“I Don’t Like China or Chinese People Because They Started This Quarantine”

The History of Anti-Chinese Racism and Disease in the United States

On April 20, 2020, blogger LittleGrayThread made a Facebook post of a note her daughter had written. She reported that in a Zoom class meeting, one of her daughter’s 2nd-grade classmates said, “I don’t like China or Chinese people because they started this quarantine.” The racist statement rightfully upset the blogger’s Chinese American daughter, who wrote a response, which read:

When we did the Zoom meeting, someone said that he doesn’t like China and Chinese people. This made me feel sad because he was my friend and I’m Chinese. I hope he will stop telling people that because it’s mean and wrong. It’s wrong because he doesn’t know what he is saying. No one knows how the virus started for sure. When you say that you don’t like Chinese people you’re saying that you do not like me. I did not start this virus. Thank you for being my friend.

I love her written response to the racism she experienced. But as an educator and parent of a 4th grader, reading about what happened to LittleGrayThread’s daughter was disheartening and maddening, yet sadly unsurprising.

This winter, as the coronavirus made its way from China to the United States, many of us knew what would happen: Racists in this country would confuse the coronavirus’s origins in China with Chinese people around the world. Then they would turn their racist vitriol toward anyone who “looked” Asian to them, because to them we all look alike.

This winter, as the coronavirus made its way from China to the United States, many of us knew what would happen: Racists in this country would confuse the coronavirus’s origins in China with Chinese people around the world. Then they would turn their racist vitriol toward anyone who “looked” Asian to them, because to them we all look alike.

Fear of the virus soon translated into patrons avoiding Chinese and Asian American restaurants before the virus took hold in the United States. As it spread, so did racist attacks. Reports of Asian Americans being spat upon, screamed at, told to “go back to China,” being avoided by non-Asians, and told “don’t bring that Chink virus here” started to appear across social media and in the news.

In an April 23 report, the Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center documented almost 1,500 incidents of anti-Asian American harassment and assault since March 19. Asian American women were 2.3 times more likely to be harassed than Asian American men.

All this came on the heels of racist dog whistling by President Trump, who has regularly referred to the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus.”

We have to oppose this anti-Asian American racism, but we also have to teach our students how we got here. Trump’s “Chinese Virus” and other attacks on Asian Americans recall similar attacks from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Then, too, viruses were conflated with the humans who were afflicted by them, and then used to attack those people already suffering from racist discrimination. When students look historically at the intersection of race and disease they can better understand the white supremacy that has been revealed by the COVID-19 response.

Orientalism and Anti-Asian American Racism

To understand today’s anti-Chinese American and anti-Asian American racism, we need to look at “Orientalism.” Historically, European colonizers framed much of their world in terms of the West — the Occident — versus the East — the Orient. For them, the Occident was cultured, civilized, trustworthy, pure, and godly, while the Orient was barbaric, uncivilized, heathen, untrustworthy, and culturally and morally depraved — providing justification for European rulers’ imperial ambitions. Orientalists viewed Chinese as “Mongolian hordes” who threatened European culture and values.

As “Orientals” entering U.S. territories colonized by white settlers, Chinese and other Asian American communities were never trusted as legitimate members of society. Whites often saw them as interlopers, temporary labor, outsiders, and a cultural “other.” This is the ideological basis of the “Yellow Peril”: In response to economic or political crisis, Asian and Asian American communities are framed as a non-Western threat to “American” values and supremacy.

In 1848, there were about 325 Chinese immigrants in the continental United States; by 1880, 300,000 Chinese had immigrated to the country. Although some came in response to the California gold rush, most worked on the transcontinental railroad. White railroad barons paid Chinese railroad workers lower wages and often gave them the most dangerous jobs (like dynamiting mountains in preparation for tracks).

White racism deeply influenced the living conditions in the Chinatown neighborhoods where immigrants were forced to settle. White landlords often mistreated Chinese American tenants and kept their housing in disrepair with no fear of reprisal. Coupled with inconsistent city infrastructure for sewage systems and clean water, this contributed to the substandard living conditions and general squalor that helped spread disease.

