“I Saw Eyes Begin to Widen”

Joys, Pitfalls, and Dilemmas in Using Role Play in the Classroom

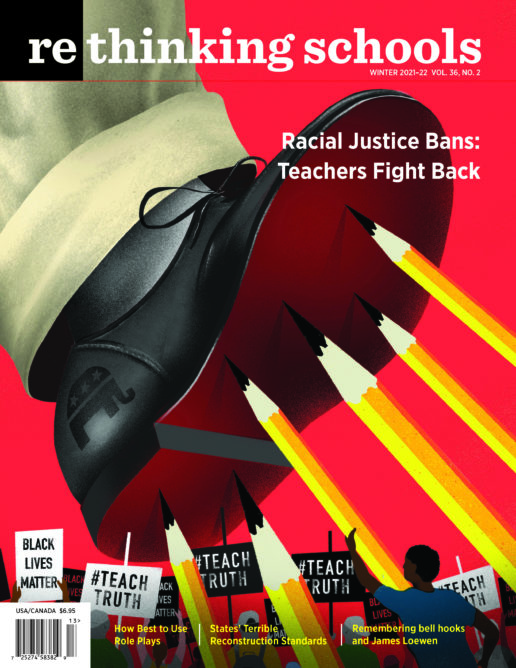

Illustrator: Simone Shin

One of the key challenges in teaching students about the world is finding strategies that show — rather than just tell about — social dynamics.

Students learn best when they are fully present, involved, facing dilemmas, sorting through choices, imagining alternatives. And this is also an equity issue. No doubt, some students may thrive in a lecture- and text-dense curriculum, but many will not. A show-don’t-tell curriculum rich with role plays can engage all students by bringing social dynamics to life in the classroom. As Kevin Sparks, a middle school teacher in Oakland, California, wrote to us about his classroom experience: Role plays “give every student an opportunity to participate in some way. Even the students who are normally shy about speaking in front of classmates are at least engaged in the dialogue and writing notes furiously.”

Rethinking Schools publications and the Zinn Education Project feature lessons that reveal key aspects of U.S. history — lessons that we hope elicit intense student engagement. Some of these activities are role plays — trials that urge students to reflect on ethical questions about responsibility for injustice, like “Deportations on Trial” (bit.ly/DeportationsOnTrial), about the mass expulsion of Mexican Americans during the Great Depression, or “Hunger on Trial” (bit.ly/HungerOnTrial), about the cause of the Great Famine in Ireland; single-group role plays that pose critical strategic questions for those seeking a more just society, like “Teaching SNCC” (bit.ly/SNCCRolePlay) or “Reconstructing the South” (bit.ly/ReconstructingTheSouthRolePlay); mixer role plays that surface diverse perspectives on key organizations or events, like the Black Panther Party (bit.ly/BPPMixer) or the struggle for voting rights (bit.ly/VotingRightsRolePlay); multiple-group role plays that help students recognize the social foundations of conflicts around the Dakota Access Pipeline (bit.ly/DAPLRolePlay), or the shaping of the New Deal (bit.ly/NewDealRolePlay) or role plays that allow students to discover commonalities and build solidarity, like the La Vía Campesina role play about food sovereignty (bit.ly/FoodSovereigntyRolePlay).

This article offers some cautions and guidance about teaching role plays, especially in these politically contentious times. We also describe concerns and suggestions teachers have shared with us over the last several years. What is offered here is not final, but an invitation to join us in the ongoing dialogue about the design and implementation of role plays.

Students learn best when they are fully present, involved, facing dilemmas, sorting through choices, imagining alternatives.

Role plays can be exhilarating, nurturing both insight and activism. San Francisco language arts teacher Jennifer Stangland describes her experiences using a mixer role play on housing segregation:

As soon as students received and began reading their roles for the lesson “How Red Lines Built White Wealth: A Lesson on Housing Segregation in the 20th Century,” I saw eyes begin to widen. Frantic highlighting and slight gasps of shock, along with giggles of disbelief, began to echo through the classroom. This is when you know students are about to learn something, and learn something that matters. Minutes later, the entire class was on their feet, moving to find someone they could share their “story” with.

At the end of the day, the entire class seemed to leave the room with a newfound sentiment of “now this makes sense.” Now it makes sense as to why the results of the blatant segregation from decades and decades ago still exist. Now it makes sense as to why I live where I live, and you live where you live. Now it makes sense as to why the money resides in certain homes, but not others. And the question that now exists in students’ minds is not “why,” but rather “how” — “How do we change things? How do we learn more? And how do we make a difference?”

