Honoring Exonerees

Poetry and Art as a Background Activity for a DNA Electrophoresis Lab

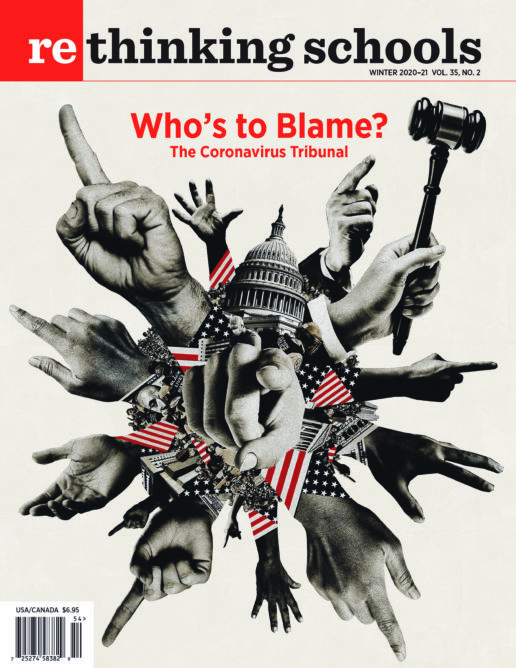

Illustrator: Adriá Fruitós

“What do you think of when you hear ‘DNA testing?’” I ask.

“Cops use DNA to solve crimes,” says Gloria. “I’ve seen it on Homicide.”

“They can use DNA from blood and hair and other stuff,” Nate says. “It’s in the nucleus of cells.”

This warm-up conversation on the first day of a DNA testing unit I teach often centers on DNA being used to prove guilt. Sometimes students bring up rape kits or paternity testing, and in the last couple of years, students have often brought up personalized genetics tests for health and ancestry. But I have yet to hear students mention that DNA testing can be used to help prove someone’s innocence and exonerate them after a conviction. DNA testing has revolutionized how people are convicted, but it has also been underutilized and misunderstood by prosecutors, judges, and juries. Sometimes even DNA evidence hasn’t been enough to keep innocent people out of jail.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world. The Prison Policy Initiative puts the current U.S. prison population at 2.3 million, 20 percent of whom are awaiting trial. In a Chicago Tribune op-ed, John Grisham, best-selling author and member of the board of directors of the Innocence Project, wrote that an estimated 2 to 10 percent of convictions are false. Our media largely ignores the innocent in prison, leaving students unaware of these injustices. According to the Innocence Project’s website, since 1989 there have been only 367 exonerations based on DNA testing; 61 percent of these cases have been of African Americans. DNA testing has presumably helped lower the number of wrongfully convicted people in the criminal justice system, yet there are many instances of delayed testing, race bias, and juries and judges not fully understanding the science and how unique one’s own DNA sequence is.

Science is often taught in ways that falsely silo content objectives and context, particularly when that context includes social justice or difficult conversations. I developed this “Honoring Exonerees” lesson as a way to connect students to how science can support justice — so students can see how DNA can be used to right injustices of misidentification and overturn false convictions.

I am often surprised by some of my students’ deeply held belief that the justice system works equally for all people and the subsequent belief that all people convicted were done so in a fair and equal manner. Even with DNA evidence, there are still people who have been falsely convicted of serious crimes in prison and others for whom evidence was destroyed or never properly collected. Because of the instances where racism played a major role in false convictions, I also want my students to use this lesson to examine what we mean by “guilt” and “innocence” and how we view those who are “guilty.” People are convicted of some crimes simply because they are poor and cannot afford good defense attorneys. And some actions are “crimes” because of racist laws. For example, segregation laws allowed the police to arrest Black people for entering “whites only” spaces. Today, a disproportionate number of Black people and people of color are in prison for drug offenses that are no longer illegal. So although I sometimes use the term “guilt” and “innocence” as I talk with students, I try to talk about convictions and wrongful or false convictions instead.

I am often surprised by some of my students’ deeply held belief that the justice system works equally for all people and the subsequent belief that all people convicted were done so in a fair and equal manner.

As a science teacher, I often focus on what future scientists will need to know or what science young people need to know in order to make informed decisions. But I also must teach as if I am teaching future lawyers, future politicians, and certainly future voters and members of juries. It is critical to understand the prejudices inherent in our criminal justice system. My students also need to understand how the criminal justice system interfaces with scientific tools, that the racism perpetuated through the misuse and misunderstanding of these tools needs to change, and that this change will only come through an understanding of both.