White racism deeply influenced the living conditions in the Chinatown neighborhoods where immigrants were forced to settle.

Popular media painted Chinatowns as seedy, dirty, heathen, dangerous, full of “vices” like gambling, drugs, and prostitution, and full of similarly dirty and dangerous people. Likewise, whites saw Chinatown neighborhoods as uncivilized, “foreign” spaces to be controlled by Western authorities.

These racist tropes laid the groundwork for equating Chinese Americans with disease — which first happened more than 100 years ago, and continues today.

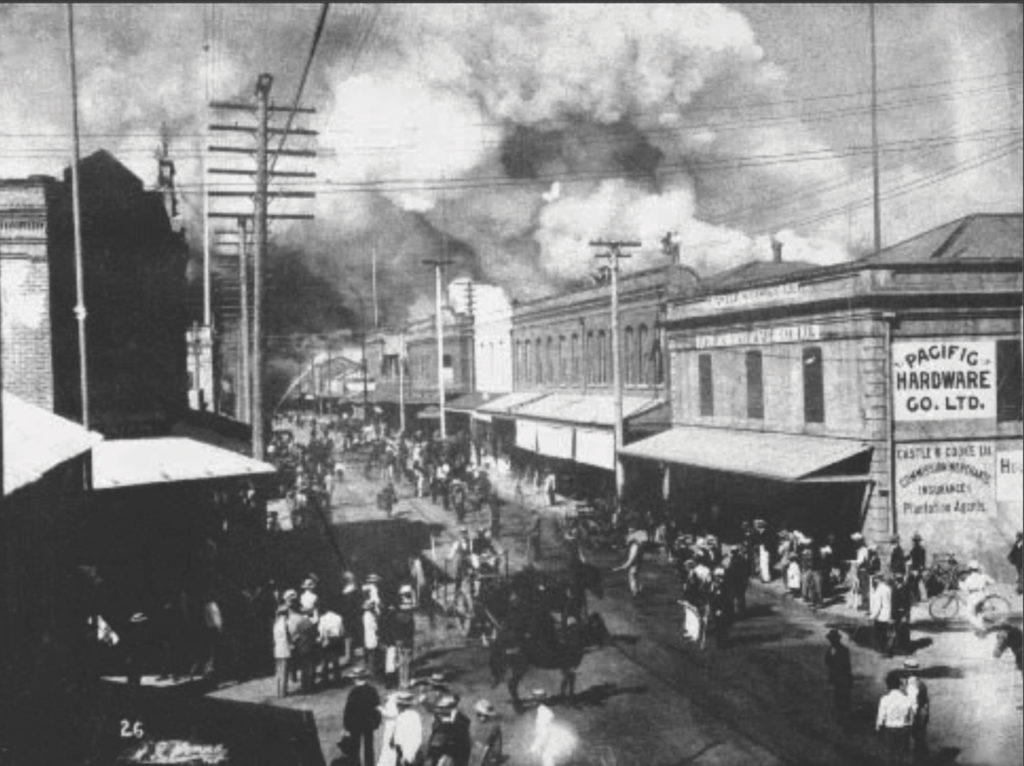

The 1899–1900 Quarantines and Burning of Honolulu’s Chinatown

On Dec. 12, 1899, health officials confirmed a single case of bubonic plague in Honolulu’s Chinatown. The so-called President Dole — who came to power when a gang of white businessmen and missionaries overthrew Queen Liliuokalani, Hawai’i’s Indigenous sovereign — declared a state of emergency. Honolulu’s Chinatown — 14 square blocks, around 10,000 people — was quarantined the next day. Officials painted lines around Chinatown and placed guardsmen on 24-hour patrol.

White authorities subjected Honolulu’s Chinatown population — mostly Chinese* but also roughly 1,500 Japanese and 1,000 Native Hawaiians — to daily inspections of their homes and bodies to check for signs of plague. Residents felt the intrusion of invasive bodily inspections by white inspectors of the “Citizens’ Sanitary Commission,” raising concerns about petty theft, racial harassment, and even attempted rape by inspectors.

