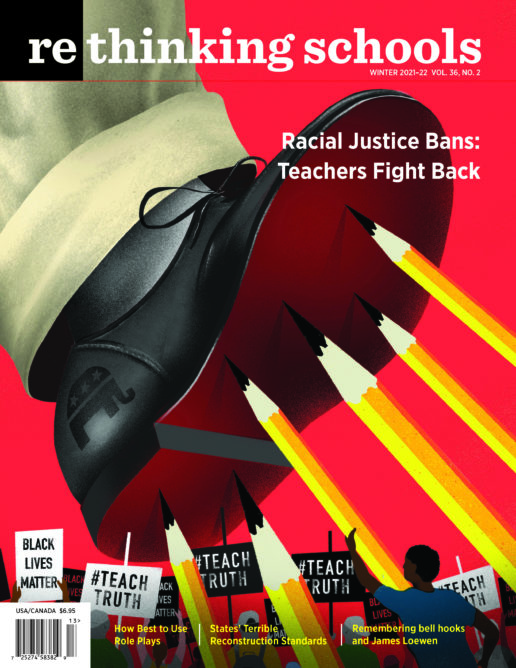

Learning from — and Mourning — James Loewen

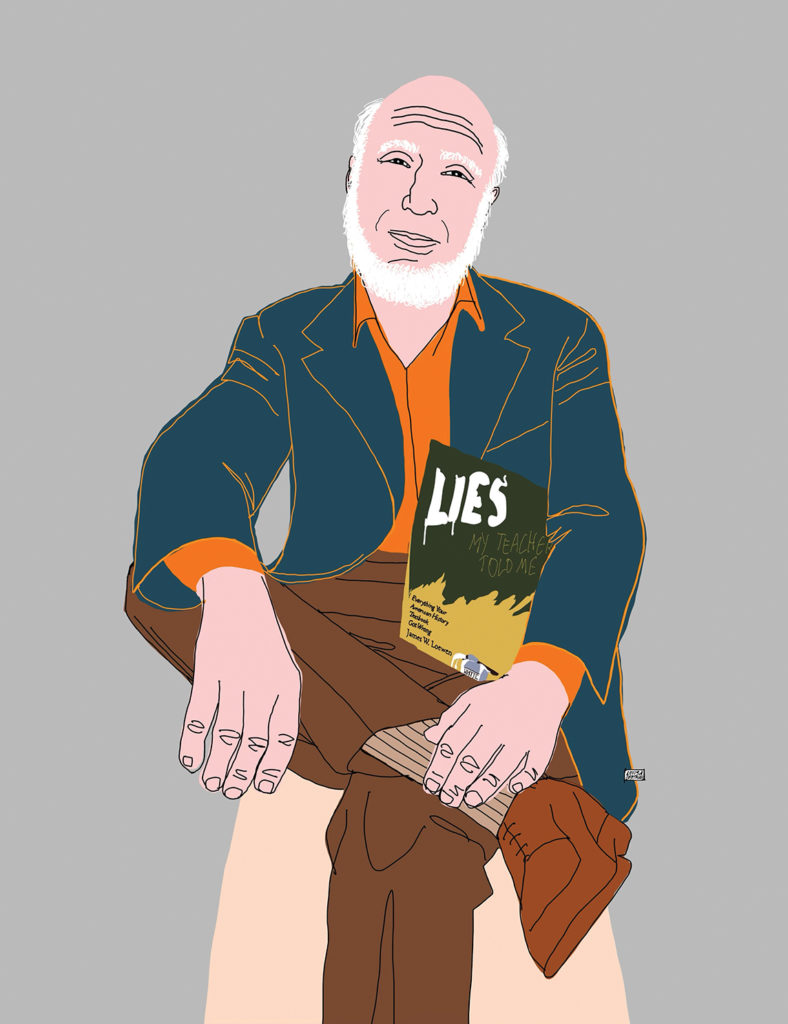

Illustrator: Louisa Bertman

“Telling the truth about the past helps cause justice in the present.” Those words should animate every history class in the world. They are from Jim Loewen, the brilliant, indefatigable, funny, warm, scholar, activist, and author of Lies My Teacher Told Me, who passed away Aug. 19, 2021, at the age of 79. To those words, Loewen added: “Achieving justice in the present helps us tell the truth about the past,” emphasizing that the fairer our society becomes, the more clearly we can understand our history.