I teach biology and biotechnology in a small community in northwest Washington. Our school is approximately half white students and 40 percent Latinx. When I developed this lesson, I taught the same classes in a predominantly Black school in Portland, Oregon. I have taught this lesson in biotechnology classes but it could also be used in biology classes during genetics units or in other courses that discuss the criminal justice system. I have found that regardless of the racial makeup of the class, this lesson speaks to students’ strong sense of justice. I have also found that this lesson brings in students who may be intimidated by writing research papers or those who have more confidence in their abilities to write song lyrics and poetry. Because poetry and art are typically far more expressive than a typical research paper, students express their ideas surrounding justice for the wrongfully convicted more clearly and fully. Students demonstrate empathy, sadness, and anger — the emotions I’ve seen come up the most in this lesson — in ways that would be difficult in a typical science lab write-up.

***

After our initial discussion about what students think of when they hear the phrase “DNA testing,” we watch the documentary After Innocence. This film covers multiple stories of people who have been exonerated through the work of the Innocence Project, a group of lawyers that fights for people who have been convicted despite strong evidence of innocence.

While we watch the film, I have students take notes on a sheet that has only the exonerees’ names and locations. “Focus on their stories. How long were they in prison? What was it like when they got out? Did they receive compensation? How was DNA used to prove their innocence?” This format produces notes that are mini-biographies of the exonerees, the details of which are used in the poetry and art made at the end of the lesson. By not writing specific questions or the common fill-in-the-blank style of movie notes, students are able to center what is most meaningful to them rather than focusing on very specific facts.

There are a couple times I pause the film for brief discussions on things like how often eyewitnesses’ mistaken identity occurs in these cases. In the case of Wilton Dedge, a white man from Florida who spent more than 20 years in prison, for example, the actual rapist was significantly taller than him. We also see Dedge’s lawyers argue for a second set of DNA evidence to be tested because the first set of DNA, which excluded Dedge from being the perpetrator, wasn’t enough to exonerate him. I ask: “Why do you think a prosecutor would charge someone who doesn’t match the victim’s description? What could make someone’s image of a perpetrator change in their mind?”

Common responses include “The victim just wants it to be over” or “The prosecutor might have pressure to find the perpetrator.” I also make sure that students understand that rape cases have other issues that do not favor the victim, such as the backlog of rape kits to be tested, and that this backlog and prosecutors ignoring DNA evidence are in fact related injustices as both are a result of the underutilization and misuse of scientific tools.

Once we are done with the film, I ask “What do you hope to accomplish between the ages of 20 and 40? What are your dreams for the 20 years after you graduate high school?” This is roughly the age range that several of the exonerees spent locked up, so this question is designed to bring home the gravity of losing those years to being in prison.

“That is when you build your career, and have kids, and find a partner,” Erick says. “I want all that.”

“I am going to go to college. These guys didn’t get to go to college,” Sophia adds.

We also talk about how the world continued to change while the men were in prison: cell phones, email, and other innovations occurred while most of the profiled exonerees were in prison (the film was released in 2005). There is a scene in the film where one of the men goes back to his childhood house and into his old bedroom directly after being released from prison. “He has to live with his parents, it’s like he’s still 20, but really he’s just lost 20 years. It’s really sad,” Alexis comments.

Some of the men in the film who have been out for a while discuss the hardships they face, particularly because many of their records were not actually cleared. The justice system in many states does not yet have a method to correct conviction mistakes, nor are the men typically compensated for their time. Vincent Moto, who served nine years, and his family discuss how, after that much time gone, people in their neighborhood just assume he was out on parole for a rape that was remembered in the community, not that he was out because he is innocent. Calvin Willis (21 years served) is shown trying to explain his unique situation at a church and on the radio, hoping the business community in his area will help him figure out how to open a barbershop. And the film shows Herman Atkins (12 years served) receiving a diploma, and we hear about him working on a deferred dream of getting a doctorate.

Moto, Willis, and Atkins are Black, and their stories also demonstrate race-based issues with eyewitness identification. All three had eyewitness misidentification as a contributing cause of conviction. Sixty-one percent of DNA exonerations are of Black people, and in the film four of the eight men profiled are Black. Students notice the number of Black exonerees in the film. “Are Black people more likely to be falsely convicted?” Briah asks.

“People have been shown to have a harder time correctly identifying people of different races,” I respond.

“Is this why white teachers have a harder time learning our names?” Ray, a Black student, asks.

