It’s Imperialism.

How the textbooks get the Cold War wrong

Illustrator: "It's Imperialism" art by Michael Duffy

My 11th-grade U.S. history students and I were coming to the end of our unit on the Cold War last year when news broke of Russian meddling in the U.S. presidential election. As we discussed news articles about the reported foreign interference, my students were incredulous: “Why is the media making such a big deal about this? What the Russians are being accused of is nothing compared to what the U.S. did in Cuba!” This comment, which came from Max, a politically middle-of-the-road kid in my suburban high school, was repeated again and again in the coming days with slight variations. Sarah said, “I mean I know it’s bad to have the Russians hacking us, but it’s not like anyone died. In Congo, the leader was killed.” David agreed and added, “I just think it’s totally hypocritical of the U.S. to be so angry. We did this sort of thing to lots of countries during the Cold War.”

My students were clearly fired up by their newly acquired Cold War knowledge. But overall, the Cold War is a curricular conundrum for teachers of U.S. history since it lasted so long, spanned so many administrations, and involves so many different locations of conflict and intervention. And it’s no surprise that traditional history textbooks offer no solution. Pearson’s The American Journey, the adopted textbook for my 11th-grade students, has a stand-alone chapter titled “The Cold War at Home and Abroad: 1946-1952.” This chapter emphasizes competition between the Soviet Union and the United States in postwar Europe, the rise of the National Security State, and communism in East Asia — the establishment of the People’s Republic of China and the Korean War. Since the authors of The American Journey insist on maintaining a chronological approach, this chapter does not include Cold War policies of the later 1950s or the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. If you want to learn about Cuba, Vietnam, or Nicaragua, you will need to dig through other chapters that follow the stale and triumphalist march of presidencies. And if you want to understand what motivated the overthrow and assassination of Allende in Chile, or Lumumba in Congo, you are out of luck.

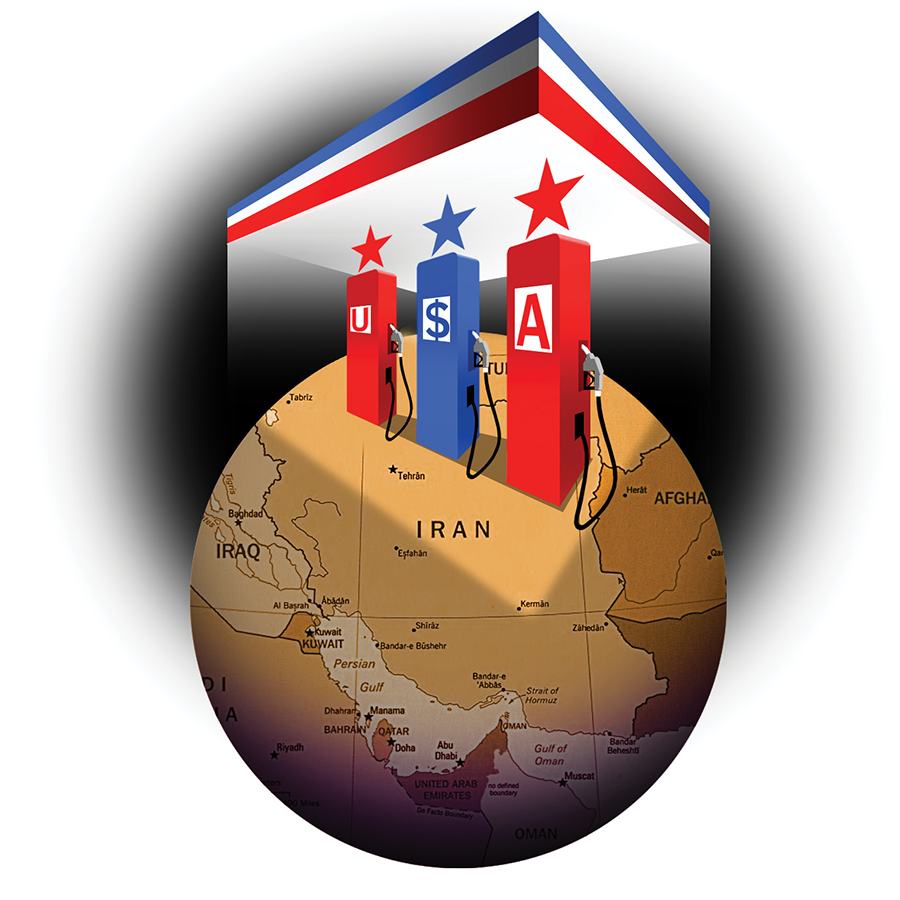

However, even when The American Journey does include some of these important events, readers come away less than enlightened. Take this paragraph, which appears under the heading “Containment in Action”:

