Ignoring Diversity, Undermining Equity

NCTQ and Elementary Literacy Instruction

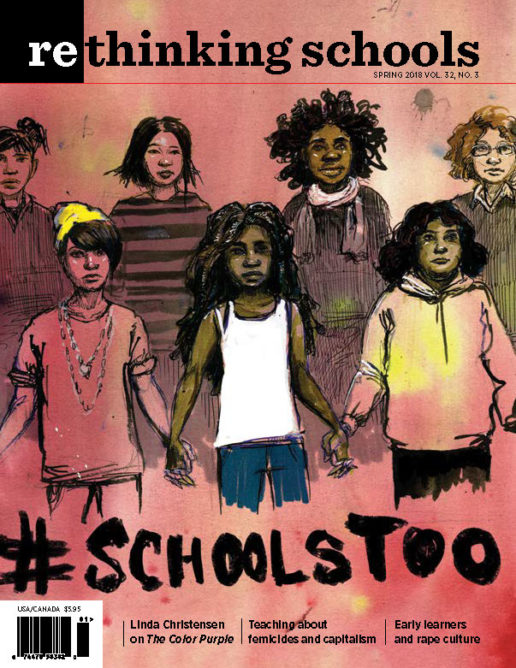

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

It’s the end of my first year as an assistant professor at the University of New Mexico, a Hispanic-Serving Institution in the urban Southwest, I was unexpectedly called to a meeting with the dean of my college to discuss a forthcoming evaluation from the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ), a political advocacy organization that has published a number of high-profile reports aimed at ranking and sorting colleges of education and teacher preparation programs. As a literacy professor tasked with teaching reading methods courses, I am accustomed to being in a high-stakes field where theories of how best to prepare teachers to teach reading are highly contested and polarizing. In spite of this, I was unprepared for my encounter with the dean who was gravely disappointed that NCTQ had docked our institutional rating by several points as a direct result of revisions I made to an elementary reading course. As a new professor who had inherited the course from someone else, I made several substantial changes to the syllabus based on my experience as an elementary school teacher in Washington, D.C., as well as my expertise as a scholar in the field of literacy.

One fundamental change was the addition of multicultural children’s literature — including texts like Locomotion by Jacqueline Woodson Ñ that I hoped would help preservice teachers recognize the importance of grounding literacy skill instruction within the context of culturally relevant literature. Secondly, I introduced critical literacy frameworks, which focus on issues of power and privilege and the importance of introducing and grappling with multiple perspectives. I anticipated that the inclusion of critical literacy would encourage the preservice teachers to question the efficacy of the mainstream textbooks and corporate reading programs they were often required to use.

According to the dean, NCTQ found these additions “distracting” and questioned whether I was prioritizing the “five pillars of reading instruction” as outlined by the National Reading Panel (NRP) report, which include phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. With the hope of improving our score in subsequent years, the dean requested that I remedy this issue by adopting a textbook from NCTQ’s approved list of books which privilege “scientifically based” perspectives on reading instruction and generally ignore issues of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic diversity. She also suggested that I speak to a consultant who could ensure that our college syllabi aligned with NCTQ’s expectations. Notably absent from the discussion was any mention of what my students thought of the course and whether or not they felt prepared to teach reading. Unfortunately, my experience at the University of New Mexico is not an isolated account as the reach and the scope of neoliberal entities like NCTQ continue to expand.

NCTQ: Who Are These Folks?

NCTQ, which claims to “provide an alternative national voice to existing teacher organizations and to build the case for a comprehensive reform agenda that would challenge the current structure and regulation of the profession,” was created by the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation in 2000 and incorporated in 2001 as a policy response to a perception that colleges of education were not adequately preparing teachers. According to education historian and NCTQ critic Diane Ravitch, the conservative members of the Thomas B. Fordham foundation perceived teacher training as problematic due to an overemphasis on social justice and a lack of focus on basic academic skills and abilities. Thus, NCTQ was originally founded as an entity through which to encourage alternative certification and circumvent colleges of education. Indeed, early on, NCTQ was closely connected to ABCTE (American Board for the Certification of Teacher Excellence), which created a series of tests that potential teachers could pass in order to bypass teacher education programs altogether by paying $1,995.00.