Cristina Tosto, a U.S. history teacher in Gulfport, Mississippi, describes her experience with our role play on the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (bit.ly/SNCCRolePlay), in which students attempt to take on the persona of a SNCC activist:

I wish people could see how the kids were really strategizing and getting into their roles as SNCC members. It was so encouraging to me as a teacher to see my students understand the grassroots organizing of the Civil Rights Movement. However, it was even more rewarding to watch them engage with the material in a social, emotional, and critical way. They are not only learning history, they are learning skills that can be applied to real-life scenarios.

Laura Farrelly, a social studies teacher from Eugene, Oregon, described how students’ excitement from a role play can transform into activism:

My students were completely engaged in The People vs. Columbus trial we held about the massacre of the Taíno people. . . . They were so outraged that Columbus Day is a federal holiday that I suggested we send letters to the editors of local newspapers and our city council. They were so excited. Most of the students chose to send letters. When a student’s letter was published the next day advocating for our city to celebrate Indigenous People’s Day, the students who had not yet sent letters immediately began to write their own. It was a powerful lesson in civics, especially since my students are disenfranchised and feel like they don’t have power to effect change politically.

However, like any classroom strategy, role plays can be misused and poorly designed, as a number of recent stories illustrate. An educator in Bronxville, New York, asked Black students to put on imaginary shackles while white students “bid” on them; a school in Tennessee invited students to dress as Nazis and give the Nazi salute in the hallways. In this issue of Rethinking Schools (p. 34), Azizah Curry describes a “role play” in which students “became performers in a dangerous mockery of history.” It was an activity allegedly about Rosa Parks and her defiance that led to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, but whose aims were so ill-formed that stereotype and hurt were guaranteed. These are awful activities, failing by every pedagogical and curricular measure, and we join those who have decried them.

So what do we mean — and not mean — when we say “role play”? The term “role play” can connote both that it is a performance, as in a play, as well as that it is playful, fun. These turn out to be unfortunate associations, especially when they are connected with classroom lessons that may deal with genocide, enslavement, deportations, or other violent and disturbing content. Although it is true that we ask students to take on a “role” — that is, the perspective and interests of someone from another time or social location — it is an intellectual endeavor, not a performative one. Sometimes our role plays are confused with historical reenactments. The Zinn Education Project does not feature any activity that attempts to “recreate traumatic experiences,” in the words of Hasan Kwame Jeffries, professor at Ohio State University. Nonetheless, because we find ourselves so often having to explain what we mean and don’t mean by “role play,” we invite readers to join us in considering how to more accurately name these activities (bit.ly/RolePlaysFeedback).

The Zinn Education Project strives to make sure that all the curriculum we share, including role plays, meets an ambitious set of goals. It should:

• Explain complex social phenomena like white supremacy, settler colonialism, social class divisions and wealth inequality, or environmental exploitation.

• Focus on events, groups, and individuals too often erased, minimized, or oversimplified in corporate curricula, especially movements and individuals who have acted for justice.

• Increase students’ capacity to act for justice by:

a) Growing their imaginative capabilities, the cornerstone of empathy and solidarity.

b) Exploring how systems affect people’s choices, analysis necessary to solve seemingly intractable problems.

c) Allowing time and space for participatory, problem-solving pedagogy.

d) Thwarting cynicism and resignation by emphasizing activism and resistance, and the recognition that at all points in history, there are choices; nothing is inevitable.

Concerns About Role Plays

Nonetheless, over the last several years, concerns have been surfaced by teachers in our network and some of our own team members about some of the role play strategies described in Rethinking Schools and the Zinn Education Project. In some instances, teachers have raised objections about the pedagogy of role play itself.

One area of concern is asking students to step into the role of an oppressor — figures like Columbus, an enslaver, or J. Edgar Hoover. Some teachers have told us that by asking students to take on the personas of oppressors, they fear that students may come dangerously close to building identification with them. And this is especially true in an era when Donald Trump sought to make white supremacy respectable, which, not surprisingly, has leaked into classrooms across the country. Others have said that voicing oppressive views can itself be harmful, both for the speakers and listeners. The corollary to the discomfort around oppressor roles is concern about “victim” roles — asking students to imagine the experiences, past and present, of those who have been removed from their land, enslaved, and exploited. Some have asked if such a classroom activity may trigger a trauma response in their students, particularly students of color. Teachers who have reached out with these concerns have also expressed uneasiness about the underlying premise of many of these activities: that students can and should imagine into and write and talk from the perspective of people different from them. We have heard particular discomfort about the idea of asking white students or students of privilege to speak from the standpoint of a person of color or other oppressed people in a role play.

It is not our intent here to dismiss or to argue with these important concerns. We find ourselves in a period when we too are wrestling with what it means to teach effectively for social justice and we are revising the structure of a number of the role plays we offer. Here, we hope to distill some of the reasons to consider using and adapting role plays, but to offer some cautions too.

