Lessons in Social Justice Unionism

An interview with Chicago Teachers Union President Karen Lewis

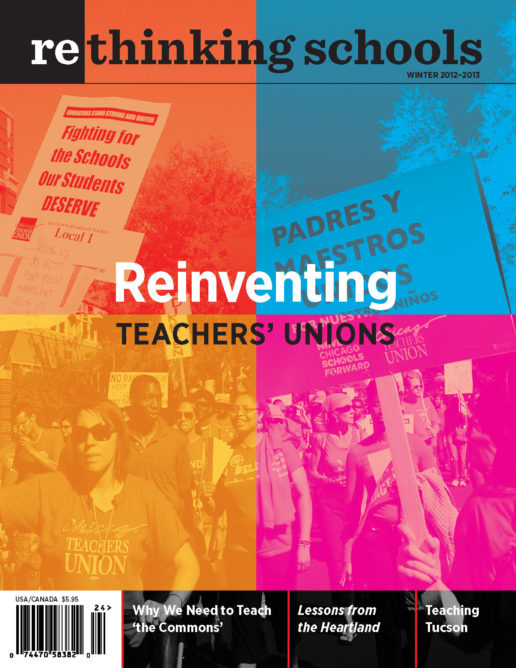

Illustrator: Chicago Teachers Union

Four years ago, Karen Lewis was a chemistry teacher, one of eight Chicago teachers who formed the Caucus of Rank-and-File Educators (CORE) to fight school closings (see “A Cauldron of Opposition in Duncan’s Hometown: Rank-and-File Teachers Score Huge Victory”). This September, as president of a transformed, democratic Chicago Teachers Union (CTU), she led the 30,000-member union in a successful strike in the city that has been a launch pad for the neoliberal education strategy. The collective and collaborative nature of the teachers’ union, and the breadth of parental, student, and community support for the strike, make understanding the CTU’s perspective and strategy critical for all of us interested in social justice unionism.

Jody Sokolower for RS: Set the scene for us: What were the issues that led to the Chicago teachers’ strike this fall?

Karen Lewis: The strike was a result of 15 to 25 years of anger about being blamed for conditions that are beyond our control. That’s part of it. The other part was a clear rebuke to the mayor and his friends about the top-down “reform” agenda and how it absolutely does not address the needs in the schools.

As soon as Rahm Emanuel [President Obama’s former chief of staff] came to town to run for mayor, he had as his education advisor the head of a charter school network, Juan Rangel. We knew from the very beginning this was going to be an ugly, bitter fight. Once Emanuel won the primary, before the general election, he was already heavily dabbling in Springfield and insisting that we not have the right to strike. Working hand in hand with Jonah Edelman from what I call “Stand on Children” [Stand for Children], he tried to raise the bar so high that we would have our right to strike theoretically, but wouldn’t have it in reality. They got legislation passed that meant we need 75 percent of our entire membership—not our voting membership—to authorize a strike.

Our membership was incensed; this was a law carved out just for Chicago. My response was: “Brothers and sisters, if we don’t have 75 percent of our members in favor of a strike, we shouldn’t strike. A strike is not something you do lightly.” Then we spent more than a year talking to members about the contract, getting them involved in the contract fight, getting their wishes and desires as part of the proposal that we presented to the board.

Once he was elected, Emanuel was so enamored of a longer school day that last year—in the middle of our contract—he went directly to schools to ask them to take a waiver and do the longer school day with no additional compensation, trying to bribe principals with $150,000 per school and teachers with free iPads. We had to go to the Education Labor Relations Board to enjoin them from doing that. Emanuel got 13 waivers before we clamped that down. That’s what happens when you have people running the school system who come from the business world. They think they can do whatever they want and do not understand how to deal with labor.

While parents liked the longer day, they also thought we should be compensated for it. They didn’t like the idea of forcing people to work longer without being paid for it. Parents are very clear about if you work, you get paid.

And the entire time, we were having conversations with our parents about what would make school better; we always had a different vision of what school should look like. We said, “You have the right to a longer day, but let’s make it a better day, because if you’re only elongating the day we have, everyone’s just going to get tired. There’s no evidence that a longer day in itself is better.” Parents wanted art, music, PE, world languages. They wanted classes that were not just reading and math all day long.

The parents understood that the mayor was bullying us. Parents also understood that we were being blamed and attacked for stuff that had nothing to do with how we managed our schools. They were clear about that. We have overwhelming support from parents whose children actually go to Chicago public schools. Sometimes when they do polls and ask parents, those parents don’t have kids in the schools.

