Let’s Stop Using Metaphors that Celebrate Extraction, Colonialism, and Violence

Earth, Justice, and Our Classrooms

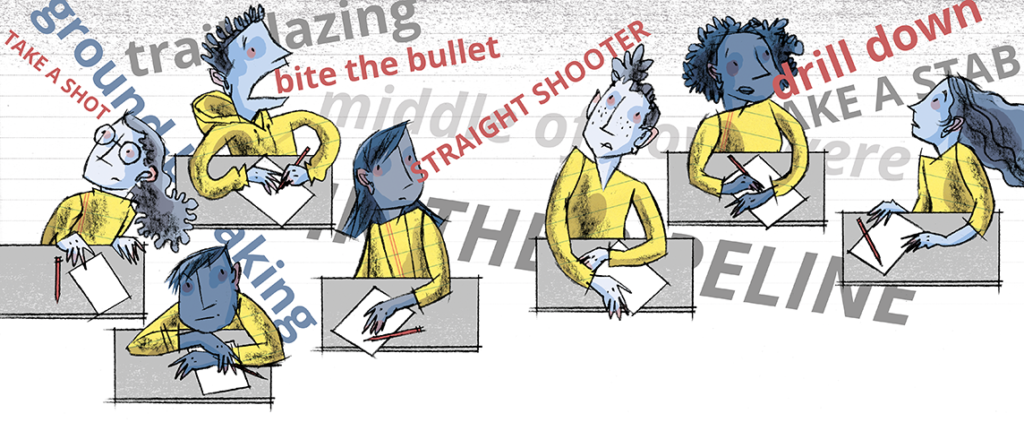

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

The language we use every day — both inside and outside the classroom — is metaphor-rich. We use images drawn from our lives to illustrate other aspects of life.

Metaphors bring nuance, aural beauty, and poetry to our language. Think, for example, of Zora Neale Hurston’s “I have been in Sorrow’s kitchen and licked out all the pots.”

However, too often our metaphors embed messages that are hostile to the Earth and to social justice. Metaphors can reflect — and legitimate — a violent, extractive, colonial worldview.

Some problematic metaphors are so ubiquitous as to be virtually invisible. After the horrific shooting at the Tops Friendly Market grocery store in Buffalo on May 14, 2022, killing 10 shoppers and employees, a Washington Post headline announced “Buffalo’s East Side was a food desert. The shooting made things worse.”

Food desert. It’s a term I’ve used myself to describe how poor communities, usually communities of color, suffer from scarce availability of nutritious, affordable food. But listening to the “The Desert” episode of the excellent podcast As She Rises made me realize what a harmful metaphor it is, because it paints a mental picture of the desert as a place of gray emptiness. (See Tim Swinehart’s article “As She Rises” in the spring 2022 issue of Rethinking Schools.) As Navajo Nation Poet Laureate Laura Tohe explains in the podcast, “People have these assumptions that just because it is a desert there is nothing there — and it is not important.” And if a place is empty and unimportant, then that is a perfect place to designate an “energy sacrifice zone,” as the Nixon administration did, and to allow corporations in to dig and scrape and drill. But the desert teems with plant and animal life and is home to Indigenous Pueblo and Navajo people — “I am dressed with the beauty of the land,” says Tohe.

So let’s stop using “food deserts” to describe places where people suffer from limited availability of food choices. It’s a metaphor that numbs us to the violence of mining and fracking in places like Arizona and New Mexico, where, thanks to extractive practices, rural air pollution matches that in cities like Houston and Los Angeles. As Tohe says, “It is another kind of genocide.” Our metaphors should not offer linguistic cover to genocide.

And while we are at it, let’s shed “wasteland,” a term, like desert, that allows for the possibility of a land so devoid of value that it can be abused in whatever manner is at hand. Its companion expression, “in the middle of nowhere,” heaps contempt on any place that is not of supposed substance — unlike, presumably, major urban areas, where people who matter live — and similarly invites exploiters to have at it. Nobody cares about Nowhere.

Once I started to pay attention, I became aware of how much of our language draws on and reinforces an extractive worldview. How many meetings have I been in when someone said that we should “drill down on that” — equating drilling into the Earth with learning more about a subject, teasing out implications. We talk about “prospecting for proposals,” a “rich vein of investigation,” a “rich lode of ideas,” to “mine that topic,” a “gem of a person”; it was a good idea, but “it didn’t pan out.” Something that is brilliant, wonderful, is a “gold mine,” “worth its weight in gold”; the best of a category is the “gold standard”; and, of course, prizes are awarded in terms of metals dug from the earth: gold, silver, bronze, an alloy of copper and tin. The New York Times quoted a Milwaukee broadcaster who said that “the team concept and strategy are all things we should be mining from an entertainment perspective.” Our language should stop borrowing imagery from the ripping up of the Earth. Extraction should not be glorified.