Twice during Eisenhower’s first term, the CIA subverted democratically elected governments that seemed to threaten U.S. interests. In Iran, which had nationalized British and U.S. oil companies in an effort to break the hold of Western corporations, the CIA in 1953 backed a coup that toppled the government and helped the young Shah, or monarch, gain control. The Shah then cooperated with the United States until his overthrow in 1979. In Guatemala, the leftist government was upsetting the United Fruit Company. When Guatemalans accepted weapons from the Communist bloc in 1954, the CIA imposed a regime friendly to U.S. business.

Although The American Journey rises above some of its competition for even including U.S. actions in Iran and Guatemala at all, one cannot ignore its sanitized and ambiguous language. Why do the authors define “Shah” but not “nationalized”? Surely these two words would be equally unfamiliar to most adolescents in a U.S. classroom. Without really understanding the economic impact on foreign business interests when governments take control of key industries or land holdings, it is hard for students to see clearly what was motivating these coups.

And what about the verbs used in The American Journey’s account? They are so vague as to put one to sleep, obscuring the incredible drama and insidiousness of the actual events. The American Journey says the CIA “backed” a coup in Iran; in reality that “backing” involved Kermit Roosevelt, CIA agent and grandson of Theodore Roosevelt, arriving in Tehran with suitcases full of cash to manufacture an opposition movement by literally paying people to protest, bribing newspaper editors to print misinformation (fake news!), and creating a sham communist party to act as a straw man. The American Journey says the Shah “cooperated” with the United States; it leaves out that such “cooperation” was defined by Iran’s purchase of billions of dollars’ worth of weapons from the United States as well as the CIA’s training of Savak, the Iranian secret police force infamous for its human rights violations. The American Journey says the Guatemalan government was “upsetting” the United Fruit Company; it fails to explain that United Fruit controlled 42 percent of Guatemalan land and that Jacobo Arbenz’s policies of nationalization posed a threat to its profits. The authors of the passage seem strangely unconcerned with asking students to think about why a private business might be directing U.S. foreign policy in the first place.

Ultimately, there are three central problems that have led me to altogether abandon The American Journey’s — and most textbooks’ — treatment of the Cold War in favor of my own cobbled-together curriculum. First, important events are just not there. Today, Congo and Afghanistan are regularly cited as among the most unstable places in the world. But how did they get that way? The Cold War history of these nations — which is also U.S. history — is nowhere to be found in our textbooks. Second, what students do learn about U.S. interventionism is sanitized, obscuring the significant harm and disruption caused by U.S. policies. Third, because Cold War content is spread over so many chapters, U.S. intervention abroad seems disjointed and haphazard rather than methodical. By just glimpsing one thread here and another thread there, textbooks do not invite students to see the whole tapestry of U.S. Cold War actions that persistently, regularly, and systematically undermined democratic movements around the world.

Textbooks usually embrace the dominant and deceptive periodization of U.S. history that would have us learn something called “Westward Expansion” separately from “U.S. Imperialism” separately from “The Cold War.” In reality, these are better understood as a continuum. From its birth as a nation, the United States never stopped being imperialist. The political, economic, racial, and religious rationales used to justify the theft of Indigenous land on this continent were the very same trotted out in 1893 and 1898 to steal the faraway lands of Hawai’i, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico. The same insatiable greed for resources that led U.S. sugar barons to overthrow Queen Lili’uokalani also fueled United Fruit’s seizure of land across Central America and its collaboration with the CIA to install business-friendly regimes there. So in my U.S. history curriculum, the Cold War lives in a larger, quarter-long unit on U.S. imperialism that places the theft of Hawai’i alongside U.S. support for the Contras, and the Spanish-American War alongside the Vietnam War.

The Cold War Group Essay

I taught the lesson described here after a two-week investigation of U.S. policy in Cuba and before a three-week unit on the Vietnam War. These case studies were the Cold War unit’s deep dives. But I also wanted to have students grapple with the sheer number of geographic sites of U.S. intervention during the Cold War, and grasp that the dramatically antidemocratic behavior of the U.S. in Cuba and Vietnam was not unique. The Cold War Group Essay sought to address those goals.