Emanuel also took away the 4 percent raise that was already in our contract. What he really wanted was for us to open up the contract and go on strike last year so he could have imposed the longer school day. But we were adamant: We have a contract, we expect you to follow that contract.

JS: Because you wanted the extra time to organize?

KL: Absolutely. Had to have it. We were not mobilized, we were not organized, we were not ready. We needed the extra time to organize, but also to plan for the better day.

In the past, union leadership always said, “Save your money, we might go on strike.” But that’s not how you get people ready to strike.

We did not want to strike. I assumed that Emanuel would do everything he could to settle it before we had a strike. I was very wrong about that. We had a lot of pressure not to strike from politicians and advocacy organizations. But all along, we were very open about what we were going to do and how we were going to achieve it.

Building for the Strike

JS: When did you realize that you might need to strike?

KL: About when we announced it.

JS: You thought they would settle?

KL: I knew they would settle because they said they wanted to. Finally I said, “Well, I guess you don’t want to enough.”

JS: They thought you would cave.

KL: Yes, I think they actually did.

JS: How did you prepare for the strike?

KL: We had a timeline based on the new law and we backwards mapped based on what we would need to do if we were going to strike in September. We wanted to be prepared for it. Most unions aren’t prepared for a strike. It’s more a threat than a reality.

We created contract action committees in every school. We created an organizing department; our union never had an organizing department. We created a research department that we never had before. Between organizing, research, and political action, we had the ability to go to schools and talk to people about what meant the most to them. One thing we did was get and use data. We asked people, “What do you think? What do you want?” We went on listening tours for a year before.

We started talking to our members, building by building, pointing out that the board had given us a list of proposals that basically gutted our contract. Then we started with simple things like showing solidarity—wearing red on Friday. That became a big campaign and, as we got close to the end of the school year, people were wearing red everywhere. So a principal would say, “You can’t wear red on Friday.” We told our members, “Look, if you all wear red on Friday, the principal can’t write you all up. So here is a way to address your principal and show that you are in solidarity with one another.”

There are things that happen in a building that are out of the contract and there’s nothing you can do: “The principal’s being mean to me,” for instance. There’s no grievance you can write. But what you can do is figure out how to solve the problem. A lot of times if you talk to other members about a teacher who is being targeted by the administration, they’ll say, “Oh, that’s one of the crazies.” We tried to have our members embrace disaffected teachers rather than isolate them. “If the problem is over there now,” we said, “it’s going to happen to you next.” Because one of things that has been happening in Chicago is we have a very high turnover in principals, not just in teachers. They recruit very young people as principals, people who don’t see principalship as a culminating event of their career, but as a stepping stone. One of the problems with having young principals is, by and large, they don’t have the wisdom of experience. They tend to be more into control, more into data, as opposed to establishing good relationships with teachers and staff. Older, veteran teachers are frequently targets of new principals.

We discussed how to have relationships with people in the building you don’t necessarily like or agree with, how to conquer differences by doing things as a building, doing things in solidarity.

We also talked about having conversations with parents. I tell our members, “The first conversation you have with a parent cannot start with ‘Your child is driving me crazy.’ The first conversation should be about how glad you are to have their child in your class, what your plans are for the year, and saying, ‘If there is any help I can give you, please call me. I’m sure if we work together, we can make it be a great year for your child.’”

“We Won Some Respect”

JS: What are the most important things you won?

KL: You might be surprised. One of the things our members wanted was the ability to do their own lesson plans and not have lesson plans imposed on them. We’ve had problems with template lesson plans that are 30 pages long. For teachers, that was extraordinarily important. I’m probably going to be writing a grievance on that already. We have at least one principal who didn’t understand that part of the contract.

We got textbooks and materials on the first day of school.

For clinicians, we got a room with privacy, access to locked doors.

We got a paperwork reduction. If you add something you want us to do in terms of paperwork, you have to subtract something else.

We have an anti-bullying clause because we have some principals who are out of control; they stand up in front of the entire faculty and staff, and belittle and humiliate people.

But the most important thing we won is some respect we didn’t have before. The clear understanding that this union moves together. That was a very important win.

JS: What are the most important issues on which you had to compromise or put off a fight until later?

KL: One would be money. Also, we couldn’t bargain class size without the board’s agreement to put it on the table because it’s a permissive rather than mandatory subject of bargaining, and that means we couldn’t strike over it. It’s problematic that we could not lower class sizes.

