Boys in Dresses

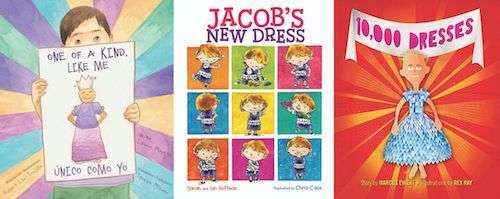

One of a Kind, Like Me/Unico como yo by Larin Mayeno // Illustrated by Robert Liu-Trujillo // Blood Orange Press, 2016

Jacob’s New Dress by Sarah and Ian Hoffman // Illustrated by Chris Case // Albert Whitman & Co., 2014

10,000 Dresses by Marcus Ewert // Illustrated by Rex Ray // Triangle Square, 2008

“I’m going to be a princess, just like her.”

I was reading One of a Kind, Like Me/único como yo. It was after recess, story time for my class of 2nd- and 3rd-grade bilingual students. Josue raised his hand. “Is Danny a boy?” he asked.

“Yes,” I said. “Danny is a nickname for Daniel. Isn’t there a 5th grader named Daniel on your bus?”

The students nodded, they knew Daniel. Josue raised his eyebrows and giggled quietly.

I was a little surprised at Josue’s reaction. He is one of my 3rd graders and had been in my class last year, too, when we read I Am Jazz, about transgender reality star and video blogger Jazz Jennings. It was a class favorite. We never split up into groups according to assigned gender and the students know I will challenge them if they label anything “for boys” or “for girls,” so they don’t.

But I didn’t say anything yet. I just continued to read the story: Danny wants to be a princess for the school parade. He asks for a purple dress with puffy sleeves and ruffles. Danny and his mother go to a thrift shop to find a dress.

Jasmine raised her hand.

“Yes, Jasmine?”

“Danny is a boy or a girl?” she asked.

“He is a boy,” I repeated, although now I was unsure if that was the best response. The book uses he/him/his to describe Danny, so I guess it’s fair to say he’s a boy, right?

As the story continues, Danny gets his dress and he’s excited to bring it to school.

“What do you think will happen next?” I asked.

“They’re going to laugh at him,” said Josue.

I’m sure that’s what my students expected, because that’s usually what happens in picture books that try to teach empathy — someone is different and they get picked on. And that is what happens in Jacob’s New Dress, another story I read to the class. Jacob wears a dress to school and has to deal with students who feel uncomfortable with it. I like Jacob’s New Dress because in some ways it is as much for adults as it is for children. The adult characters in the book are realistic, but they model positive ways to affirm our children. For example, Jacob’s mother tells him, “There are all sorts of ways to be a boy.” Although Jacob’s father isn’t jumping up and down at the idea of his son wearing a dress to school, he concedes, “Well, it’s not what I would wear, but you look great.” Jacob’s teacher in the story is also positive about his dress.

There is one place the story falls short. Jacob stands up to the bullying classmate on his own, without the support of an adult or the help of a friend. But that makes Jacob’s New Dress an opportunity for teaching critical literacy: What could Jacob’s teacher have said? What could Jacob’s friends have done?

At a few points the book describes how Jacob’s body is feeling. I ask my students how they think Jacob’s antagonist is feeling. Might he feel confused? Uncomfortable? What else could he have done with those feelings?

The main character in 10,000 Dresses, Bailey, dreams of dresses. One at a time, Bailey’s mother, father, and brother tell Bailey that she is a boy and cannot have a dress. Bailey finally finds a friend who respects her as a girl and together they dream up dresses.

The use of pronouns in this book is important, but needs discussion in class. The narrator refers to Bailey as “she,” because that’s how Bailey thinks of herself, even though Bailey looks like a boy and that’s what her family considers her. Who is right if the family says Bailey is a boy but Bailey feels she is a girl? I encourage teachers to read the book over a few times and think about how to facilitate this conversation before sharing the book with students.

These three books work well together to generate discussion and deepen children’s perspectives on gender. Danny and Jacob are boys who want to wear dresses. Does that mean they are questioning their assigned gender? We don’t know. Maybe, but the stories are more about questioning gender roles and accepting choices outside our comfort zones. Bailey’s story is clearly about gender. Although Bailey feels inside that she is a girl, her family members insist she is a boy.

One of a Kind, Like Me/Único como yo is the story that I’d read first with a new group of students. The storyline is simple and joyful; there’s no one arguing with Danny or telling him he is wrong. It is also one of the few bilingual stories I have found with a gender-independent character.

Together, these books contribute to a library that affirms that children should be able to wear whatever they want, regardless of assigned gender. Classroom libraries need collections of books on topics and issues, not tokens. That’s as true about gender as it is about immigration, the Civil Rights Movement, scientists of color, Muslim families, and other critical issues. Providing multiple books on a similar topic reinforces the message I repeat in my classroom: “Be who you are. All are welcome here.”