“It could be,” I answer. The first time this came up in class, I did a dangerous teacher move: a live Google search. Although I don’t remember exactly what came up, it was something similar to this quote from the abstract of Bryan Scott Ryan’s article “Alleviating Own-Race Bias in Cross-Racial Identifications”:

One prominent factor that makes eyewitness testimony faulty is own-race bias; individuals are generally better at recognizing members of their own race and tend to be highly inaccurate in identifying persons of other races. This instance, where a witness of one race attempts to identify a member of another race, is referred to as a cross-racial identification. Own-race bias in cross-racial identifications creates racial discrimination in the American judicial system, where a majority of defendants in criminal cases are minorities. Courts have traditionally ignored the problem of own-race bias in the courtroom, believing that traditional safeguards such as cross-examination and summation effectively resolve racial discrimination in the judicial system.

This is illustrated in another powerful story in the film. Ronald Cotton, a Black man, was falsely convicted of raping Jennifer Thompson-Cannino, a white woman, and served 10 years before DNA evidence was used to exonerate him. Thompson-Cannino had falsely identified him as the assailant. In a pretty amazing turn, Cotton and Thompson-Cannino are now activists and work together to speak out against using eyewitness identification. They call themselves “friends” in the film. Cotton demonstrates an incredible amount of empathy for her as a violent crime victim. Thompson-Cannino demonstrates remorse and regret that her false identification caused Cotton such incredible harm.

***

When I first developed this lesson, my students, in their English classes taught by Rethinking Schools editor Linda Christensen, were writing odes inspired by Myrlin Hepworth’s beautiful tribute to Ritchie Valens titled “Two String Guitar.” So my students were familiar with this method of honoring someone. Hepworth weaves details from Valens’ life with injustices he faced; in the poem, Hepworth talks directly to Valens:

Richard Valenzuela,

they called you Ritchie.

Said Valenzuela

was too much for a gringo’s tongue.

Said it would taste bad in their mouths

if they said it,

so they cut your name in half to Valens,

and you swallowed that taste down,

stood tall like a Pachuco

and signed that contract

para su familia para su música

Ritchie Valens

It was always about your music.You felt it tumble inside your chest as a boy,

playing a guitar with only two strings.

And when your neighbor caught you,

you thought he would be angry over your racket,

instead he helped you repair the instrument,

and taught you how to grip it correctly.

Hepworth’s mentor text helps my students see how to take the details from the exonerees’ lives to honor their stories. Christensen wrote about her lesson, “Singing Up Our Ancestors,” in the Summer 2014 issue of Rethinking Schools. This article should be read before recreating this method of using poems in science classes.

In subsequent years with students who had not done the same work in their English classes, we read both Hepworth’s poem and one I wrote about Wilton Dedge as models. I ask: “What lines tell you the most about Valens? Where does Hepworth provide details about Valens’ life?” Then we read the poem as writers instead of readers. We “raise the bones” as Christensen describes in her article: “What are Hepworth’s poetic landmarks? What do you notice about how he moves the poem forward? What are his hooks?”

Then I ask a question about the film to help students brainstorm specifics: “What details stood out to you in the movie that give you clues about the exonerees’ lives and personalities?”

“Vincent Moto helps his whole family with laundry, maybe so they visit more,” says Jaylen.

“Nick Yarris drives a Jeep so he is inside less,” shouts out Will.

This discussion about personal details as well as the conversation about Hepworth’s writing — the beat of the poem, the imagery, the metaphors — are not our typical science class conversations, but doing so gives us a method to see the exonerees as real people whose lives were stolen. We also talk about how to incorporate DNA testing vocabulary into our poems. Some years we list words out on the whiteboard, and some years we refer to review work we’ve done in our notebook.

The poems the students write take on their own lives and I learn about my students when they perform them. I hear their styles and their pleas for justice in new ways. Students rap, slam, sing their words. Kids who don’t speak in class rise up to share their writing. I am never disappointed by the passion students put into their odes.

Sinnamon wrote about Calvin Willis, who was in prison for 21 years and whose case highlights issues with eyewitness identifications:

Ode to Calvin Willis

By Sinnamon Thomas

They chose you out of a lineup of 7 men

Heads up 7 up, 6 men innocent

You looked exact to another individual

Formulated as guilty

Filthy

Never tested the residual

Slap on your wrist

Told you would never taste the crisp

Or the fresh air

Just look at the bland cell wall

You could stare

7 years go by

And you’re the wrong guy

Your freedom denied

And you’re just not the guy

Your babies mature, almost grown

Doing the best hurts, for it’s a simple call home

Then after 21 years of your time given

They say go free and a different life you’ll be livin’

Their mistakes were livid

And the fact remains

The genetic sperm from that appointed rape

Did not match your name.