Aside from connections with alternative certification efforts that fundamentally weaken the teaching profession, NCTQ bases its rankings of teacher education programs on dubious data points. Although NCTQ claims to use 11 different indicators to rank programs (syllabi, required textbooks, institutional catalogs, student teaching handbooks, student teaching evaluation forms, capstone project guidelines, state regulations, institution-district correspondence, graduate and employer surveys, state data on institutional performance, and institutional demographic data), the organization apparently relies most heavily on an analysis of syllabi. This reliance on artifacts and the refusal to conduct in-depth site visits undermines NCTQ’s credibility and raises questions about the organization’s motives, as a review of syllabi and other programmatic artifacts offer only a narrow window into the work of a teacher education program.

Chained to the National Reading Panel Report

In critiquing and reviewing reading syllabi, NCTQ makes the criteria clear: NCTQ’s expert reviewers systematically assess whether these documents include language from the National Reading Panel report (2000), specifically language related to the five pillars of reading instruction as noted above. According to NCTQ reviewers, if these topics are not explicitly listed on the syllabus, then the syllabus is considered inadequate. In fact, NCTQ even notes on its website that the most common reason that programs do not earn a high ranking is that the syllabus “does not adequately address two or more essential components of effective reading instruction. Preparing teacher candidates to teach reading by covering some but not all components is like asking candidates to sit on a two-legged stool” (www.nctq.org). This emphasis on the five pillars of reading instruction aligns closely with a back-to-basics perspective on literacy instruction favored by self-styled reformers who insist upon standardized, homogenized curricula. NCTQ gives no credit to syllabi that address working with readers from different racial, cultural, economic, or linguistic backgrounds.

Interestingly, most of the reviewers responsible for assessing the syllabi do not have doctoral degrees in literacy and none of the reviewers listed on the website is a tenure-track professor working to build an effective teacher education program. Further, many of the reviewers had been connected, directly or indirectly, with George W. Bush’s Reading First initiative, which allocated nearly 5 billion federal dollars to improving early reading instruction in Title 1 schools by using scripted reading programs that focused almost exclusively on the five pillars of “scientific reading instruction.” By all accounts, Reading First was an unequivocal failure, resulting in no gains in reading achievement across a five-year period, according to a 2008 Institute of Education Sciences study.

In addition, the Bush family had a stake in the corporate reading programs that schools were required to adopt under Reading First and benefited financially from the legislation (Roche, 2006).

Moreover, literacy scholars have critiqued the NRP report both for the limited range of studies they utilized in compiling the report (only 500 out of nearly 100,000) and the possible motives of the legislation in supporting corporate interests in education (Coles, 2003). A member of the panel, Joanne Yatvin, past president of the National Council of Teachers of English, documented her experience on the team, casting additional doubt on the validity of the report. This litany of critiques is never mentioned by NCTQ; rather, the organization operates on the ideological assumption that “scientifically based” reading instruction will dramatically improve reading achievement on a national scale. Yet the NRP report is now nearly two decades old and the robust number of literacy studies conducted in the interim continue to be excluded as factors in key policy decisions.

Textbooks that Ignore Issues of Culture and Diversity

In addition to focusing solely on the five pillars of effective reading instruction in assessing syllabi, NCTQ also discredits teacher education programs that do not use one of their approved textbooks. According to NCTQ’s standards for early reading instruction, for example, “With a number of strong textbooks readily available, instructors should require texts that adequately and comprehensively cover all five essential components of reading instruction.” In order to help instructors identify “strong textbooks,” NCTQ has created a spreadsheet that rates reading textbooks indicating whether or not they are acceptable to use in university literacy methods courses. Again, one of the primary bases for ranking textbooks is whether or not the books privilege the five pillars of effective reading instruction as outlined by the NRP report.