Day 1

The lesson spanned two classes that, at my school, are each 90-minute blocks. I began the lesson by saying, “OK folks, today we are going to continue investigating the Cold War by having you each learn about a different place where the U.S. government got involved.” I explained that though one could blindly throw a dart at a map and likely hit a site of U.S. Cold War conquest, we’d narrow our focus to just six places. I assigned students to Iran, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Afghanistan, Congo, or Chile. I told students they would be doing independent research about U.S. policies in each of these places. Because many students were shocked by what they’d just learned about Cuba in the weeks prior to this lesson, I used references to U.S. policy there to pique their interest: “Just like Cuba, these are all places where the U.S. government carried out operations that were kept secret from the public. You’ll be finding out about more spying, more covert action, more assassination attempts.”

Consulting a couple of websites for each country, students used five questions to guide their research:

1. Interests: Why did the U.S. government care about this place? Interests can be economic (U.S. business investments in an area, for example), political (alliances), strategic (militarily important), or some combination of the three.

2. Threat: What did the United States fear or object to in this place? What was the United States attempting to combat, fight, defeat, or prevent?

3. Action: What did the United States actually do in this place and how was it done?

4. Effectiveness: Did the United States achieve what it set out to do?

5. Consistency with American ideals: Did U.S. policies match up with stated U.S. ideals of democracy, self-determination, and economic freedom?

I hoped that the first three questions would help students collect facts about what happened while the final two questions would foster analysis and evaluation.

Because the sources can be dense and confusing, I made sure students did this research in class, which allowed me to walk around and answer questions, of which there were many:

“This says that the Afghan PDPA was ‘Marxist.’ What’s that mean?”

“So wait, did the United States support the Somoza regime or not? It’s confusing.”

“This says that Mossadegh ‘nationalized’ the oil industry in Iran. What does that mean?”

“Why did the CIA train rebels in Honduras?”

“What’s a coup?”

My students were not experts at the end of this research; there were still big holes in their understanding and knowledge. But I was OK with that since I knew (well, I hoped) the deeper learning would take place the next day.

Day 2

As they came into class, I asked students to sit in country groups for a quick share and review of their research. I said, “Everyone who learned about Afghanistan meet by the window! Everyone who researched Chile meet at the front table. . . .” Once students were congregated, I asked them to discuss their answers to the five research questions. I encouraged students to fill in gaps, clarify confusing points, and build confidence for the next task, where they would be the sole source of information about their place. I let this discussion go on for only about 15 minutes, as I wanted to reserve plenty of time for the main part of the lesson.

Next, I asked students to get into mixed groups, so that each table included someone who knew about each country. When I revealed that they would be drafting a group essay, I heard a fair number of groans accompanied by comments like “Another one?” and “Sheesh, Ms. Wolfe, how many of these are we going to do this year?!”

As you may have guessed from my students’ familiarity with the strategy, I love group essays. I have found that asking kids to write together generates sophisticated and in-depth discussion, true collaboration, and can be a wonderful way to coax a rough draft out of reluctant writers. In spite of my students’ prior experience with the format, I reviewed the basic guidelines one more time:

- No introduction or conclusion — just a claim (thesis) and substantial developing paragraphs.

- The writing of the essay happens through conversation.

- Every sentence — Every. Single. One. — is written collaboratively and out loud.

- Everyone takes a turn putting those sentences on paper, being the scribe.

- No sentence should show up on paper until all members of the group are satisfied with it.

Before they got to work, I handed out the essay prompt and debriefed it with the class. The prompt was: “Describe and evaluate the U.S. government’s impact on the globe during the Cold War.” To clarify what I meant by “describe” and “evaluate,” I returned, again, to the Cuba example that was still fresh in their minds. I said, “If I asked you to describe the U.S. government’s impact on Cuba during the Cold War, what would you say?” My students quickly generated a list:

“The CIA destroyed sugar crops.”

“Kennedy tried to overthrow the new government after the revolution.”

“The CIA plotted to assassinate Castro in Operation Mongoose.”

“Right,” I say. “So that’s what happened. Now what if I asked you to judge or assess or evaluate those policies. What would you say?”

“The U.S. acted like a bully.”

“The U.S. was obsessed with fighting communism.”

These answers were pretty general and I wanted to push further: “OK, but can you say more about the impact and outcome of U.S. policy in Cuba? Was it a success? A failure? Something else altogether? Was the action something U.S. citizens should be proud of?”

They fired off some answers: “It was counterproductive, because the Bay of Pigs actually made Castro more popular with Cubans.”

“Yeah, and it made a lot of Cubans hate the U.S.”

