Happening Yesterday, Happened Tomorrow

Teaching the ongoing murders of black men

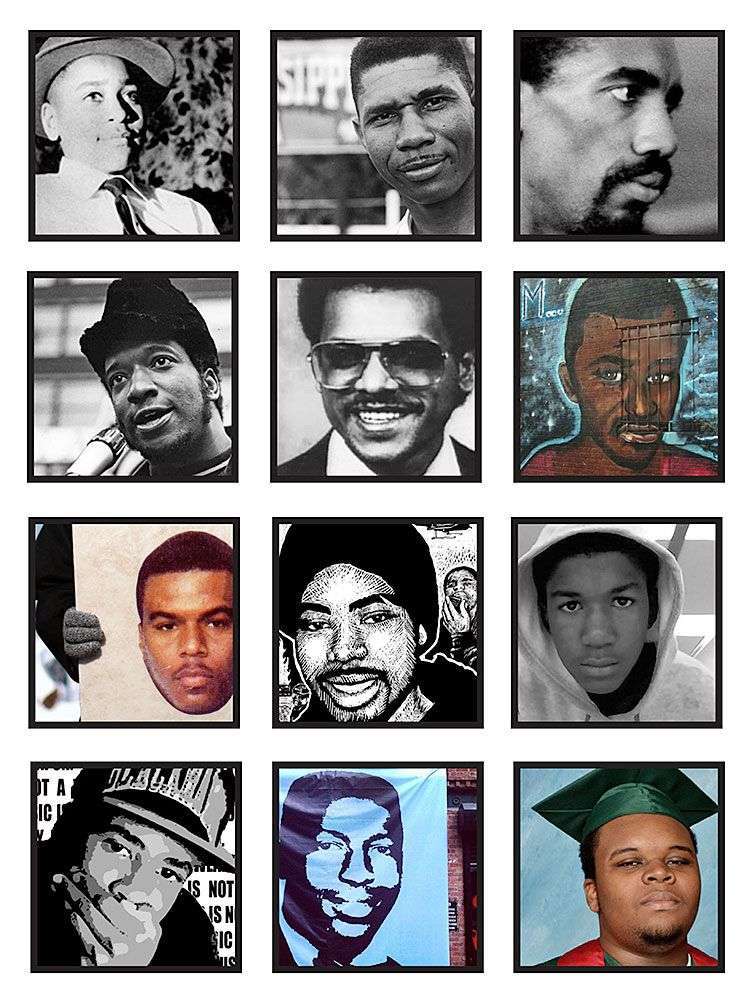

Emmett Till.

Medgar Evers.

Henry Dumas.

Fred Hampton.

Mulugeta Seraw.

Amadou Diallo.

Sean Bell.

Oscar Grant.

Trayvon Martin.

Jordan Davis.

Eric Garner.

Michael Brown.

There is a history in our country of white men killing unarmed black boys and men with little to no consequence. I taught the murders of Sean Bell and Amadou Diallo, using Willie Perdomo’s “Forty-One Bullets Off-Broadway” as the model poem, to a class of 7th graders (“From Pain to Poetry,” fall 2008). But then there was Trayvon Martin, then Jordan Davis, then Michael Brown, and the list keeps growing.

After the murder of Trayvon Martin, I taught a version of “From Pain to Poetry.” I wanted to use Perdomo’s poem again—it is a strong example of how writers use facts and their imaginations to tell a story. I wanted to add a research component because my students needed to develop researching and note-taking skills and, just as important, I needed to show students that racial profiling and police brutality are not new.

Aracelis Girmay’s poem “Night, for Henry Dumas” is a perfect pairing with “Forty-One Bullets Off-Broadway.” We get the intense immersion into one man’s story in Perdomo’s poem, while Girmay plays with time and place, making us acknowledge that the list of black men who have been unjustly killed is long and painful and ongoing. I wanted students to see both as approaches in their own work.

One of my objectives was to have students explore ways that poets use their work to respond to injustice. I also wanted them to create a collaborative performance by the end of the unit, so scaffolding in opportunities to work together was something I needed to think about. I decided to ask students to work in small groups for the entire unit and focus on a person who was killed as a result of racial profiling or police brutality.

“They Were Murdered”

When they came to class on the first day of the unit, there was a plastic bag with jigsaw puzzle pieces in the center of each table. Each group’s puzzle, when put together, was a photo of one of five of the slain men: Henry Dumas, Oscar Grant, Amadou Diallo, Sean Bell, or Trayvon Martin. I made the puzzles by printing the photos on cardstock, turning them over to the blank side, drawing jigsaw pieces, and cutting them out. The pieces were big and easy to assemble, about 10-15 pieces for each photo.