In a Tanka-style poem about Calvin Willis, Dayton admired Willis for creating a new life after being imprisoned:

Calvin Willis, Tanka Poem (57577)

By Dayton Cadman

Innocent trashman

Mistaken for the cowboy

DNA, trashcan

Discovered as type O boy

No questions asked, convicted

Death row, 20 years

DNA contradiction

Liberty and tears

Seeking his own redemption

God knows the statesmen wouldn’t

Time you can’t repair

But sulking won’t help either

So he just cuts hair

Lives life not in spite, rather

In light of his misfortune

Dayton also brings in information about blood typing that originally did not exclude Willis from being a potential perpetrator (although hair analysis did exclude him before the conviction). DNA testing confirmed his innocence post-conviction. There were other issues with evidence: Willis was size 29 waist and boxers left at the scene were size 40.

An excerpt from Vincent Singer’s poem, an ode to all the exonerees, shows how he creatively demonstrated a deep understanding of the purpose of DNA in the body:

A transcript of the A, T, C, Gs

Translating into the maps that are eyes

Nose, ears, and mouths

The map that breeds the smiles that we see

The laughter that we listen to

This bio-archive of the human component

Can be the savior of the men who are shun from the sun

Vincent uses terms that describe how protein synthesis works: transcription is the reading of DNA to RNA, translation is when mRNA is used as instructions to build a protein. A, T, C, and Gs refer to the nucleotides that make up DNA.

This tribute has evolved over the years of teaching about exonerees to include art pieces and portraits. I also give students the option to write a letter to a congressperson to demand that states change the way they treat exonerees. Most students who opt to write a letter ask that states expunge exoneree records and award financial compensation for the years lost. One year (in Portland) I invited two lawyers from the Oregon chapter of the Innocence Project to speak to the class. Students were able to see how these lawyers needed to understand the science we learn about in class, and through writing letters to members of Congress, they can also explain why it is so important that our government leaders understand scientific tools.

We have class time to absorb all of the work and reflect on what the justice system has done to the exonerees. Most students read their poems aloud and we do a gallery walk of art pieces. When students read aloud, we give three positive comments; we do the same on large pieces of paper next to art pieces.

Although this lesson, including the film, typically takes only about two 90-minute class sessions, the emotional connection students gain to the plight of the exonerees is deep. Through this emotional connection, students see how prosecutors secure convictions from juries by relying solely on outdated and flawed tools such as eyewitness identifications and hair “matches” — and how legal activists and proactive justice departments can use technological advances in DNA testing to correct injustices.

After this reflection we start our lab. The “Honoring Exonerees” lesson gives meaning to why we need to know about things like tandem repeats and point mutations in DNA sequences. I sometimes give a short lecture reviewing DNA structure and mutation types before launching into the lab, and sometimes I can see from the way the students incorporate vocabulary terms into the poetry that this is not necessary. We spend some time at this point discussing the charge of DNA, how we measure length of DNA fragments, how restriction enzymes work, and how to read a DNA ladder.

I typically use a kit from Carolina Biological Supply but have also used electrophoresis supplies from local universities. Although we follow the lab protocols provided, I also usually do some pre-lab work with teaching how to use pipettes to fill the wells of the gels and we practice with a dye lab that looks at how the charges and molecular sizes of dye molecules affects how they move through an agarose gel.

I also change the context of the lab as most of these kits have a little story about catching someone stealing cookies or some other innocuous story line. Although I keep the crime low-level, I add to the story to include mistaken identity or false accusations. In this way, we keep the focus on using the science, not unproven methods, to identify the perpetrator. I understand the intention is to not make crime the focus, but stories about stealing cookies undermine the true power of DNA testing. The canned lab stories stand in stark contrast to the profound stories of exonerees. To not continue with the gravity of consequences of DNA testing feels disrespectful to the people who have spent decades in prison erroneously.

Using poetry and art projects as a prelab may not seem “rigorous,” but the opposite is true. Students demonstrate the power of DNA testing through empathizing with exonerated people, utilize vocabulary in meaningful ways, and critically analyze how our criminal justice systems interface with scientific methods and data. The future scientists, lawyers, authors, jurors, voters, activists, and witnesses sitting in my classroom need to understand how we can fight systemic racism using both activism and advances in scientific methods.

Science and social justice issues are not mutually exclusive but rather are intertwined in many important ways. That false convictions still occur even when DNA evidence is available, and that these false convictions and subsequent exonerations are so much more likely to happen to Black men, are problems that we need to keep trying to solve. Our students need to both see the problems inherent in our criminal justice systems and see prisoners as individual humans. They need to understand that scientific methods can be used to fight systemic racism and overturn — and hopefully prevent — false convictions.

Support independent, progressive media and subscribe to Rethinking Schools at www.rethinkingschools.org/subscribe