How My 4th-Grade Class Passed a Law on Teaching Mexican “Repatriation”

My 4th graders listened in silence as 89-year-old Emilia Castaneda told us her story. Born a U.S. citizen of Mexican heritage, she was just starting 4th grade in East Los Angeles in 1935. She came home from school one day to find her father, a legal resident and homeowner, packing their belongings. He was a master contractor, but could not find work. Instead, he was greeted everywhere by signs that said “No Mexicans Need Apply.”

The Hoover administration explained that the jobs were for “real Americans,” meaning white Americans. Emilia and her family were forced to get on a train to Mexico. Supposedly, the government sold their family’s house and used that money for their transportation.

“In Mexico,” Emilia explained to a sea of somber faces, “we lived under a tree and in a tent for a while. We had no running water and we had to hang our food on ropes so the rats couldn’t get it.” She quit school because she didn’t speak Spanish and was bullied. At 10 years old, Emilia found a job babysitting and carrying water to homes. “I was not allowed to return to the United States until I was 18,” Emilia told us.

My students were horrified, especially when they learned that the 1.2 million U.S. citizens of Mexican descent who had been unconstitutionally deported in the 1930s as part of the so-called “Mexican Repatriation” never received a federal apology for their treatment.

As a class, we looked in our Harcourt history textbooks and found only one sentence on the Bracero Program — the only reference to Mexican immigration in California in the whole textbook — and nothing about U.S. citizens like Emilia who lost everything when they were unlawfully removed from their homes and forced to “return” to a country some of them had never set foot in.

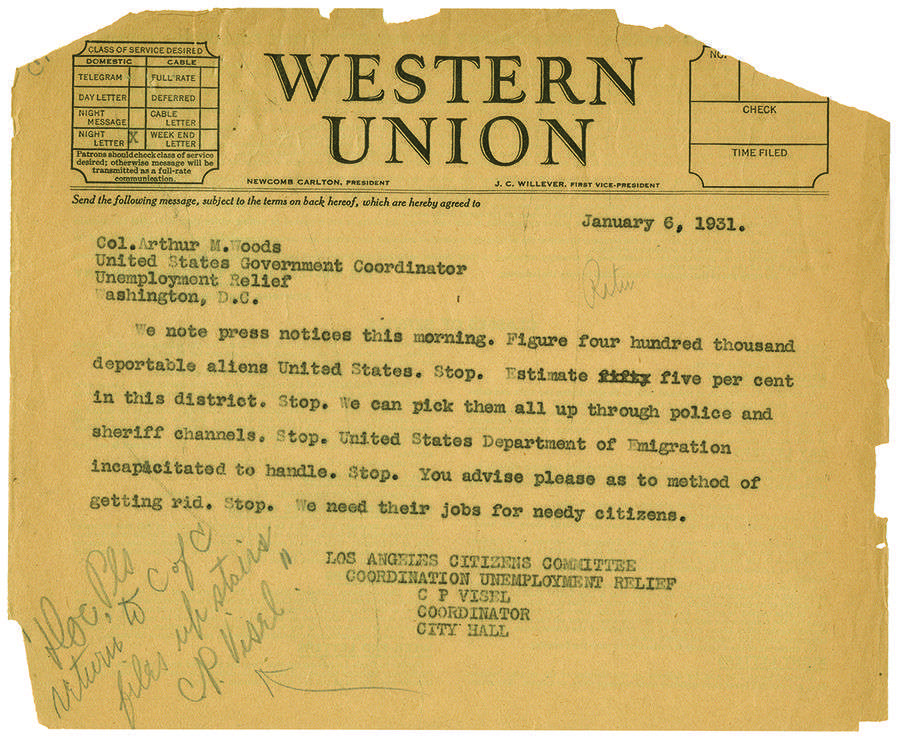

The great majority of students in my class came from first-generation immigrant families. For them, this omission was a personal affront. Ana Ramos, our student teacher from California State University at Dominguez Hills, framed our unit on immigration around the unconstitutional deportations of the 1930s — a chapter of our history previously unknown to me. We started with photos depicting the deportations that we found through a Google search: the train station, cars packed high with belongings on the side of the road, a government letter of deportation, the “We Serve Whites Only — No Spanish or Mexicans” signs that could be found on businesses, and photos of the camp-like conditions that awaited those who returned to Mexico. We created an inquiry chart for each photo, and students went around the room with a partner and listed observations on one side and questions on the other. We also viewed oral interviews of other survivors on YouTube, where they are available as part of a video made by California State Senator Joseph Dunn, author of the “Apology Act for the 1930s Mexican Repatriation Program” that passed in 2006 and resulted in an official apology from the state of California. Our class discussion after these interviews focused on the essential question: Why would a government deport its own citizens? We also read letters and interviews that we excerpted from the book Decade of Betrayal by Francisco Balderrama and Raymond Rodrguez.