No Neutral Classrooms

Role plays about structural racism, genocide, or exploitation and oppression are not something to ever do “cold” with students during the first week of school, nor something to leave with a substitute teacher while we are away from class. A role play is not a one-off or stand-alone “enrichment” activity. Before tackling a role play about serious content, we want our classroom to have already established norms and a burgeoning sense of community. Students’ respectful, historically grounded role-taking must happen in a classroom where students are used to talking and thinking explicitly about race and justice. Some teachers have told us that they don’t do role plays early in the year, but only after laying significant groundwork — discussion of historical oppression and social identities. Students need to understand that any role play is embedded in a broader curricular project to explain the origins and persistence of social inequality in the United States, and to equip students to see themselves as potential change makers.

For role plays to be successful, it is important that students understand that we are in fact not neutral; when we teach a role play that includes people in history who exploited and oppressed others, we are not engaging in a “both sides” curriculum.

Some teachers express pride about their “neutrality” in class. Through the years, we have heard variations of the comment: “At the end of the year, I don’t want my students to know my politics.” But for role plays to be successful, it is important that students understand that we are in fact not neutral; when we teach a role play that includes people in history who exploited and oppressed others, we are not engaging in a “both sides” curriculum. Our teaching joins an effort to critique social inequality and to explore alternatives. We take sides in favor of those who work for greater equality, who challenge oppression based on race, social class, nationality, language, gender, religion, disability.

Any time a role play includes social groups whose livelihoods, wealth, or privilege depend on various forms of exploitation, students will portray characters who articulate justifications for these abuses. However, for students to arrive at insights about the nature of oppression, it is essential that they recognize that they are not being asked to find legitimacy in exploitative ideas, but to recognize the circumstances that give rise to them. One of the “habits of mind” of any social studies class is for students to reflect on the relationship between social conditions and consciousness. We might say at the beginning of a role play, for example, “Some of you will express ideas that you don’t believe and find repugnant. We are not doing this role play to suggest that ideas expressed here by different social groups are of equal worth, but to try to understand what motivated people to think and act the way they did.”

For example, in the role play on the origins of U.S. involvement in Vietnam, students representing the French government will justify the colonization of Vietnam. If we thought that students would end up believing that colonial ideas and anti-colonial ideas were equally valid, we would not teach the role play; however, the role play’s definitive takeaway is that at the end of World War II, the United States sided not with “freedom and democracy,” but with racism and colonialism, by supporting the French reconquest of Vietnam. In these kinds of roles, we hope students come to see that it doesn’t take being “evil,” “bad,” or even exceptionally bigoted to buy into colonialism or the class incentives of labor exploitation. When oppression is structural, it merely requires following the logic of a system. If we lead students to believe that only “bad” people (or countries) are racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, or destructive to the environment, it becomes easy to make oppression something other people do, not something of which we are all capable, and for which we all have a role in recognizing, disrupting, and resisting. These are takeaways we encourage teachers to raise with their students as part of a thorough follow-up discussion.

We have heard from some teachers who, suspecting that their students might not navigate a role play thoughtfully and with care, chose to pursue another pedagogical path altogether; others have adapted role plays — removing a role or changing the tense from first person to third person — to feel less potentially harmful. We encourage this kind of careful consideration of the particular context in which each of us teaches. The social composition of our classes should always frame our pedagogical choices. There are no cookie-cutter curricula and we are eager to hear how — and why — educators tailor our materials for their own classrooms.

The Power of Imaginative Role-Taking

Many of our role plays focus on hidden histories of resistance — with all the roles representing people who have fought for voting rights (bit.ly/VotingRightsRolePlay) or climate justice (bit.ly/ClimateJusticeMixer), for example. Our role plays sometimes include both perpetrators and victims of injustice, and the activists and everyday people who resisted — and resist — oppressive systems and policies. It is critical that educators do all they can to minimize the possibility of turning what should be an elucidating intellectual endeavor into harmful caricature or performance.

Prior to participating in a role play, we caution students that this activity will not involve wearing costumes, speaking in accents, or adopting stereotypical mannerisms. The goal is not to attempt to “act” like a character as one would in a play, but to understand and try to surface the character’s thinking and motivations, as a kind of social and historical investigation. We might say to students: “You carry real people’s stories in class today — people who may have suffered or been harmed. Please approach them with the dignity they deserve.”

When leading these activities, we never force students to adopt a specific role; if a student says they don’t feel comfortable in one role, we simply let them choose another. And we make it clear to students at the outset that if assigned the role of an oppressed group (an enslaved person, a deportee, an incarcerated Japanese American), they will not be asked to act out a traumatic experience. Rather, they will be asked to imagine and give voice to oppressed people’s resistance, agency, and understanding of the systems and forces that defined their predicament. Role plays — like persona poems, interior monologues, or really any form of literature — are invitations to students to try to imagine others’ points of view. Understanding across difference, studying and imagining the world as others experience it, is the foundation of solidarity. If we cannot imagine into someone else’s experience, it becomes much harder to work toward a just future for us all.

