Classrooms of Hope and Critique

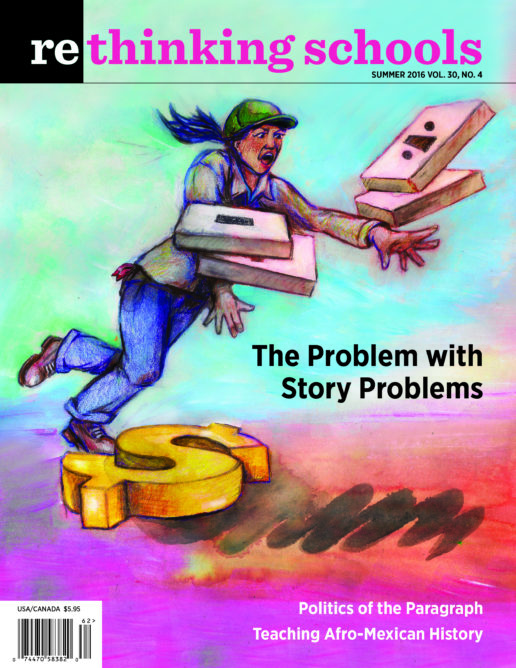

Illustrator: Barbara Miner

In the introduction to our book Rethinking Our Classrooms, we quote the late, great Brazilian educator Paulo Freire, who urged teachers to “live part of their dreams within their educational space.” We added: “Classrooms can be places of hope, where students and teachers gain glimpses of the kind of society we could live in, and where students learn the academic and critical skills needed to make it a reality.”

In an era of high-stakes testing—not to mention war, xenophobia, racist violence, climate chaos, and growing inequality—such an aspiration can seem wildly romantic. Until we realize that teachers everywhere are doing just that: nurturing classrooms of hope and critique.

Articles in this summer issue are glimpses into the classrooms of educators who are teaching for social justice, defying the notion that schooling should be reduced to test preparation and the training of “successful” workers.

Our cover article, “The Problem with Story Problems,” is from teacher educator Anita Bright, who uncovers troubling biases embedded in story problems in math textbooks—from elementary through high school levels. Bright shows how seemingly neutral math problems are anything but. Instead, they often reinforce racial and gender stereotypes, encourage students to imagine themselves as bosses, reduce workers to sources of profit, and promote consumerism and the acquisition of “stuff.” But Bright also describes how teachers are helping their students think critically about these word problems and repurpose them with more humane and ecological values. Math teachers, she writes, can “create a classroom climate where challenging the status quo is accepted, normal, and encouraged.”

Language arts teacher Michelle Kenney describes how “top-down mandates from the state, private testing corporations, federally funded grants, and pressure from the media gradually chipped away at teacher autonomy” in her district, and led teachers at her school to adopt a formulaic writing program. She laments that writing for her students became a series of hoops to jump through. Her article is a defense of teacher knowledge and student creativity, of critical thinking and questioning the world.

Wendy Harris works with Deaf students in Minnesota. She discovered that educators in the late 19th and early 20th centuries discriminated against Native American and Deaf students in similar ways. While institutions like the Carlisle Indian Industrial School tried to “kill the Indian and save the man,” “experts” in Deaf education like Alexander Graham Bell aimed to weed out a “defective race of human beings”—Deaf people and Deaf culture. Harris decided to put this juxtaposition at the center of her curriculum. She helps students recognize that the “removal of culture and identity, often by violence, [offers] a connection between the experiences of Native Americans and Deaf people.” She also encourages students to focus on how Native Americans and Deaf people could—and did—resist cultural genocide. As Harris shows how she nurtures her students’ Deafhood, she expands our thinking about culturally relevant pedagogy.

Michelle Nicola remembers when one of her students blurted out in class: “Wait, Señorita! There are Black people who speak Spanish?” In “Rethinking Identity: Afro-Mexican History,” she describes the unit she developed for her Spanish heritage students to uncover the hidden history of “how enslaved Africans and their descendents have shaped Mexican culture.” She takes us on a people’s history excursion that shows the joy and revelations that emerge when a class peers beneath surface understandings: “African slaves were singing ‘La Bamba’ in 1683!”

The new report from the Southern Poverty Law Center, “The Trump Effect,” about the impact of the 2016 presidential race on our students, concludes: “The campaign is producing an alarming level of fear and anxiety among children of color and inflaming racial and ethnic tensions in the classroom.” In this context of immigrant- and Muslim-bashing, British Columbia teacher Nassim Elbardouh describes the very different Western responses to last fall’s bombings in Paris and Beirut, and the impact on her, her family, and her students. Elbardouh, whose family comes from Lebanon, describes the harm she has seen wreaked by Islamophobia and a broader, underlying set of assumptions about whose lives matter the most. She argues that we must not leave students to fend for themselves and shares valuable resources for teachers who want to engage their students in looking at these issues.

Finally, in his poignant “A Teacher’s Letter to His Future Baby,” Greg Huntington reminds us that all childrearing—and all teaching—anticipates a particular kind of world. He opens with a quote from John Dewey: “What the best and wisest parent wants for his child, that must we want for all the children of the community. Anything less is unlovely, and if left unchecked, destroys our democracy.” Huntington’s letter sings with his hope for his child and for the world that his child will help create. His words to his new baby remind us that at the core of all our work with children—and all our work to rethink and defend public schools—is love. Love and hope.