“I Am a Feather”

“I Am” poems based on “The Delight Song of Tsoai-Talee”

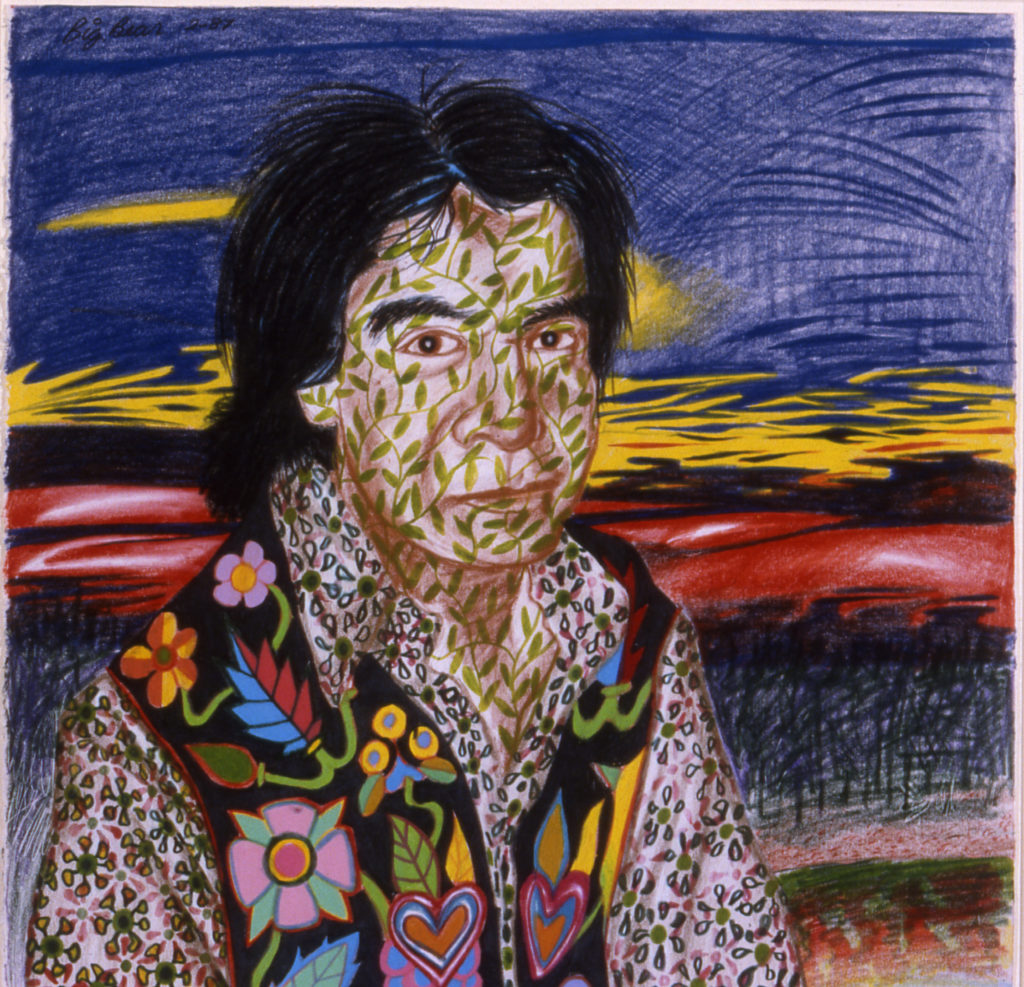

Illustrator: Frank Big Bear

“I liked poetry since 2nd grade when Ms. Stili had us memorize ‘Honey I Love,’ but it wasn’t until 5th grade and this project that I realize I’m a poet too,” wrote Juanita as she reflected on the bilingual poetry book that she made in my 5th-grade classroom.

I weave poetry into my classroom from the first day through our end-of-year ceremony when we tearfully send our students off to middle school.