JS: What are class sizes at this point?

KL: Depends on the grade level. K-3, we’re looking at 24; it goes up as high as 30 and 31 in 7th and 8th grade, core courses in high school are 28, but courses like PE, music, and art could be up to 40.

Moving Past “Color Blindness”

JS: When we talked shortly after your election as CTU president in 2010, you explained that one of the results of privatization and layoffs in Chicago (like elsewhere) has been the disproportionate firing of teachers of color, particularly African American teachers. Did the strike address that as an issue?

KL: I had to fight to get language in our contract that says that the district will actively recruit racially diverse staff. I had to fight to get the word racial put in our contract. The essence of the problem is so-called “color blindness.” This man who has a lot of power on the other side of the table said, “I don’t care what a teacher’s color is, I just want good teachers.”

I said: “But you are recruiting nothing but young white teachers. There’s a problem with that. There’s something wrong with your measurement of ‘good’ if the only people you’re hiring to work in Chicago are young white teachers who don’t stay here.”

I promised him, “I’m going to have a conversation with you about white privilege.” I haven’t been able to have that conversation yet, but now the strike is over, the contract is done, so we’ll see. There’s research on this; I’m not just making this up. There’s a whole field of academia on white studies.

But now we have language in our contract that includes the board being obligated to consult with us on a “systematic plan designed to search for and recruit a racially diverse pool of candidates to fill positions,” specific training for principals and head administrators on how to implement the plan, and union access to data and periodic meetings to assess progress. And we’re going to enforce that.

Changing the Conversation About Education

JS: How do you think the strike has changed the situation in Chicago?

KL: It has awakened a lot of labor unions to what solidarity looks like, what it means. We had so much support from police, from fire, from laborers, from all kinds of different places you wouldn’t necessarily expect. It says a lot about working people in Chicago, what kind of pressure we’ve been under.

The strike has changed the conversation about education in Chicago. It made clear that we are the experts on education, not these consulting firms, not these millionaire dilettantes. They have a lot of money to throw around, but they’re not educators. We have taken them to task for that.

It also brought to light that people actually like teachers. You do the polling and it turns out that people like teachers. They don’t like the union, but they like teachers. What we tried to show is that the union and teachers are one, we’re not separate entities.

JS: That hasn’t always been true.

KL: No, not at all. And that’s how Emanuel and his surrogates played it. They kept trying to separate the union from the teachers.

Over the years, before the strike, it was hard for us to get our story told. That was one of the things that my members complained about. By and large, traditional media is bought and paid for by wealthy white men. That’s not who we are. But during the strike, people saw us. They saw people who are knowledgeable. They couldn’t use the typical stereotype of the teacher—those who can, do, those who can’t, teach. They couldn’t find those stereotypes on our picket line. Don’t think they didn’t try, but they couldn’t find them.

JS: What about the union’s relationships with community organizations?

KL: We have had school closings and all kinds of dysfunctional stuff happening in Chicago since 2004. So we have built relationships with communities since then. This didn’t happen to us overnight. This CTU leadership has had experience working with community organizations for a very long time. We have a community advisory board. Unions never had that before. We’re trying to build a coalition of people and organizations to explore policy and have a voice, for goodness’ sakes—unlike other organizations that just tell you what you should be doing to support them. We really believe in the democratic process.

Women’s Oppression, Women’s Leadership

JS: There was such a strong presence of women at every level in the strike. Obviously part of that is because most teachers are women, but do you think there were specific ways that women’s leadership and women’s strength played a role in the Chicago events?

KL: I do. I think it’s part of the clash between myself and the mayor. I don’t think he’s used to anyone like me who can tell him no. I said, “Look, I want to work with you, but we have to have some modicum of respect here.”

I am a woman, so I don’t know what’s it’s like to be a man. I’m black. I don’t know what it’s like to be white, and being black is infinitely more problematic than being female; that’s my experience. But I’m looking at an assault on social services. Who provides those? This mayor closed down mental health clinics, curtailed library hours. How are you picking out social workers, librarians, and teachers? By and large, these are occupations that are done by women.

In the CTU today, all of our area vice presidents are women; we have a preponderance of women on our executive board and a preponderance of women in our house of delegates—because that’s the nature of teaching.

