IEP or 504 plan exempting her.” Once again, I felt that I was being dismissed. I had Neema’s class two days later. With no support or plan, I had the students do theory worksheets. No singing. No moving. No playing instruments.

The music meeting the following week allowed me a chance to speak with Neema’s teacher from the previous year. The teacher had accepted a position in a middle school, which opened up the position that I was now in. Before I could speak to her alone, our supervisor began the meeting and brought my question to the group. The situation was explained without identifying me or my student. There was silence at first. Although I couldn’t see faces, I could see the body language. There was shifting in seats, moving of heads, and folding of arms. A hand went up and I realized that it was the teacher who I had wanted to speak with. She said that she had a similar situation at a previous school. She laughed a little and said that she let the child go to the library during music. Someone else asked what she did about her grade. The teacher replied, “I passed her. Barely. She wasn’t doing music. It wasn’t my fault. I was teaching.”

This opened the floodgates. Suddenly, the tone changed in the room. I started to hear other teachers mumble about the curriculum, change, and fairness. A teacher who I had worked with for years said, “This curriculum has worked for hundreds of years. They came here for education. This is our curriculum. If it was good enough for Beethoven, then it is good enough for them.”

They? Them? Had it really come to this? I wondered when the conversation had changed. This was not what I had expected. I had wanted help to solve a problem. A problem that I thought was important. A problem that a parent thought was important. But was it important to us for the same reasons? How had I looked to Neema’s mother? Did she notice me shifting in my seat, moving my head, or folding my arms? My colleagues’ responses upset me. Yet they were the same responses that I had given to Neema’s mother. The group soon moved on to other topics. However, I couldn’t stop thinking about what I had seen and heard. Nor could I stop thinking about my own behavior. There were two things that I learned at this meeting. First, I needed to get help. Second, I was not going to get help from the school system.

I went to the library to look for information and mentioned the situation to the librarian. The librarian told me that she allowed Neema to come to the library the previous year because she understood Neema’s situation. When she was a child, she wasn’t allowed to listen to “worldly music.” She had grown up in West Virginia in a strict Baptist environment. Since there were other students in her community who also couldn’t listen to music, she said that it “wasn’t so bad.” The group sat outside the room in the hallway during music.

Until that moment it had never occurred to me that there might be other students who were in the same situation as Neema. For most students, including some who identified as Muslim, there was no apparent conflict. Music and movement, within boundaries, were perfectly acceptable. However, now I could see how some students might face a difficult situation every time they entered the music room. It frustrated me. It also made me more determined to find a way to make the system work for all students. I could do the work on the inside of the system, but I knew that I needed an ally on the outside.

I placed the call hoping to leave a voicemail, but Neema’s mother picked up the phone on the third ring. We greeted each other and I began the conversation by apologizing to her for my behavior during our last meeting. Soon words were spilling out of my mouth about curriculum and teaching and music — jumbled together with no rhyme or reason. My feelings. My problems. Once again, it had become all about me. As if reading my mind, Neema’s mother replied, “I understand your problem. I want to thank you for being concerned about Neema.”

Just when I thought that we were headed toward another awkward silence, she asked the question that I had been waiting for someone to ask me since our first conversation: “How can I help you?”

Hoping that I wouldn’t offend her, I asked if she would share her beliefs on music. She told me that music was an important part of her family’s spiritual life. In fact, that was what made it sacred. Music was one of the highest forms of praise, it was to be an offering, a gift. It was not something that was to be used as a game, or for dancing. Words, spoken or sung, were important.

For the first time, I didn’t just hear her words, I listened to them. She was not dismissing music as frivolous and unimportant. She was not disrespecting my feelings, my job, or me. I had been making this all about me. Wrapped up in my own feelings, I had forgotten that there was a child. A child caught between two worlds, having to choose between the values of home and the requirements of school. That was a choice that no child should have to make. I was the teacher. It was up to me to help my student succeed. I thanked Neema’s mother and told her that I would get back to her with a plan.

Armed with my two favorite tools, colored sticky notes and highlighters, I examined the music curriculum for non-performing standards. To my surprise, most of the standards were non-performing. I checked the internet for activities and resources that I could use. I started with books and found The Wheels on the Tuk Tuk. I wondered if it was similar to the song “The Wheels on the Bus.” My first instinct was to sing both songs and compare and contrast them with students. Instead, I created a lesson that would be accessible to Neema — comparing and contrasting the lyrics. This led to a lesson on the instruments of India and the instruments of the United States. Additional book recommendations popped up on my Google search, including Ada’s Violin, which described how children in Paraguay played instruments that were constructed from recycled materials. In my mind I began to see all kinds of instruments that could be constructed from recycled materials.

Project-based learning was not something that I had explored a great deal in music, but that didn’t mean that it couldn’t be done. Within a few hours I put together a draft of a standards-based music choice board built around the non-performing aspects of music. Math activities. Science activities. Career opportunities in music. Providing a choice board would give students autonomy to choose. It also meant that Neema would not be singled out. Perhaps it would open up an opportunity to participate for other students who hadn’t spoken with me. There could be puzzles, games, coloring activities, reading, singing, and playing options. I emailed Neema’s mother a copy of the choice board and called to explain my plan. She made suggestions on things that I could include when introducing percussion instruments, such as a daf, which is a large Persian frame drum. No longer was this parent looking at her daughter’s music program through a window, she was helping to build a mirror.

With that in mind, I made adjustments to the traditional end-of-year concert format. I planned a music showcase instead. Students could present traditional performance activities in the auditorium. or present music-related projects, papers, and pictures on non-performing aspects of music in the atrium. It was in that area, that I could see Neema and a friend happily explaining the life of a composer to a group of people. I could also see her mother and though we spoke not a word, I could see in her eyes, a smile.

Neema and her mother reminded me of something that I had forgotten. A curriculum should be a living, breathing document. It should be examined and revised to meet students’ needs.

There is a wonderful line from a song that says “If you become a teacher, by your pupils you’ll be taught.” As educators working with culturally and linguistically diverse children and families, we must be willing to reach out of our own comfort zones and listen to our students and their families. We must see families as partners. We must not only hear them but listen to them and work with them.