“Pipeline” deserves special mention, as it is one of the most-used metaphors in the English language. “In the pipeline” yields more than 40 million Google hits. Derek Lowe has a Science magazine blog, “In the Pipeline,” about the pharmaceutical industry. A magazine editor asks, “Do we have enough articles in the pipeline?” Sure, not everything in a literal pipeline is toxic fossil fuel, but a fossil fuel-powered world is inconceivable without our furious tangle of pipelines, and employed as a metaphor, pipeline is obnoxious and paints a benign portrait of something that puts at risk all life on Earth.

Think about the problematic use of “pipeline” in a report from the Harvard Graduate School of Education: “We had discovered in our foundation work the need to catch students as they [fell] out of a very leaky [school] pipeline, making sure that they transitioned from 6th to 9th grade.” In this metaphor, students are regarded as a commodity moving from place to place, with no initiative, no agency of their own. Being concerned with middle school students is admirable; regarding schools as pipelines is not. An article in the Oregonian about Oregon dropping the college requirement for substitute teachers included this line: “Anthony Rosilez, executive director of the state’s licensing board, hopes this will create a pipeline of substitute teachers from school districts’ communities.” The pipeline metaphor shapes how we think about the issue being described: a thing in a conduit — the same at one end as it is at the other, an object without initiative or consciousness.

Our language is filled with metaphors rooted in extraction. And extraction and colonialism go hand in hand. One of the most-used words during the early days of the pandemic was “uncharted.” But uncharted is a metaphor with imperial undertones, along with, of course, “plant the flag.” Uncharted implies that something is not really known until it is surveyed and mapped. In this worldview, the Colorado River was not known until charted by the white expedition led by John Wesley Powell. No matter that the river was known, used, and loved by Indigenous people for millennia. As described at the U.S. Department of Interior’s website, Powell led “a journey that would cover almost 1,000 miles through uncharted canyons and change the West forever.” Charting is prologue to changing the land to accommodate the interests of the invaders.

Recently, I found myself paying tribute to the Zinn Education Project’s “groundbreaking report” on Reconstruction — my words — as if ground needs to be broken to be made better, “developed” before it can take on significance. We say that someone does “trailblazing” work when it is new, original, and important — trailblazing, as enacted, for example, by the imperial pioneers on the Oregon Trail.

And “pioneer,” itself, is a metaphor that has similarly become synonymous with doing something novel, something that matters. Pioneering work is exemplary, maybe a bit daring. But its metaphorical lineage begins with colonization: white people moving into Indigenous people’s land — the “pioneers” in Laura Ingalls Wilder’s racist Little House on the Prairie series, or Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett. The word itself comes from the Middle French word pionnier, or foot soldier who makes roads, dig trenches, builds bridges as the military advances.

In 1992, I was in a workshop led by Rethinking Schools editor Bob Peterson. When participants used the expression “butcher paper,” Bob, a lifelong vegetarian, changed it to “chart paper.” It took me a while to grasp the distinction, but once one begins to pay attention, it is hard not to recognize the (environmentally unsustainable) meat metaphors that litter our language. Wendy’s “Where’s the beef?” ad was used famously in a 1984 presidential debate by Walter Mondale to mock Gary Hart’s “new ideas.” Beef and meat have been used as inappropriate synonyms for “substance” seemingly forever: Can you beef that up? That session wasn’t meaty enough. Even an article on the Coronavirus in the venerable socialist journal Monthly Review repeated the metaphor: “The deadliness of any potential pandemic strain is the meat of the matter, of course.”

And extractive, colonial, Earth-unfriendly metaphors inevitably are accompanied by metaphors of violence. Listen for how many times in a day you hear “I’ll take a stab at that” or some variation: I’m shooting to have that done by next week. Sure, I’ll take a shot. Bite the bullet. A straight shooter. Pull the trigger — as in “seal the deal.” No telling what that could trigger. And the hoary: Kill two birds with one stone.

No. Metaphors are not actual violence, actual colonialism, actual destruction of the Earth. And yet, the imagery of our language is not harmless either. These word pictures reflect the world we live in, but they also confine our imaginations to what exists. And our metaphorical language can justify the unjustifiable. Every time someone says, “Let’s drill down on that,” it offers support for the worldview of those who are not just metaphorically, but in reality, drilling down on that: the frackers, the Arctic exploiters, the water polluters.

Becoming more conscious of the metaphors we use to describe the world can help us to picture a different one. Instead of killing two birds with one stone, we can feed two birds with one hand. We can have streams or rivers instead of pipelines. My wife Linda Christensen has taught the metaphorical verb sister to our 5-year-old grandson Mateo. Sister is a construction verb, describing two boards brought together to make the whole stronger. It is a lovely metaphor of solidarity, of strength in numbers, and when Mateo now goes in search of a Magna-Tile to make his edifice stronger, he says that he is “looking for a sister.”

We can use our language to try to picture the movements we want to build, the people we want to become, the world we want to live in.