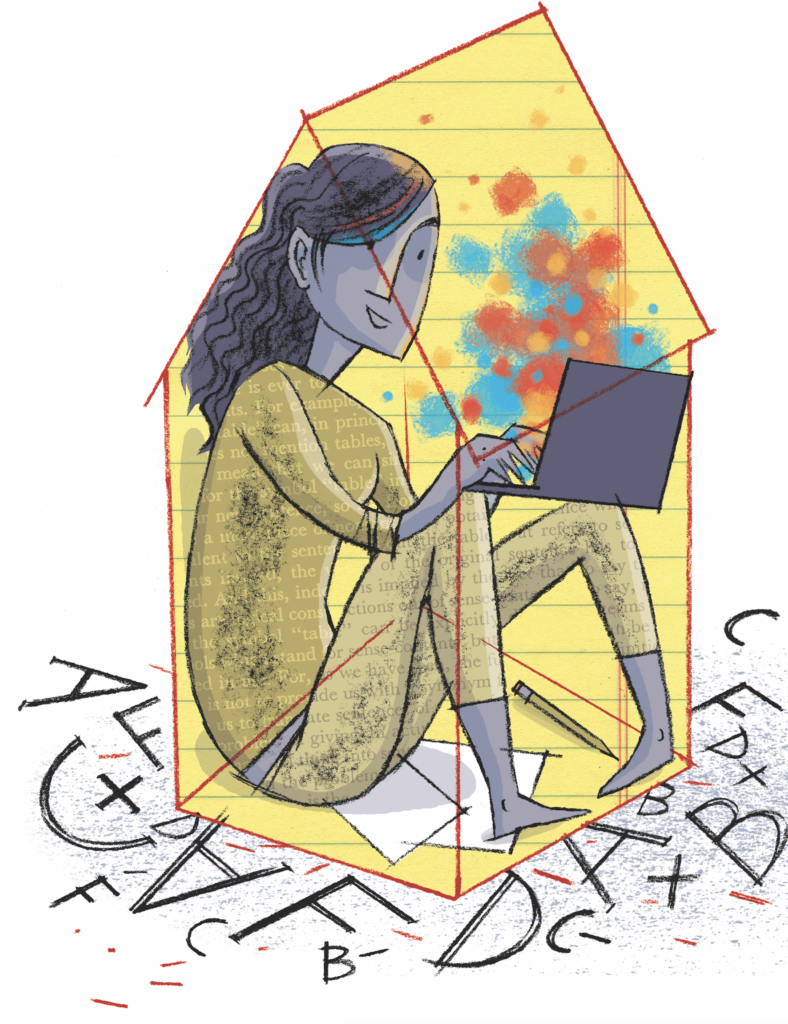

I Hate the Pandemic, but I’m Grateful to Be Rid of Grades

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

I hate this pandemic. But, I am also humbled by the little bundle of destructive protein that has put our American way of doing things on pause. And kind of like when you pause a movie, on that shaky, jittery screen, you notice things that otherwise would have passed you by. You lean in closer, looking between the protagonist’s feet, or in the triangle of their elbow, and you see the broken things in the background. In a movie, it’s an errant water bottle left on set, a guy with a baseball cap on during a medieval joust, a boom mic hanging in the corner.

In a pandemic, you see the broken healthcare system, the bruised faces of nurses and doctors as they wear the wrong protective gear. You see the gouging and manipulation of the tech companies, who used to swear that the internet was an elective commodity. You see that, all this time, our city could have housed the homeless, instead of shrugging their shoulders and leaving them out in the cold.

And I, as a teacher, can see the gaping, open wounds in the education system on full display, because the movie didn’t just move into the next frame. It’s on pause, and I have a high-definition TV.

One of the most glaring things staring back at me is our grading system. I’ve never liked grades, but I begrudgingly put them in each quarter because we have been conditioned to believe that they are the way to show progress and understanding. I’ve asked why we need to do this, especially in middle school, where students will be shuffled into the next grade, whether or not we’ve humiliated them with a failing grade.

The answer has always been: “We need to prepare them for high school.” And the movie plays on. Even when I’ve tried to shift things into a feedback model, with students making portfolios to showcase their work, it’s the parents eager to have me press play on the old, shitty way of doing things. I kept perpetuating a system that I knew was broken.

Traditional grades have never served students well; they don’t show a student’s ability to think, write, and problem-solve. They just show which kids have the luxury of finishing their homework at home or on time. They show which students have the privilege of tutoring, with the flexibility to ask their parents for a ride before or after school so they can get one-on-one help from their teachers. They show which students are steeped in the language and culture that the U.S. A–F grading system favors, which affects our students of color disproportionately. As a daughter of immigrant parents from Mexico, who worked multiple jobs, my family could not afford zoo camps, yearlong memberships to a science museum, or vacations to Europe. (Our first family vacation took place when I was 28; long past when I could use it to write an essay for a standardized test.) Traditional grades do nothing but force the students who do not have privilege to work even harder to earn that A. And when they do, their hard work is often used to highlight them as the “exception” to the stereotype.

Now, during the pandemic, I not only can see the problem, I can dart into the projection room and change the frame. My district has said that instead of the traditional A–F grades, we will give students a “Pass” or “No Grade” this semester.

I am connecting with my students in a way I never have before. For the first time, I don’t worry about grading students’ pieces against standards that reward stale, stilted, and standardized writing. I hear students’ voices ring loud and clear, pouring their hearts onto the page.

I’m not getting bombarded with “Is this enough to get an A?” or “How much do I need to do to get a four?”

I am now a teacher who coaches, instead of a boss who demands a certain number of sentences or paragraphs, dangling that grade A paycheck just out of arm’s reach. I am asked to give feedback. “Can you read my first paragraph?” “Can I write directly to the virus?” “Do you think if I say life before was a roller coaster, and now it’s a carousel, people would get it?” These are some of the questions I get. Instead of plugging grades robotically into the Synergy grading system, I write detailed feedback for each student’s piece of writing and watch it bloom into a beautiful narrative. I feel their grief, anger, and hope as they describe missing graduations and family vacations. They write how they miss hugging their friends, feeling the beach sand between their toes, crossing the finish line after a grueling track meet, and they wonder how this pandemic will shape them and the world around them.

I’ve decided all of my students are going to pass. Because living through a damn pandemic is passing.

Because, as they grieve and lament their freedom to be 14-year-olds eating garbage at the mall with their friends, many still write me to check in. That’s passing.

Because so many are living with parents without jobs, or living with the added responsibility of parenting their own siblings. That’s passing.

Because in the midst of all of this, they ask me what they can read to escape this terrible plot twist in the movie of their lives. That’s passing.

Because I have received poems and ponderings, written in the middle of the afternoon, or in the early gauzy light of the morning, or in the lonely darkness of the night, and they are beautiful. That’s passing.

Although I miss seeing my students every day in the classroom, I have loved watching them become writers.

I want to take the film we’ve become used to playing over and over again, yank it off the projector, and smash it. Not just for the pandemic, but for always. This pandemic has shown me in brilliant Technicolor that students need feedback, not grades.

Subscribe to Rethinking Schools magazine at rethinkingschools.org/subscribe.