Not surprisingly, the textbooks that NCTQ deems acceptable favor a technical and mechanistic approach to teaching reading and have titles like Assessing and Correcting Reading and Writing Difficulties (Gunning, 2013) and Strategies for Teaching Students with Learning and Behavior Problems (Bos & Vaughn, 2012), which suggest that teaching people to read is simply a matter of “remediating” their deficiencies with neutral, skills-based instruction.

Not surprisingly, this mirrors the approach to reading instruction currently at place in schools across the United States, one that remains unsuccessful in producing literate students capable of participating in a democratic society. For example, none of the textbooks included on NCTQ’s approved book list focuses on issues of diversity, social justice, or even writing instruction. Moreover, NCTQ disqualifies the majority of books written by leading scholars in the field of literacy. In this sense, teacher education programs that strictly abide by NCTQ’s guidelines are forced to disregard decades of reading research and scholarship, much of it focused on working with diverse learners, in favor of a back-to-basics view of reading instruction.

As a teacher educator in a state that serves students from a multitude of ethnic and cultural backgrounds, I take a different stance to literacy instruction, believing it is essential preservice teachers begin to view literacy as a culturally situated practice, rather than a neutral set of skills. I also want them to recognize how power and perspective operate within texts and to learn to design curriculum that reflects the lived experiences of their students. These goals stand in stark contrast to NCTQ’s perspectives on teacher preparation and are commitments I have maintained in light of NCTQ’s critiques of my syllabus. The book I currently use in my course, Lorraine Wilson’s Reading to Live: Teaching Reading for Today’s World, is listed as “not acceptable” even as a supplemental text. Although the text utilizes critical literacy theory as a means for conceptualizing literacy instruction and incorporates countless instructional strategies for early reading (including phonics and phonemic awareness), I was told that I would have to remove it from the syllabus in order for our college to receive a favorable rating from NCTQ. Lastly, none of the syllabi that NCTQ offers as “exemplars” features authentic children’s literature as key texts in the course. In my literacy methods courses at UNM, I incorporate literature that addresses critical issues like immigration and racial justice and use these texts to inform our discussions regarding how social identities like race, class, and gender shape student experiences in schools. For example, in one of my courses we read Francisco Jimnez’s The Circuit, his 1997 memoir that documents his life as a migrant farmworker in California’s Central Valley. We use this text as a starting point for an inquiry into migrant labor and a means through which to discuss and model a range of reading and writing strategies. By ignoring the potential of children’s literature in literacy methods courses, NCTQ is neglecting a powerful motivating force for reading engagement Ñ one of the most essential for creating an ethos of lifelong reading among struggling students.

Reading for Christ?

In an effort to help university instructors (like me) improve our literacy courses, NCTQ includes selected resources on their website including exemplar syllabi in early reading instruction. Interestingly, when I visited NCTQ’s website in June of 2015, the featured syllabi came from only two institutions of higher education — Gordon College and Southern Methodist University — both of which are founded on Christian principles. In one of the highlighted courses, the primary course objective is listed as “Explain the Christian foundations of reading instruction.” On the Gordon College syllabus, there is no mention of meaning-making, comprehension, reader response, or students’ connections to a text. Instead, the syllabus focuses only on decoding, even though research indicates that a narrow focus on decoding in the early grades without more meaningful engagements with and across texts does not promote robust achievement in reading nor does it foster the development of lifelong readers.

The connection between Christianity and early reading instruction has a long and complicated history that can be understood, at least partly, through the controversy of whole language instruction. Literacy scholars have documented the ways in which policymakers sought to discredit whole language instruction due to its focus on the reader rather than the text. As Patrick Shannon (2007) argues, the notion that a single text can have a multitude of possible meanings and interpretations threatens the legitimacy of the Bible and the literal interpretation that many conservatives insist upon (p. 104). Over the past several decades these beliefs have been translated into policy and practice as conservative policymakers advocate for reading programs and pedagogical approaches that support deriving a single, unitary, and fixed meaning from a text, an approach that has become a hallmark of elementary reading instruction.