Although Loewen joked that he is better remembered for his quote: “Those who don’t remember the past are condemned to repeat the 11th grade.”

There are tens of thousands of moments of consciousness raising that can be traced back to Loewen’s work. When the Zinn Education Project posted a notice about his death, tributes from educators poured in.

“Lies My Teacher Told Me has served as an equity lighthouse guiding me through an ocean of historical myth and amnesia,” said Jessica Rucker, a high school teacher in Washington, D.C.

“Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States made me want to be a history teacher and James Loewen’s Lies My Teacher Told Me gave me the drive to want to teach beyond the classic textbook-driven curriculum,” said Cincinnati social studies teacher Maureen Andreadis. “Loewen’s work has profoundly affected my teaching practice by cementing the commitment to instructing students to question and inquire as they ‘do’ history.”

And former D.C. State Board of Education member Tierra Jolly said, “I read Lies My Teacher Told Me the summer between middle and high school. It’s the No. 1 reason I became a high school social studies teacher.”

***

As a Carleton College student in the 1960s, Loewen was introduced to racial injustice when he lived in a dorm at Mississippi State University from January to March 1963, which, according to Loewen was then the largest segregated all-white higher education institution outside of apartheid South Africa. While in the South, he also spent time at African American institutions: Tougaloo College and the Tuskegee Institute. He returned to the South to teach from 1968 to 1975 and ultimately chaired the sociology department at Tougaloo. Discovering the wretched and white supremacist Mississippi history textbook used in the required 9th-grade course, Loewen co-wrote Mississippi: Conflict and Change. Despite winning the Lillian Smith Award of the Southern Regional Council for best nonfiction book on the South, Mississippi’s state textbook commission rejected it for use in schools by a 5-2 vote, along racial lines. In 1980, a federal judge overturned the textbook commission and ordered the book adopted for use in Mississippi schools.

Loewen later taught at the University of Vermont and, during a Smithsonian fellowship, researched and wrote his classic Lies My Teacher Told Me, a funny and blistering critique of 12 major U.S. history textbooks. In our Rethinking Schools review of Lies in 1995, we wrote:

The core of Loewen’s critique is that because of the texts’ wretched portrayals of the past, students can’t help but be befuddled by the present. The books fail to consider why anything happens in society. Events appear as inevitable because, as Loewen found, the texts never indicate that throughout history there were choices, that people posed alternatives. Consequently, students are discouraged from thinking of the present as a place in history with different potentialities, dependent largely on how we analyze society and work for change.

Perhaps the greatest accomplishment of Loewen’s book is its insistence that we must take textbooks seriously as literature that imparts significant, often reactionary, messages. Lies asks who benefits and who suffers from particular versions of history-telling. And if its answers are not complete, Loewen’s book nonetheless forces us to think about the nature of our society and what is worth teaching about its origins.

When Jim Loewen learned of his terminal illness a couple of years ago, he rushed to complete a number of projects, including a short memoir and a new website (bit.ly/Loewen1). Recognizing he would not get to everything on his list, he added a section to his website called Unfinished Projects in the hope that others would pick them up. In typical Loewen humor, his life story on the site includes everything from childhood stories to a photo of his tombstone. The site is also the home of his extensive database on Sundown Towns (bit.ly/SundownLoewen) — sites where residents enforced a whites-only requirement for anyone after “sundown.” Loewen’s magnificent work on sundown towns has been especially valuable as people throughout the United States work to come to grips with how racism has shaped our communities.

Loewen left a robust collection of books, articles, interviews, and generations of teachers he inspired to teach outside the textbook. Rethinking Schools editors and staff mourn his loss but will continue to be inspired by his work.