That said, we have heard from teachers who choose not to ask their students to speak in the voice of someone from another social group. Some adapt activities so that students speak in third person; rather than take on the persona themselves, students predict how that individual might have stood on a particular issue. As with all social justice work these days, teachers are trying to revise and invent pedagogical models that best address the challenges we face and the needs of all of our students.

Some educators have asked if it is appropriate to ask white students to put themselves in the position of someone of a different race. By speaking in another’s voice, might white students wrongly believe that they fully grasp “what it feels like” to be in the position of an oppressed group? Are white students capable of representing the ideas and perspectives of other races without resorting to hurtful and inaccurate caricature and stereotyping? Teachers need to answer this question for their own situation. Yes, it is impossible for white kids in particular to accurately imagine themselves as an enslaved person or a member of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe. But not to ask them to try is to reify “race” in a problematic way. It paradoxically acquiesces to the racist ideas social justice educators seek to undermine: that race is essential and fixed. We are not asking students to “be” African American or to “be” Native. We are asking them to undertake an intellectual challenge and a moral imperative: to attempt to imagine into the historically specific circumstances of a group of people at a moment in time. One purpose of social justice education is to show students that these categories of difference were created through oppressive relations, and can therefore be dismantled through different, more just relations. Acting as though race is some unbridgeable divide that can never be crossed does not help with that project.

After the Role Play

Adequate reflection and processing of the experience of the role play is not incidental, but fundamental. We always seek to provide plenty of time and space for students to step out of their roles and reflect on their experience. What did they notice? What new understandings were gained? What new questions emerged? This step is perhaps most critical for students who take on roles of figures with whom they may disagree or whose positions they abhor. Students need a chance to distance themselves from the circumstances of a role play, to speak in their own voice, and against the very arguments their character expressed in the activity. The post-role play debrief is also a time where students get a chance to hear each other’s “real” opinions and build powerful collective analyses of some of our world’s most intractable problems — racism, inequality, environmental destruction.

Other Curricular Dangers

As we have suggested, role plays can be joyful and enlightening, and they can be dangerous. Done poorly, they can be hurtful. They can reinforce stereotypes. They need to be approached with caution. But let us emphasize this: The traditional, non-role play, non-participatory curriculum that ignores injustice is also dangerous. To pick just one small example, a typical textbook like Holt McDougal’s The Americans offers seemingly innocuous activities like a chart on the so-called Compromise of 1850: “Suggest that students use both the text and the chart to recommend an S (South) or N (North) for each term to show which side benefited from it.” This is a nonsensical and offensive assignment that erases the humanity and agency of Black people, who “benefited” from none of these compromises between white elites, all of which aimed to prolong slavery. This kind of teaching is both dangerous and boring — just one small instance of alienation that leads many students to disengage from school. As Linda Christensen points out in a Rethinking Schools article about the dangers of a push-out curriculum: “The school-to-prison pipeline doesn’t just begin with cops in the hallways and zero tolerance discipline policies. It begins when we fail to create a curriculum and a pedagogy that connects with students, that takes them seriously as intellectuals, that lets students know we care about them, that gives them the chance to channel their pain and defiance in productive ways.”

Of course, this is not to suggest that to abandon role plays requires us to abandon critical teaching. All of us can think of powerful learning experiences we’ve had that did not involve taking on a role. We are emphasizing that a participatory, show-don’t-tell curriculum is a pedagogical strategy worth keeping and refining.

Share Your Stories

Today, social movements are rightly demanding that we examine every nook and cranny of our world to make sure that people are fully represented, that no one’s life is treated as disposable. We need a similar reckoning in our curriculum. Way back in 1994, Rethinking Schools articulated the outlines of a social justice curriculum in the book Rethinking Our Classrooms. Editors insisted that our teaching should be grounded in the lives of our students; critical, multicultural, anti-racist, pro-justice; participatory, experiential; hopeful, joyful, kind, visionary; activist; academically rigorous; culturally sensitive.

These strike us as valuable principles to guide our teaching today. Role plays, done well, can embody all these elements.

But the conversation is ongoing. We depend on your feedback. More than 140,000 educators have signed up at the Zinn Education Project, coordinated by Rethinking Schools and Teaching for Change, to access our materials, and thousands of teachers, in very different settings, have used our lessons. Please share your teaching stories (bit.ly/RolePlaysFeedback): How have you adapted our lessons? When have you encountered difficulties? When have they gone well?

Rethinking Schools was born in 1986. Teaching for Change was established in 1982, first as the Network of Educators’ Committees on Central America. This work is ongoing. Thank you for being part of our community — a movement of social justice educators, remaking our classrooms, remaking society.

If you want to get more articles like this one — and to support independent journalism — subscribe now to Rethinking Schools magazine.