I can’t imagine an elementary classroom without poetry. It stirs children’s imaginations and encourages wordplay. It brings dull topics alive and provokes thinking and talk about concepts like prejudice, segregation, and friendship. It’s a pathway to writing for my most reluctant students. And it can work wonders in helping students improve their confidence and skills in speaking to an audience.

Poetry has made my three decades of teaching more powerful and joyful.

Over the years, I’ve collected dozens of books of poetry for children, stuffed into crates and bins in my classroom. Students demand to “borrow” them and take them home. Despite my pleading and best attempts at record-keeping, each year my pocketbook takes a hit as I resupply my collection of books. But it’s worth it.

One model that I return to again and again is Kiowa poet and author Scott N. Momaday’s “The Delight Song of Tsoai-talee.” I use the poem for several reasons: its simple yet powerful images, the sense of wonder about nature it engenders, and its format, which lends it to being a useful model. It’s also a beautiful and accessible example of what Momaday calls “Pan-Indian” cultural values.

I introduce Momaday and his poem during our class study of Native Americans by writing the author and title on the board for my students to copy into their Poems We Studied log. I tell the students that Momaday was born in 1934, during the Great Depression. Although he is Kiowa, he lived on Navajo, Apache, and Pueblo reservations in the Southwest when he was a child. His father was a great storyteller and told him many stories from the Kiowa oral tradition. His mother was a writer. Tsoai-talee is his Indian name; it means rock tree boy. In addition to writing beautiful poetry, Momaday is a novelist. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for his novel House Made of Dawn.

I then challenge my students to see if they have enough willpower to close their eyes and listen for about a minute while I read Momaday’s poem (sometimes difficult for 10-year-olds): “As you listen to each line try to imagine it as a photo in your mind.” The poem begins:

I am a feather in the bright sky

I am the blue horse that runs in the plain

I am the fish that rolls, shining, in the water

I am the shadow that follows a child

I am the evening light, the lustre of meadows

After the first reading, I ask students what they remember. I write down a few phrases they call out and then pass out the poem and a yellow highlighter, but insist they keep the cap on. I read the poem again asking them to read along silently.

Then I say: “Now I want you to read it to yourself and highlight your three favorite lines. When you have highlighted the lines, turn to a partner, share the lines you’ve chosen, and tell them why you like those lines.”

After they share, I project a copy of the poem on the board and ask for volunteers to tell us their favorite line and explain why. The responses and reasons vary. Some are memorable:

“I like the ‘angle of geese in the winter sky’ because it’s like geometry.”

“I like ‘the shadow that follows the child’ because when the sun’s out it’s like you can’t get rid of the shadow.”

As each student shares, I ask how many others had it as one of their top three and we note the number next to the line. Then I ask: “OK, based on what you liked and what you see in the poem, if you were going to tell someone how to write an ‘I am’ poem patterned after N. Scott Momaday, what would you say?”

Hands go up. “Each line starts with ‘I am.'” Most hands go down. The remaining volunteers offer a variety of suggestions:

“It’s about nature.”

“It’s about something that connects with you like math or your feet.”

“It’s about an animal doing something.”

“It’s happy like the person is happy to see nature.”

As the students give suggestions I write them on a tag board poster so we have a class record of what we agree are some possible components of an “I Am” poem. “Are you ready to write your own ‘I Am’ poem?” I ask.

“I Am a Strong Apple Tree”

The students are eager to write. But I give some explicit instructions: “I want you to use what we learned from this poem to write one of your own. Think about things in nature that you really like.” I emphasize that I will not accept a simple statement like “I am a tiger.” I say: “Look at Momaday’s poem. Never does he just say he’s something—there is always an interesting description.” Finally, I say it has to have at least 10 lines, but “if you get going, just keep on writing.”

The students then begin to write. I circulate, watching for examples of lines that are rich in language and imagery but aren’t just copies of Momaday’s phrases. I ask students to pause and put their pencils down as I read a student’s line. I continue this to help students who are stuck and to motivate those who need a push to add more detail. Many students will finish during writing workshop. For others, completing the poem is a homework assignment.