(*Note: I refer to the Chinese in Hawai’i at this time as “Chinese” as opposed to “Chinese American” because, even though the white businessmen and missionaries had forcibly taken control of the Hawaiian government with the aid of the U.S. Marines, technically Hawai’i had not yet become a territory of the United States. So, the term “Chinese American” would be historically incorrect.)

Honolulu Chinese also pointed out the racist boundaries of the quarantine zone. The Chinese-owned City Mill was included in the quarantine, but the white-owned Honolulu Iron Works next door was excluded — forming a white quarantine-free peninsula extending into Chinatown.

A native Hawaiian newspaper, Ke Aloha Aina, pointed out that the Chinatown residents weren’t to blame for the conditions there:

The Japanese and Chinese are not the unclean ones who are spreading the plague in the city. . . . Instead, it is the large land owners who rent units on a large-scale profit. These are people such as Samuel Damon, Dillingham, Keoni Kolopana, and some others who sit and collect huge monthly and annual profits.

White officials lifted the first Honolulu Chinatown quarantine after several days. However, when several more people died of plague, officials placed Chinatown under quarantine again and proposed a controlled burning of individual plague-infected buildings.

The Honolulu Chinese protested the burning plans, posting fliers and making death threats against the Board of Health and any Chinese officials who cooperated. Chinese property owners wrote letters, and community leaders petitioned authorities.

Then, on Jan. 14, 1900, a white woman who lived in a wealthy Honolulu suburb came down with the plague. Her death shocked the white community — who mistakenly thought whites couldn’t catch the plague, and several white newspapers began to advocate for leaders to burn down Chinatown.

The wholesale burning of Honolulu’s Chinatown never became policy, but whites who advocated its eradication soon got their wish.

On Jan. 20, 1900, during a controlled burn of an infected Chinatown building, the winds picked up, spreading the fire. The community of Chinese, Japanese, and Hawaiians worked together with the fire department to regain control, but the inferno spread through Chinatown. The fire wiped out 25 city blocks and displaced at least 6,000 residents — most of whom were relocated to detention camps.

Less than three months later, bubonic plague was found in San Francisco’s Chinatown, and the response there was as racist as it was draconian.

The Quarantines of San Francisco Chinatown

On March 6, 1900, there was a suspected death from bubonic plague in San Francisco’s Chinatown, and the Board of Health cordoned off Chinatown. More than 35 police officers were posted around 12 square blocks. White authorities blocked traffic, limiting the movement of the 25,000 residents — mostly Chinese American, but also more than 1,000 Japanese Americans.

However, whites were allowed to leave because, like in Hawai’i, whites believed they couldn’t get the disease.

The San Francisco Chinese Americans resisted this selective quarantine. Members of the community gathered to protest, and the Chinese Consul-General of San Francisco called the “Blockade of Chinatown” racist.

Mayor James D. Phelan countered that the quarantine was necessary because Chinese people were a “constant threat to public health.”

The Chinese American community protests overwhelmed white officials, and less than three days after it began, the Board of Health ended the quarantine.

The Chinese American community protests overwhelmed white officials, and less than three days after it began, the Board of Health ended the quarantine.

With a cluster of plague deaths near the end of April, the federal government directed local officials to administer an experimental vaccine, one known to have severe side effects, to the Chinatown population.

By mid-May, large crowds of Chinese Americans protested, noting the vaccine’s harsh effects. On the night before the forced vaccinations, fliers posted around San Francisco’s Chinatown announced resistance:

It is hard to go against an angry mass of people. The doctors are about to compel our Chinese people to be inoculated. This action will involve the lives of us all who live in the city. Tomorrow . . . all business houses large or small must be closed and wait until this unjust action settled before anyone be allowed to resume their business. If any disobey this we will unite and put an everlasting boycott on them. Don’t say that you have not been warned at first.

When the mostly white doctors and health officials came to Chinatown to begin the forced vaccination program, they found businesses closed and residents leaving the area. In the days that followed, Chinese American protesters rallied against those Chinese Americans who they believed were cooperating with the vaccination program.