As a point of comparison, we studied the Chinese Exclusion Act, mostly through analyzing and discussing political cartoons, and we read about the 2012 federal apology for that legislation. Our students were perplexed and angered: Why would the federal government apologize for the Chinese Exclusion Act, but not the Mexican Repatriation? This learning struck a chord with the students. The deportations that have shaken their own community in recent years were on their minds as they learned about what happened in the past.

As a culmination to the unit, the students wrote letters to then-President Obama asking for a federal apology. Joaquin wrote, “We know what’s right and we know what’s wrong. Right now we need to change a wrong thing into a right thing. We need to say sorry to the people who were born here.”

Before we received a response from our president, Ms. Ramos had to leave us to move on to her next student-teaching assignment. I was satisfied when Obama wrote us back, encouraging the students to continue fighting for a more just world, and I thought this was a good conclusion to our unit. The students, on the other hand, were horrified. I read the form letter aloud and there was a silence, broken only by 10-year-old Jos: “He didn’t even mention the deportations or an apology!” Isabel suggested, “Maybe President Obama never learned about deportations in school because it was not in his history textbook either.”

I had to follow their lead and realize that this was not the end of our unit. We held a class meeting and, during our brainstorm, Erick said he wanted to go to Sacramento or Washington, D.C., so that the politicians would listen to us. We added the idea to our list, but I secretly smiled at his improbable aspiration; I would think back to that moment and my own doubt as we walked the halls of the Capitol building in Sacramento less than a year later.

The students got into groups to create projects that would teach others about the Mexican “Repatriation.” One group stated in their oral letter, “The great- granddaughters and the great-grandsons need an apology, Mr. President.” In another group’s poem, they captured the tragedy of the repatriations: “Once in the 1930s, people lost their homes, their education, their jobs.”

I looped up to 5th grade with my students, and that school year I invited our representative to the California State Assembly, Assemblymember Cristina Garcia, to talk to the students about immigration today. The students taught her what they knew about the unconstitutional deportations of the 1930s and performed their projects for her, and before she left, she recommended we enter her contest called “There Ought to Be a Law.” She let the students know that as a member of the California Assembly, she had no control over a federal apology, but that we could try to make a law requiring that this subject be included in California history textbooks.

We won the contest, and thanks to our district’s support and that of Assemblymember Garcia’s office, all 34 5th graders and parent volunteers were off on a bus to Sacramento to speak to the Assembly Education Committee in support of AB 146, for the inclusion of the “Mexican Repatriation” in California history textbooks. The students commanded attention as they walked down the halls of their state Capitol; it really looked like and felt like they belonged there. Five students gave speeches and 29 others got to voice their support for AB 146. Makayla confidently stated, “In our search, we were unable to find any information about the subject in our history textbooks.” Janet added, “This era should be as important as many other movements marked in our textbooks today. Isn’t the Mexican Repatriation as important as the Chinese Exclusion Act, as the Japanese Internment, as the Bracero Program, and as the Indian Removal Act? We know it is just as important.”

We learned that it takes seven steps for a bill to become a law in California, but we didn’t count on how many times AB 146 would be postponed, amended, and returned to committee. Finally, when my students were in 6th grade at the middle school, Gov. Jerry Brown signed AB 146 into law. The majority of my former students rushed to my class after school to celebrate. I loved what I heard: “Now every student in California can learn about the unconstitutional deportations of the 1930s!” “Now maybe the survivors will get an apology.” Every comment was about the cause and not about their victory. I was humbled.

Last year I had 4th graders who learned about the “Mexican Repatriation” from the original class. What they created was a robust unit that included a new chapter for the history book and skits and presentations that were the main fuel for their activism. The new class felt it was their job to continue asking for a federal apology. They researched our representative in the Congress, Congresswoman Lucille Roybal-Allard, and decided she would be the perfect person to help us get a federal apology. After writing letters to our congresswoman, she responded that she has worked on an apology in the past, and was interested in pursuing it again. Since then the congresswoman has introduced two bills, HR 6314 (2016) and HR 1412 (2017), recommending a committee be formed to officially study what happened during the Mexican Repatriation. Her visit to our class was another powerful example of our elected officials listening to the voice of children.

It’s wonderful to feel that our students have made a difference, but making change cannot be the only goal for our teaching. It is the process of making the change that empowers students to know they cannot be bystanders in their lives. The act of writing a persuasive letter, of verbally defending an idea to their government representatives, of public speaking with confidence and conviction, of persevering when confronted with negativity: This process changes lives. Even though young students are learning about some really awful history, they are doing something about it. And that gives them hope.

The students wanted to share the lesson with the entire school, and as one of them, Jennifer, told a group of 3rd graders: “So our work is not done. Join us in working for justice.”

Leslie Hiatt teaches 5th grade in Bell Gardens, California. Ana Ramos teaches kindergarten in Los Angeles.