The goal was to get the students to collaborate on creating something. “You have five minutes to work as a group to put the puzzle together,” I told them as they began to pour the pieces out. I walked around the classroom, checking to make sure everyone in the groups was actively participating.

When each group finished, they received an index card with the name of their person written on it. I called out to the class, “Who has Henry Dumas?” The members of that group raised their hands. I taped his photo on the board and wrote his name underneath so that the whole class could see Dumas. I continued this, making a chart on the board with five columns. The last person we added to the board was Trayvon Martin.

I asked the class: “Do you recognize anyone on the board?”

All of the students knew who Trayvon Martin was.

There were a few students who felt they had seen Oscar Grant before. “There’s a movie about him, right?” one student asked. Fruitvale Station, a movie that reconstructs the last 24 hours of Grant’s life, had been released the same weekend as the Zimmerman verdict. (George Zimmerman, who killed Martin, was found not guilty by a jury in Sanford, Florida.)

I asked someone to give a very brief account of what they knew about Martin.

“He was shot by a neighborhood watch guy,” a student answered.

“He was shot because he was wearing a hoodie,” another student shouted.

I asked the class to hold off on adding more. “Based on what you know about Trayvon and Oscar, why do you think these other men are on the board?”

“Because they got shot, too?” James suggested.

“Yes. They were all murdered,” I told the class. “Looking at these photos, what do you notice? What do they have in common?”

Lakeesha noticed that they were all black.

“And they’re all men,” Sami added.

“And they probably didn’t deserve to die,” James blurted out.

I asked him, “What makes you say that?”

He considered what he knew about Martin and Grant. “They didn’t even have weapons on them when they got shot. The others probably didn’t, either.”

“You all are being great critical thinkers. Let’s find out more about these men—what happened to them, how their stories are similar, and where there are differences.” I passed out an article to each of the five groups about the person whose photo they had. “Your group should take turns reading the article out loud. Underline important facts that stand out. If there are strong images in the article, underline those, too.” I ask students to mark up their papers, whether it’s an article or a poem. I think it’s important for them to engage with their handouts, to write questions in the margins, to highlight phrases that grab them. “When you are finished reading the article, let me know.”

Forty-One Bullets Off-Broadway

By Willie Perdomo

It’s not like you were looking at a

vase filled with plastic white roses

while pissing in your mother’s bathroom

and hoped that today was not the day

you bumped into four cops who

happened to wake up with a bad

case of contagious shooting

From the Bronx to El Barrio

we heard you fall face first into

the lobby of your equal opportunity

forty-one bullets like silver push pins

holding up a connect-the-dots picture of Africa

forty-one bullets not giving you enough time

to hit the floor with dignity and

justice for all forty-one bullet shells

trickling onto a bubble gum-stained mosaic

where your body is mapped out

Before your mother kissed you goodbye

she forgot to tell you that American kids

get massacred in gym class

and shot during Sunday sermon

They are mourned for a whole year while

people like you go away quietly

Before you could show your

I.D. and say, “Officer —”

Four regulation Glock clips went achoo

and smoked you into spirit and by the

time a special street unit decided what was

enough another dream submitted an

application for deferral

It was la vida te da sorpresas/sorpresas

te da la vida/ay dios and you probably thought

I was singing from living la vida loca

but be you prince/be you pauper

the skin on your drum makes you

the usual suspect around here

By the time you hit the floor

protest poets came to your rescue

legal eagles got on their cell phones

and booked red eyes to New York

File folders were filled with dream team

pitches for your mother who was on TV

looking suspicious at your defense

knowing that Justice has been known

to keep one eye open for the right price

By the time you hit the floor

the special unit forgot everything they

learned at the academy

The mayor told them to take a few

days off and when they came back he

sent them to go beat up a million young

black men while your blood seeped through

the tile in the lobby of your equal

opportunity from the Bronx to El Barrio

there were enough shots to go around

From Smoking Lovely by Willie Perdomo. Copyright © 2003. Used by permission of author.

Students were eager to learn what happened to the men in the photos. When the groups finished reading, I gave them a handout with three columns—Facts, Emotions, Images—and asked them to write at least four words under each heading. I explained that the images could be from their imaginations. “Even if the article doesn’t mention blood-stained cement, that might be something that comes to your mind as you read the article. Think about the pictures your mind sees as you read the article and write them down.” For the list of emotions, I told them they could write their own emotion or an emotion that they believe people in the article felt. “So, when I read about Henry Dumas, I felt shocked. I’m going to write ‘shock’ on my chart. I’m also going to write ‘frustrated’ because I think his family might have felt that way.”