During the next writing workshop, I do a class edit with two or three of the students’ drafts of differing quality. I make a copy of the poem to project on the whiteboard and have the student read it out loud. If they’re too shy, I read it myself. I first ask students what they like about the poem. I then ask for questions or suggestions for improvements. Most often the suggestions are to add detail to “paint a picture in our minds” —something I am fond of saying to my student writers.

I then tell the class: “Now it’s your turn to work with a partner and help each other improve your poems. Remember the three steps of peer editing we use in our class: After you read it together, say what you like about the poem, then ask questions, and finally, make some suggestions.”

The students pair up to peer edit and write their second draft. In some cases, I sit with a group of students who have special needs or didn’t turn in their homework or were absent the previous day. I require students to turn in both their first and second drafts so I can see their changes.

The student work is impressive. Juan writes: “I am the strong apple tree in my backyard standing up to storms.”

Hattie writes: “I am the sun in the sky burning the people below.”

Francisco writes: “I am an Arctic wolf camouflaged in the snow waiting for victory.”

Veronica writes: “I am the person that you love and care for.”

José writes:

I Am

By José

I am a baby tiger wrestling with my brother.

I am a bald eagle soaring in the sky looking for my prey.

I am a sunflower resting on the ground after the squirrel ate my seeds.

I am the sandy beach where the ocean waves are breaking the castles that the kids built.

I am the moon shining in the dark providing light for those who are lost.

I am a little toy truck whose owner plays with me and smiles.

Based on True Life

One year, several months after the class had written their “I Am” poems, I was teaching double-digit multiplication and division problem-solving through a “sweatshop math project.” While I was showing photos of child laborers, Osvaldo raised his hand and said: “I know all about that. I used to do that when I was 5 years old.”

“You did what?” I asked.

“I worked in the fields with mi abuela—my grandmother.”

I thanked him for his comment and we talked some more. I asked him if he liked working in the fields—secretly hoping he’d confirm the problems with child labor that we’d been learning about.

“Yeah, it was sort of fun for a while.”

“Didn’t you want to go to school instead?”

“No,” he said, full well knowing I was hoping for a different answer. “The teachers are mean there. If you misbehaved in that school, the teacher put biting ants down your back.”

Stunned, my only response was, “Oh, that’s reason enough not to go to school.”

Later that day, during writing time, I asked Osvaldo to write a poem about this experience. Eventually he came up to me with this poem:

A 5-Year-Old Boy

based on the true life of OsvaldoI am a 5-year-old boy working to support my family

I am a boy walking for a mile just to get clean water out of the pozo

I am a boy carrying a sack full of caña more than a mile

I am a boy watching for snakes and scorpions while working

I am a boy carrying food for my farm animals

I am a boy working for hours in the sun

I am a boy working in pain in my back and arms and legs

I am a boy sleeping with pain and bruises on my fingers

I told him how much I liked it and how his words painted a picture for me. I asked if he’d be willing to read it to everyone. As we finished writing workshop, I asked Osvaldo to come to the front. His classmates sat glued to his every word. Their applause sparked a wide grin from Osvaldo. The following morning he brought in another poem, handing it to me with a big smile on his face.

I am a 5-year-old boy living in the United States

I am a boy eating strange food

I am a boy going to school

I am a boy seeing for my first time a show

I am a boy having my first game station

I am a boy seeing other people like African Americans and Puerto Ricans

I am a boy living happily in my new home

I am a boy feeling sad for being far away from my grandma and grandpa

Osvaldo’s status in the class rose over those few days. Although he had been spending most of his time with other Spanish-dominant students, soon a more diverse group of students clustered around him. Although Osvaldo’s poems didn’t fit the metaphorical model I suggested, poetry provided an important way for him to express his thoughts and feelings, and to share them with the class. Osvaldo connected to the math project in a personal way and it seemed to increase the whole class’s interest in the entire project. And it was all tied to the power of poetry.

This article appears in our book, Rhythm and Resistance: Teaching Poetry for Social Justice.