“The Cuban Missile Crisis might not have happened because Castro might not have turned to the USSR if he didn’t feel threatened by us.”

“It was not something we should be proud of because the U.S. was acting like Cuba was still a colony rather than a free country.“

“Great,” I said. “That is just the kind of conversation you’re going to have in your groups, but this time about six different places, rather than just one.”

Once students had a sense of the kind of thinking I was looking for, they started by going around the table and sharing a summary of their research. “Tell it like a simple story,” I suggested. Referencing their research questions, I said, “Make sure to include interests, threat, action, and outcomes.” I told students that as they listened to each other they needed to keep track of patterns, similarities, and unifying themes. It didn’t take long for me to hear the hopeful hatching sounds of their preliminary analysis.

“That’s a lot like what happened in my place!”

“The CIA trained rebels in Nicaragua, too.”

“In my case, the leader was just overthrown, but in your case, he was actually killed.”

“In both Iran and Guatemala, the leaders were sort of tricked into stepping down.”

After everyone had shared, I asked students to plan their essay. “Now,” I said, “you need to develop a handful of arguments about the U.S.’s impact on the globe during the Cold War.” Before I even finished my explanation, a hand shot up to ask, “How many arguments do we need?” I clarified that I was happy with two, three, or four. “The most important thing,” I emphasized, “is that you identify patterns, things that the case studies have in common.” This step took about 20 minutes as students engaged in their analytical heavy lifting.

As I walked around the room, I heard a lot of false starts that grew into supportable arguments. For example, Brad, who had researched Congo, said, “Well, didn’t the United States assassinate leaders in most of these places?” Brandon, who had researched Iran, said, “In my country, the leader wasn’t assassinated, just removed from power.” “Yeah,” added Stella, “And I don’t know that we can say the U.S. actually assassinated leaders. It seems more like they planned or supported other people who did the dirty work.” Slowly, students verbally tested each provisional argument against each other’s specialized knowledge of each case study.

I did a fair amount of coaching (students might call it interrupting) as I eavesdropped on conversations. One group got caught up arguing about the motivations behind U.S. intervention, with some students advocating U.S. fears of communism and others arguing for U.S. investments. I interjected to suggest, “I wonder if you could look at it differently; maybe it’s not either/or. Maybe the U.S. government’s dislike of communism had to do with its concern for U.S. investments if communist or socialist parties came to power.” Another time, I heard a group say, “The U.S. installed democratic governments.” I sat down and said, “Let’s look at this language. Can democratic governments be ‘installed’ by a foreign power? Were these governments supported by the people?”

Here are some of the arguments students crafted during this process:

- Over the course of the Cold War, the U.S. broke the right to self-determination by overthrowing government leaders and installing the U.S.’s chosen leaders.

- While the U.S. did not directly engage in warfare in most countries during the Cold War, they left a militaristic impact by fighting wars of proxy and using covert action.

- Not only did the U.S. install leaders into power, but these people systematically violated rights.

- The United States put a high priority on economic interests during the Cold War.

Once students settled on their arguments, I told them to get started on a thesis. Knowing that kids often suffer from thesis anxiety, I said, “Don’t get too hung up on this part. You already have all your arguments laid out. So you just have to figure how to respond to the prompt in a way that matches up with your main points.” I gave students only about 10 minutes to write their statements, which forced them to work fast. Still, they came up with some good material. Parker’s group wrote: “The United States’ foreign policy during the Cold War took advantage of developing nations to disguise its imperialistic intentions, thus having an ultimately detrimental impact around the globe.” Katharine’s group wrote: “The United States during the Cold War impacted the globe by focusing on implementing leaders who were pro-West, keeping U.S. economic interests secured, and trying to stop the spread of communism at the cost of democracy.”

Finally, students were ready to flesh out their paragraphs. I explained that each assertion should be developed with supporting information from multiple case studies. I reminded them, “This really means you have to write collaboratively, because every paragraph requires information from several of you.” Since class time was by this point growing scarce, students worked at a feverish pace. But because the essay relied on the individual knowledge of all the students, it was a truly collaborative frenzy and a joy to witness. Only the student who had researched Iran could tell the scribe how to spell “Mossadegh” or “Shah”; only the student who had researched Nicaragua could answer the question “Should we call the Sandinistas communists or socialists?”; only the kid who had researched Chile could say exactly what economic interests guided U.S. policy there.