Students went back to their articles and searched for compelling facts, strong emotions, and vivid images. Shavon was in the group that read about Martin. Under Facts she wrote “acquitted” and “a voice can be heard screaming for help.” Fania, who studied Diallo, listed “betrayal” and “resentment” under Emotions. Lakeesha, who focused on Bell, wrote “a wedding dress hanging on a hanger” and “a child standing at a casket” under Images.

After they filled out the charts, I asked for a representative from each group to share what they learned. “Give us at least three important facts,” I said. I wrote on the board under the picture of each person. “Make sure you copy this list in your notebook,” I told the class. I wanted to keep them engaged, and I also needed them to have this information for the poems they would be writing.

Seeing the faces of five black men who had been murdered side by side, with facts about their lives written under their names, was sobering. Once all groups had shared, we had a class discussion. “What did you learn? What more do you want to know?”

Sami wanted to know why this kept happening. Jason wanted to know why, in the cases of Diallo and Bell, there was such excessive force. “I mean, 41 bullets being shot is just not right!”

I asked students to share how they felt. I took the first risk and shared that I felt angry and sometimes hopeless. That I cried when I heard the verdict because I thought about my 17-year-old nephew and how it could have been him walking home with snacks from a corner store but never making it. Maria said she felt sad. Jeremiah shared that it made him afraid sometimes. Fania told the class: “It just makes me angry. It makes me so angry.”

Poetry Holds Rage and Questions

It was important to me not to censor students, but to welcome their emotions into the space. Just as I invited their boisterous laughter, their hurt was allowed here, too. Even if that meant tears. I believe young people need space to learn and practice positive ways of coping with and processing emotions. Art can provide a structured outlet for them to express how they feel.

I wanted them to know that poetry could hold their rage and their questions. The first poem we read was “Forty-One Bullets Off-Broadway.” I played the audio poem and students read along. As I had asked them to mark up their articles, I asked them to do the same on the poem. “I’d like you to think about when Willie is using facts from the article and when he is using his own imagination.”

Usually, as a ritual, we give snaps after a poem is shared in class, following the tradition of poetry cafés. But after listening to Perdomo’s poem, students clapped.

Before discussing the poem, I asked them to number the stanzas. “I’d like us to talk like poets, OK? So name the stanza you’re referring to and, if you notice any literary devices that Willie is using here, we can talk about that, too.” We noted when he used a fact from the case. “In the second stanza, he mentions the exact number of bullets,” Maisha pointed out.

Jeremiah read from stanza four:

Before you could show your

I.D. and say, “Officer—”

Four regulation Glock clips went achoo

and smoked you into spirit

He recognized that Diallo reaching for his wallet was factual and noted Perdomo’s use of personification in making a gun sneeze. He also noticed that Perdomo used his imagination to describe the “bubble gum-stained mosaic” floor where Diallo’s body fell.

Night, for Henry Dumas

By Aracelis Girmay

Henry Dumas, 1934-1968,

did not die by a spaceship

or flying saucer or outer space at all

but was shot down, at 33,

by a New York City Transit policeman,

will be shot down, May 23rd,

coming home, in just 6 days,

by a New York City Transit policeman

in the subway station singing & thinking of a poem,

what he’s about to eat, will be, was, is right now

shot down,

happening yesterday, happened tomorrow,

will happen now

under the ground & above the ground

at Lenox & 125th in Harlem, Tennessee,

Memphis, New York, Watts, Queens.

1157 Wheeler Avenue, San Quentin, above which

sky swings down a giant rope, says

Climb me into heaven, or follow me home,

& Henry

& Amadou

& Malcolm

& King,

& the night hangs over the men & their faces,

& the night grows thick above the streets,

I swear it is more blue, more black, tonight

with the men going up there.

Bring the children out

to see who their uncles are.

This poem originally appeared in Girmay, Aracelis. 2011. Kingdom Animalia. BOA Editions Ltd.

The next poem we read was Girmay’s “Night, for Henry Dumas.” Just as we did when discussing “Forty-One Bullets Off-Broadway,” we talked about where Girmay used facts, where she used her imagination. Students liked how she referenced Dumas’ science fiction writing by saying he did not die by a spaceship. Most of them had underlined the moment of the poet’s imagination when she writes that Dumas died “in the subway station singing & thinking of a poem/what he’s about to eat.”

