Preview of Article:

Hunger, Academic Success, and the Hard Bigotry of Indifference

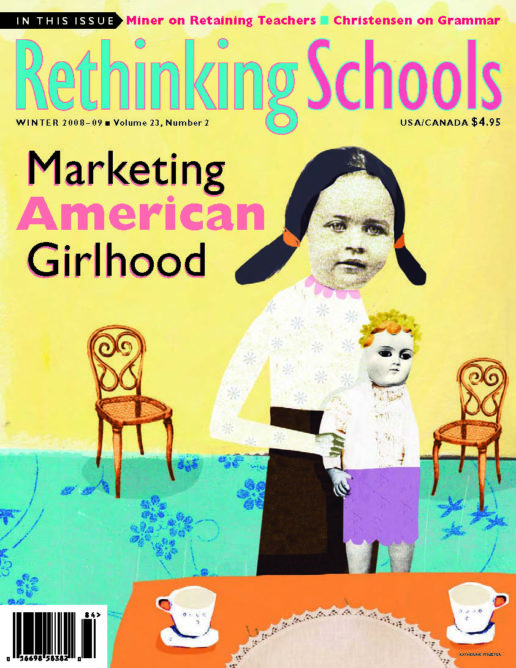

Illustrator: JD King

If you think poverty can damage academic achievement, you obviously haven’t been paying attention these last eight years. Had you talked with George W. Bush and suggested that poverty and academic achievement are connected, he’d surely have insisted you’re partaking in the “soft bigotry of low expectations.” You’re making “excuses” for poor children’s academic problems compared with the greater academic success of children from affluent homes. Regardless of their social conditions, “all children can learn,” Bush repeated in speech after speech on education. Forget poverty! All that is needed for educational excellence is direct instruction, “scientifically-based” prepackaged materials, lots of testing, school choice, and punishment of “failing schools.” This remarkable brew will transcend the effects of poverty, or so it was believed by the president, whose strong faith in the singular power of this brew allowed him to feel comfortable repeatedly reducing every area of the federal budget essential to poor children’s fundamental well-being.

Aiding Bush in this “no excuses” campaign have been educators and psychologists whose work has focused narrowly on instruction, cognition, and brain activity, without a word about social class conditions impacting children for better or worse. An example is Sally Shaywitz, a pediatrician and reading researcher at Yale University, an author of National Reading Panel Report (the theoretical underpinning of Bush’s Reading First policy), and a steering committee member of the 2004 National Educators for Bush. A major booster of the lockstep, skills-heavy pathway to literacy, Shaywitz has confidently asserted that “at last we know the specific steps a child or adult must take to build and then reinforce the neural pathways deep within the brain for skilled reading.” Offering “a new and complete science-based program for reading problems at any level” and self-described as a “working scientist who has wrestled with the conundrum” of reading problems “for more than two decades,” Shaywitz, like similar promoters of Bush’s educational policies, has never seen poor children’s socio-economic conditions as part of the “conundrum” with which to grapple.

Nonetheless, despite their relentless appeals to “science” in adjudicating educational matters, the Bush educational scientists have clearly disregarded a lot of science that shows how social class conditions directly influence academic outcomes. Certainly many poor children manage to succeed academically, but they do so while facing onerous forces that, but for the cruelty of policy makers in this rich nation, they should never have to confront in the first place. A graphic example of the effect of these social class conditions and the cruelty that generates them is hunger.