Time to Resist NCTQ

NCTQ is just one player on a much larger team devoted to privatizing, and perhaps eliminating, mainstream colleges of education in favor of alternative routes like Teach For America or newer incarnations of market-driven reform like the Relay Graduate School of Education and Aspire Teacher Residency. Moreover, the loss of academic freedom I currently face as a scholar parallels the ongoing attack on K-12 teacher autonomy throughout the United States. We can no longer take for granted that practitioners within university contexts are immune from efforts to undermine critical approaches to teaching and learning.

There are many examples of universities that have refused to comply with the NCTQ review by withholding program materials and publicly decrying the suspect evaluation methods. What is particularly striking about these forms of resistance is the ways in which universities and colleges have banded together in a show of solidarity. For example, colleges of education within the University of Alabama system have collectively refused to cooperate with NCTQ and worked collaboratively to deny the release of materials. Moreover, a consortium of teachers’ colleges in Wisconsin refused to participate in the review, citing that the NCTQ rating would not represent a fair or accurate assessment of their programs. In other instances, leaders and administrators within university systems have taken stands publicly to protect faculty members and teacher candidates from NCTQ’s demands. For example, the Georgia Board of Regents, which governs public universities in Georgia, has protected teacher educators at Georgia universities from complying with NCTQ.

These examples illustrate that colleges of education can effectively counter NCTQ. In particular, diverse institutions like the University of New Mexico have a responsibility to focus on language and culture as part of the teacher education curriculum and to serve as an example in the field of culturally responsive teacher preparation.

In my own efforts to resist NCTQ and preserve the commitments to diversity that my colleagues and I have cultivated at UNM, I refused to comply with the dean’s demands and did not change the readings or assignments on my syllabus nor did I speak with a consultant about how to make the syllabus reflect NCTQ’s requirements. Instead, I wrote two posts on Diane Ravitch’s widely read education blog sharing the experiences and concerns outlined in this article. Many friends and scholars within academia advised me not to write the blog post noting my vulnerability as an untenured, assistant professor. Interestingly, there was no reaction to these postings from my administration, though the NCTQ ratings are occasionally referenced at faculty meetings as something we need to consider as we design and enhance our courses. Once the blog posts were published, many K-12 teachers applauded my efforts, saying that it was about time university faculty took a stand against these reforms. Others pointed out the irony that university faculty seem to mount resistance only once reforms directly affect them, rather than acting in solidarity with their K-12 colleagues.

Preservice Teachers and Policy

Despite NCTQ’s proclivity for technical approaches to teaching and learning, the organization actually claims that its work is rooted in social justice. For example, in a response to the blog post I wrote, Arthur McKee, formerly the managing director of teacher preparation at NCTQ, responded by writing, “We are ourselves motivated by a sense of injustice, particularly the travesty that 30 percent of our students can’t read successfully by 4th grade when instructors well-versed in effective techniques could cut that percentage down to 10 percent or less.” Yet at the same time, NCTQ denies the importance of social justice-focused curricula and instead favors those approaches that will presumably lead to the most substantial gains in student test scores.

Given this tension, teacher candidates must begin to recognize that policies do not simply appear out of thin air but are created by certain people with specific intentions. Barbara Madeloni, then a teacher educator at UMass Amherst, together with students in the secondary certification program, collectively staged a resistance to the Teacher Performance Assessment (EdTPA), then in the pilot stages within Massachusetts, a move that illustrates how preservice teachers can be included in policy discussions as they begin to conceptualize what it means to be a teacher in the current political moment. Teachers’ voices are often absent from policy decisions, thus it remains critical to create conditions in which teacher candidates have the opportunity to make their voices heard.