We talked about the different approaches each poet took. “Willie Perdomo focused on one incident and took us into Amadou Diallo’s story,” Lakeesha said. “Aracelis Girmay wrote about Henry but also talked about other black men who have been murdered.”

I asked the class: “What do you think the phrase ‘happening yesterday, happened tomorrow’ means?”

Maisha touched the puzzle at her table, moved the pieces even closer together. “I think she’s saying that it happened in 1968 and in 2008 and in 2012—”

“And it’s probably going to keep happening,” James blurted out.

I asked him why he thought that.

“Well, there was Emmett Till,” he said. James was in my class last year when we studied Marilyn Nelson’s “A Wreath for Emmett Till” and watched excerpts of Eyes on the Prize. I was glad to see him making connections to previous lessons. “And in her poem, I think that’s what she’s saying. It happened way back in the day and it happens now and it will continue to happen everywhere.”

“Where do you see that in the poem?” I asked.

“This part,” Jason said. He read the lines to the class:

under the ground & above the ground

at Lenox & 125th in Harlem, Tennessee,

Memphis, New York, Watts, Queens.

1157 Wheeler Avenue, San Quentin, above which

sky swings down a giant rope, says

Climb me into heaven, or follow me home

Lakeesha noted Girmay’s list of black martyrs. “There could be so many names added to that list,” she said.

“How does this make you feel?” I asked the class.

“It makes me want to be careful.”

“It makes me worry about my brother.”

“I feel really angry because it isn’t fair and it’s not a coincidence that this keeps happening.”

Then I asked: “Why do you think Aracelis Girmay and Willie Perdomo wrote these poems? Does it change anything? What’s the point?”

“It makes people aware of what’s going on.”

“I think the point is to make people remember. If people don’t write their stories they could be forgotten.”

“And it honors them.”

Writing from Facts, Emotions, and Images

With that, it was time to write. “You can choose to write your poem like Willie did, and focus on one person. Or you can include the stories or names of others, like Aracelis.” I told them to be sure to use the brainstorming chart to help them with writing their poem. “Your poem should include at least three facts, three emotions, and three images from your chart.” I also gave them options for point of view. “You can write in first, second, or third person. You can write a persona poem in the voice of one of the people involved in the story—for example, you can be Oscar Grant or maybe his daughter. You could even speak from the bullet’s perspective or the ground.”

I wrote line starters on the board, but most students didn’t use them. They had a lot to say and already knew how they wanted to craft their poems. Since that day, I have taught this to racially diverse groups of students, as well as to professionals who work with young people, including teachers, counselors, and administrators at the college level; the words have spilled out of almost everyone.

I was deeply moved by the poetry my students wrote. For example:

Never Written

by A. M.

for Henry Dumas1968, underground,

day or night,

coming or going,

under the eternal florescent

flicker of subway lightsthe clamor of wheels,

crackle of electric current

maybe muffled the shooting

sound that silenced.One cop’s “mistake”

two boys now to forever

wait for their father’s face.A mind full of memory and make believe,

stretched from sacred desert sands

to sci-fi space and mythic lands,

spilled out, running thick

on worn concrete spansas subway doors open and close

empty cars rattle ahead

blank pages blown behind

nothing but another man’s

black body laid down

in haste and waste.

For All of Them

by L. V.Who scrubs the blood-stained train track, tile, lobby, car, sidewalk?

Who tears down the yellow tape?

Who sends the flowers and cards?

Who sings at the funeral?

Who watches the casket sink into the ground?

Who can get back to their normal life?

Who is holding their breath waiting for the next time?

Who takes a stand?

Who demands justice?

Who knows justice may never come?

Who keeps fighting anyway?

Who fights by protest?

Who fights by teaching?

Who fights by writing a poem?

Who fights by keeping their names alive?

After students revised their poems, I encouraged them to take a small action. “The first brave thing you did was make yourself vulnerable enough to write this poem. Now what are you going to do with it?” I asked. “Remember the reasons you said it was important for poems like these to be written. How can you share your poem to get it out into the world?” We made a quick list that included posting the poem on Facebook, tweeting a line or phrase from the poem, recording the poem and posting the video, reading the poem to a teacher, parent, or friend.

Later in the semester, a few students shared their poems at our open mic, when we invited parents and the community to witness the art their young people had created. Some students shared their poems through social media outlets. I encouraged them to not let this just be an assignment but something they took out of our classroom. I challenged them to pay attention to the news, to continue to use their pens and their voices to respond to what is happening in their world.