Here is a paragraph from Caleb, Austin, Connor, Matthew, and Robert. They wrote:

The United States put a high priority on economic interests during the Cold War. In Iran, the United States received access to 40 percent of its oil fields as a reward for restoring the Shah to power. The United States also became involved in Afghanistan to protect oil interests in nearby countries from Soviet influence. In Congo, the U.S. feared its mineral interests were in danger of Soviet control, which led it to seek a leader that would ensure access to these minerals. In Guatemala, the U.S. had three huge companies that owned 42 percent of the land. These investments were threatened by the nationalist policies of the leader, Arbenz.

One can certainly critique this paragraph’s development — each point needed elaboration and more evidence — and I would have used Chile rather than Afghanistan as an exemplar of the main idea. But since students completed their whole essay in about an hour, if I expected greater exposition and detail, I would have to award them more time. I was content with these quick-and-dirty paragraphs because they fulfilled my hope for the lesson: Students described the basic features of U.S. Cold War policy — myriad forms of political, economic, and military intervention — and reckoned with the vast reach of U.S. state power during that era.

Still, with the benefit of hindsight, I saw some weaknesses in my lesson. Although students walk away with a strong sense of the U.S. government’s actions during the Cold War, they get little sense of how those actions manifested in the daily lives of real people. Where are the voices of the farmers and workers, soldiers and activists, priests and poets, who had to navigate the disruption, instability, and violence that were so often the outcome of U.S. interference? In the future, I might add a follow-up lesson where students read poems, narratives, and oral histories — pieces that highlight people over policies.

Russia and the 2016 Election

I had mixed feelings as I listened to my students take what they had learned about the Cold War and apply it to the case of Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election. On one hand, I was heartened by their command of U.S. policy, their alertness to U.S. hypocrisy, and their ability to draw historical parallels with current events. On the other hand, I was demoralized by the cynicism at the heart of their comments, which amounted to shrugging off the Russian meddling as less despicable than what the United States did in many places across the globe. I want students to learn about the considerable damage U.S. Cold War policies did to nations like Congo, Chile, and Guatemala, not so that they let the lesser evil (in their eyes) of the Putin regime off the hook, but so they can critique and hold accountable all powerful interests that use their might to undermine democratic processes and institutions.

How to combat their darkly resigned sense that “Well, it sucks, but that is just what powerful countries do”? The answer might be, as it so often is, more stories of resistance, both inside and outside the United States. Students deserve a chance to see more about how folks coped with, organized against, and responded to U.S. imperialism. The Central America solidarity movement of the 1980s strikes me as a good fit here — having birthed the modern U.S. Sanctuary Movement, it would also be a rich tie-in for looking at current debates about refugees and immigration.

As we wrapped up our discussions of Russian election interference, I asked my classes whether they thought the United States might be engaged in similar actions around the globe today. My students were emphatic and in total agreement: Of course. “And what about actions like those the United States took during the Cold War?” I asked. Here there was less certainty. “Well, I don’t think we go around assassinating world leaders anymore,” said Amit. “Yeah,” said Drew, “but we do still overthrow leaders — like in Iraq.” Maddie rejected this corollary: “But, that’s different. We were fighting terrorism and the leader was a dictator.” “I don’t know,” piped up David. “I think the U.S. is over there for the oil and that seems pretty similar to the Cold War.”

As this discussion makes clear, there was much teaching and learning still to be done in my classroom about the current role of the United States in the world. As we pursued that knowledge, I hoped that the Cold War would be a crucial point of comparison and historical foundation, attuning students to not just the military escapades that make the front page, but also to those that don’t. I want my students to be skeptical when political leaders demonize regimes in places like Iran without taking account of the United States’ own history of wrongdoing there. Students need to know the frequency with which the U.S. state acts on behalf of capitalism rather than on behalf of the people it professes to represent.

Finally, the history of the Cold War asks students to consider what right the U.S. government has to interfere with and plot against other nations simply because they stand in the way of its political and economic goals. The perpetual interventionism and global hegemony exercised by the U.S. government during our students’ own lifetime has been so normalized as to appear to be an almost original historic condition, as Michael Parenti puts it — as if it has always been this way. If we are ever to create a different world, one in which the United States does not cast an outsized and militarized shadow across the globe, we need our students to understand how and why that shadow was created in the first place.

Resource

The National Security Archive has made an art of using the Freedom of Information Act to access once-classified government documents. It puts together excellent briefing papers summarizing and explicating document collections. Students love the drama of opening old typewritten CIA memos stamped CLASSIFIED, defaced with black swathes of redaction. https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/

Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (ursulawolfe@gmail.com) teaches at Lake Oswego High School in Oregon and writes frequently for Rethinking Schools.