Health officials also directed the railroad companies to deny Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans passage on trains leaving the city if they could not prove vaccination.

A Chinese American merchant filed a complaint with the federal court. Federal Judge William W. Morrow invalidated the travel ban, saying that it violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. He ruled that the travel restrictions were “boldly directed against the Asiatic or Mongolian race as a class, without regard to the previous condition, habits, exposure to disease, or residence of the individual.”

White health officials quarantined San Francisco’s Chinatown again after more Chinese Americans died of plague. On May 30, 53 police officers patrolled the lines of this new racial quarantine. A San Francisco Chronicle reporter observed that in the “careful discrimination in fixing the line of embargo, not one Caucasian doing business on the outer rim of the alleged infected district is affected. . . . Their Asiatic neighbors, however, are imprisoned within the lines.”

The editors of San Francisco Call demanded that Chinatown be burned:

In no city in the civilized world is there a slum more foul or more menacing than that which now threatens us with the Asiatic plague. . . . So long as it stands so long will there be a menace of the appearance in San Francisco of every form of disease, plague and pestilence which Asiatic filth and vice generate. The only way to get rid of that menace is to eradicate Chinatown from the city. . . . Clear the foul spot from San Francisco and give the debris to the flames.

The Board of Health added barbed wire to the cordon and doubled the patrolling police force.

In court, Chinese American leaders again complained about their treatment. Judge Morrow called the Chinatown quarantine the “administration of a law ‘with an evil eye and an unequal hand.’” Again, drawing upon the 14th Amendment, he issued an injunction lifting the second quarantine of San Francisco’s Chinatown.

A Moment to Teach About Racism

Given our country’s history of racist Orientalism and anti-Asian American violence, it is easy to see how here in the United States the recent outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has been so effortlessly and predictably mapped onto the Chinese and other Asian American communities. As students reflect on the myriad effects of the pandemic, let’s help them see how agendas of racism and xenophobia have happened throughout our history. No doubt, fear of infection — whether from bubonic plague or COVID-19 — is legitimate. But time and again, epidemics have been used to attack Chinese, Chinese Americans, and immigrant communities more broadly. In early May the New York Times reported that long before the COVID-19 outbreak, Stephen Miller, Trump’s chief immigration advisor, was looking to link various diseases to immigrants as an excuse to seal borders and increase deportations. When students study the historical antecedents to these efforts, they are better equipped to resist white supremacist attempts to equate disease with communities of color now.

In this moment, teachers building online social justice curriculum and parents assisting with distance learning are in a position to teach our children about historical injustices such as those visited upon the Chinese American community at the turn of the 20th century, as well as share historical victories won through resistance and protestations. And we can make connections to this history as we organize to resist Anti-Asian racism during the coronavirus crisis.

Historical Resources

“American Racism in the Time of Plagues,” by Andrew Lanham. Boston Review.

Contagious Divides: Epidemics and Race in San Francisco’s Chinatown, by Nayan Shah. UC Press.

“The ‘Chinese Flu’ Is Part of a Long History of Racializing Disease,” by Carl Abbott. Citylab.

“The Disastrous Cordon Sanitaire Used on Honolulu’s Chinatown in 1900,” by Rebecca Onion. Slate.

“Mike Davis on Coronavirus Politics,” interview by Daniel Denvir. The Dig podcast, March 20, 2020.

Orientalism by Edward Said. Pantheon Books.

“Of Medicine, Race, and American Law: The Bubonic Plague Outbreak of 1900,” by Charles McClain, Law & Social Inquiry, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Summer 1988), pp. 447–513.

Plague and Fire: Battling Black Death and the 1900 Burning of Honolulu’s Chinatown, by James C. Mohr. Oxford University Press.

“Review: American Orientalism,” by Mae M. Ngai. Reviews in American History, Vol. 28, No. 3 (September 2000), pp. 408–415.

“Topics in Chronicling America — Bubonic Plague in Chinatown.” Original historic documents from the Library of Congress.