And it’s also why, by and large, teachers have allowed so much of this so-called “reform” to be done to us. Because we do want to be the “good” kids, we do want the approval. I say to the district, “Whatever you’ve told us to do, we’ve done. You said, ‘You need to get a master’s degree because that will make you a better teacher.’ So in droves we’ve gone and gotten master’s degrees. We’ve taken extra courses, we’ve taken extra endorsements, we’ve gotten national board certification. We’ve jumped through every single hoop.” But what is clear to me and to us as leadership is that they will never be satisfied. They will continue to move the bar until it is impossible to reach. Like No Child Left Behind: 100 percent of children have to be proficient. Really? They say we have low expectations. No, I don’t have low expectations. But I’m very clear that 100 percent of children are not going to be proficient for a variety of reasons, least of which is bad teaching.

Fighting with Our Tools, Not the Bosses’ Tools

JS: Every city is different, but are there things you have learned that could be helpful to teacher activists in other districts?

KL: I think a democratic, rank-and-file-driven union doesn’t hurt anywhere—a union leadership that is not only responsive but actively seeks input and advice from a variety of members, including people that you don’t necessarily share the same politics with.

Some people think you elect a president and the president makes all the decisions for the union. No, that’s not it, that’s not how it works. In the past, what we saw in Chicago was leadership that tried to stifle opposition. I think that opposition deserves to be heard and deserves to be part of the process. We had a very large rank-and-file bargaining team, 35 people. And they included people from all the different caucuses. Because we’re a large local, we have a lot of different factions. We felt that going into the negotiations, we needed to be on the same page with one another because this affects everybody. We went across the political divides and reached out to make that happen.

In a lot of locals, leadership is a little wary of trusting rank-and-file membership with the responsibility of negotiations, but I think it helps so much and informs the process.

And you need to provide good training for your members. We’re fighting a corporate strategy that’s trying to destroy public education. Union leadership needs to be really honest with its membership about whatever is happening in that community because I can guarantee you, wherever you are, you’re going to have a “Stand on Children” or a StudentsFirst, or a Democrats for Education Reform, or something similar. There is nothing like the disinfectant quality of sunshine. You need to point out who these people are, what organizations they belong to, what boards they sit on, how they intertwine with other people who are making decisions about public schools who are not public school parents, teachers, or kids.

It all comes down to how you teach people to fight with the tools they have. We have been fighting with the bosses’ tools. We can spend a lot of time doing legislation. I think that’s fine—have a legislative approach. But understand that you don’t control that process. We can talk about electing the right people, but ultimately, unless we have a state house full of teachers and paraprofessionals and clinicians, I don’t think we’ll get what we want coming out of state legislatures. You need to have good relationships with legislators; you need to have members get in touch and let them know what’s important to you. That’s one tool. But it’s not the only tool.

Our best tool is our ability to put 20,000 people in the street. I don’t care if one rich guy buys up all the ad space. The tool that we have is a mass movement. We have the pressure of mass mobilization and organizing.

And we have the first line of defense, which is the parents! We can see parents every day if we want to. Once parents believe that what you’re fighting for is something that’s good for their children, they’re on your side. If you’re just fighting for money, you’re never going to win the parents over. The parents don’t care, except in a situation like ours where we had a longer day—parents do understand about that—but you have to do the work to find out what it is their children really need.

Another tool is knowing what is on your members’ minds. A lot of union leaders tend to think for their members without asking them, “What do you think?” And you need to be honest. You need to say, “This is what we did get, this is what we’re going to try to get next time.” Because a contract is not the solution to all your problems. A contract will, by necessity, be a compromise. The key is to keep people engaged in the process of movement building.

JS: What’s next?

KL: There are 100 school closings coming up, so we’ll be focused on that. To complicate the issue, CPS has separated school “turnarounds” from school closings. They have agreed not to close any schools because of performance, but they will probably hand some off to the Academy for Urban School Leadership [a Chicago program similar to Teach for America linked specifically to “turnaround” charter schools]. The turnaround model is responsible for the loss of veteran teachers, especially black teachers, from the system. AUSL actively recruits people from out of Chicago by using ads on social media in places like Texas: “Do you want to help underserved kids in Chicago?” Blatantly pulling on the heartstrings. Nowhere does it say, by the way, that you’ll be putting middle-aged black women out of work. These policies have destabilized neighborhoods and destroyed families, but no one has been held accountable for that.

So we will continue our work to change the discussion—from punishing and publicly humiliating students, parents, teachers, paraprofessionals, and clinicians—to how we can work together to build a school system based on respect for all our communities.