Preview of Article:

Kalamazoo’s Promise: What Happens When All Students Are Guaranteed College

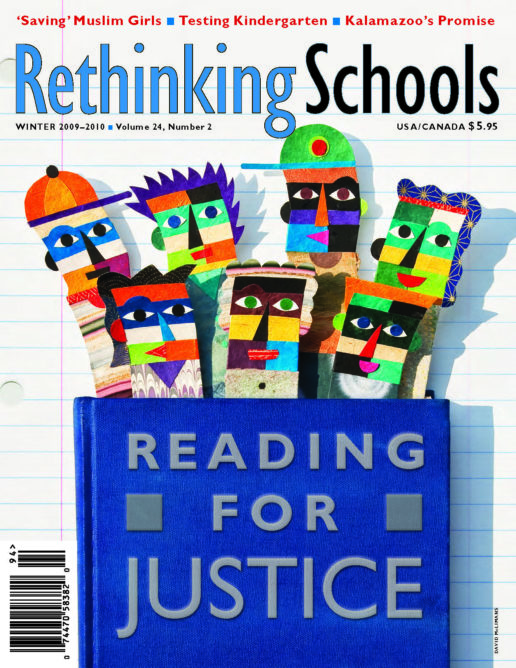

Illustrator: Colin Johnson

When Den’Asia* dropped out of school in the 11th grade, she already had a 2-year-old son and no ambition to go to college. “I didn’t have a strategy,” she says. “I was just going to get a job and save money.” Two years later, as Den’Asia recounts her journey to me, she is back at her high school as a senior. Now she has a five-year plan that includes degrees in nursing and business. She is already dually enrolled in courses at the local community college.

Her shift back to a focus on academics is part of a movement that started in 2005 with the implementation of the Kalamazoo Promise. In what may have been the most exciting school board meeting in history, the superintendent of the Kalamazoo, Mich., Public Schools announced the Promise—a scholarship to any public college or university in the state of Michigan for all Kalamazoo public school graduates, funded by a group of private, anonymous donors. The scholarship is awarded on a sliding scale, but unlike most scholarships, isn’t based on grades or good behavior. Attendance through graduation is key. Students attending Kalamazoo Public Schools since 9th grade have 65 percent of their tuition paid by the Promise. For each preceding year of attendance, the amount of the scholarship increases, so that students entering the school system in kindergarten have a full scholarship to college.

As educators and policymakers across the country search for ways to keep students in school and confront the yawning achievement gap, the Kalamazoo Promise holds out hope and possibility. Early data indicate that when students are guaranteed college tuition, many of those who need it most will indeed stay in and even return to school. And when students know that college is in their future, this knowledge can begin to inspire them to greater academic performance.

But the race and class conflicts and inequalities in Kalamazoo cannot be swept under the rug. These conflicts came to light when I spoke with students, teachers, principals, community leaders, city officials, and parents as a program evaluator for a U.S. Department of Education study of the Kalamazoo Promise. Our interviews were always confidential, which is why most quotes in this article are anonymous. I often wonder whether issues of race and class would still have surfaced had I not promised to keep private the identities of the interviewees.