Teacher education programs within diverse institutions like the University of New Mexico have the potential to serve as national models for what it means to conceptualize and enact culturally responsive instruction, especially in the fields of literacy and language learning, as we aim to meet the needs of a rapidly shifting K-12 student population. For example, an increasing number of teacher educators are positioning preservice teachers as community researchers, leveraging multicultural texts in their courses and foregrounding issues of justice even in courses that are conceptualized as “technical.” These examples provide rich counter-narratives to mainstream depictions of traditional teacher preparation as a failing enterprise and present images of what is possible when issues of diversity are privileged in teacher preparation programs. Inquiries into topics like immigration and racial justice, which have been central to my literacy methods courses, have revealed the urgency and necessity of engaging these topics with preservice teachers. Those of us deeply concerned with equity, social justice, and diversity can no longer afford to dismiss NCTQ — their reach is too broad and their message too insidious. The time to resist is now.

Katherine Crawford-Garrett is an assistant professor of teacher education at the University of New Mexico. She co-authored the article “Activism Is Good Teaching: Reclaiming the Profession” in the Winter 2015-16 issue of Rethinking Schools.

Illustrator Christiane Grauert’s work can be found at christiane-grauert.com.

References

Bos, Candace, and Sharon Vaughn. 2011. Strategies for Teaching Students with Learning and Behavior Problems (8th edition). Pearson.

Campano, Gerald. 2007. Immigrant Students and Literacy: Reading, Writing, and Remembering. Teachers College Press.

Coles, Gerald. 2003. Reading the Naked Truth: Literacy, Legislation, and Lies. Heinemann.

Dutro, Elizabeth. 2010. “What ‘Hard Times’ Means: Mandated Curricula, Class-Privileged Assumptions, and the Lives of Poor Children.” Research in the Teaching of English 44(3): 255-91.

Fuller, Edward. 2014. “Shaky Methods, Shaky Motives: A Critique of the National Council of Teacher Quality’s Review of Teacher Preparation Programs.” Journal of Teacher Education 65 (1): 63-77.

Gallagher, Kelly. 2009. Readicide: How Schools Are Killing Reading and What You Can Do About It. Stenhouse.

Gunning, Thomas. 2013. Assessing and Correcting Reading and Writing Difficulties (5th edition). Pearson.

Heath, Shirley Brice. 1983. Ways with Words: Language, Life, and Work in Communities and Classrooms. Cambridge University Press.

Gamse, Beth, et al. 2008. Reading First Impact Study Final Report. Institute of Education Sciences.

Jimnez, Francisco. 1997. The Circuit: Stories from the Life of a Migrant Child. University of New Mexico Press.

Jones, Stephanie. 2006. Girls, Social Class, and Literacy: What Teachers Can Do to Make a Difference. Heinemann.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. 2000. Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-Based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and Its Implications for Reading Instruction. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Ravitch, Diane. 2010. The Death and Life of the Great American School System: How Testing and Choice Are Undermining Education. Basic Books.

Roche Jr., Walter F. 2006. “Bush’s Family Profits from ‘No Child’ Act.” Los Angeles Times, Oct. 22.

Schneider, Mercedes. 2014. A Chronicle of Echoes: Who’s Who in the Implosion of American Public Education. Information Age Publishing.

Shannon, Patrick. 2007. Reading Against Democracy: The Broken Promises of Reading Instruction. Heinemann.

Wilson, Lorraine. 2002. Reading to Live: Teaching Reading for Today’s World. Heinemann.

Wolter, Deborah. 2015. Reading Upside Down: Identifying and Addressing Opportunity Gaps in Literacy Instruction. Teacher’s College Press.

Woodson, Jacqueline. 2003. Locomotion. Puffin Books.

Yatvin, Joanne. 2002. “Babes in the Woods: The Wanderings of the National Reading Panel.” Big Brother and the National Reading Curriculum: How Ideology Trumped Evidence. Heinemann.