Girls Against Dress Codes

Illustrator: Alaura Seidl

“Ugh, Dress Codes!” The title of one of 15-year-old Izzy Labbe’s SPARK Movement blog posts encapsulates what I’ve heard so many girls say they feel about their middle and high school dress codes.

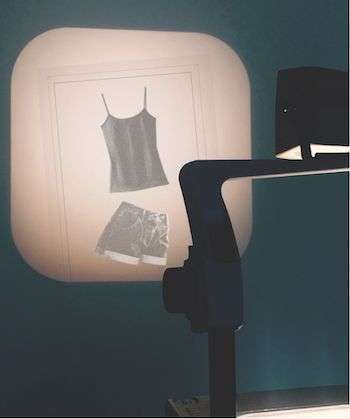

Izzy wrote her blog after years of frustration, beginning in early middle school when she began to notice girls’ bodies become objects of adult interest and surveillance. She honed her critique as part of SPARK Movement, an intergenerational girl-fueled activist project I co-founded in 2010. In her central Maine high school, Izzy and her friend Hannah formed the school’s first-ever Feminist Club. On the top of their list was a challenge to the terms of a dress code that penalized girls for wearing shorts and spaghetti-strap tops. After reasoned conversation with administrators failed, club members quietly posted dozens of 8.5 x 11″ sheets of white paper with large black print on school bulletin boards: “Instead of publicly shaming girls for wearing shorts on an 80-degree day, you should teach teachers and male students to not overly sexualize a normal body part to the point where they apparently can’t function in daily life.”

Izzy is now a first-year college student, but just this spring another Maine girl, 6th grader Molly Neuner, made national news for challenging her school’s dress code. Like so many before her, she joined a coalition of girls across the country using the Twitter hashtag #iammorethanadistraction. Reading her story, two things strike me: This issue is not going away and most adults don’t see the gift the issue offers.

Protests against dress codes get to the very heart of what it means to be an adolescent girl. It’s more than a generational claim to personal identity. Dress codes are a stand-in for all the ways girls feel objectified, sexualized, unheard, treated as second-class citizens by adults in authority — all the sexist, racist, classist, homophobic hostilities they experience. When girls push back on dress codes they are demanding to be heard, seen, and respected. This means it’s a moment primed for intergenerational engagement and education.

But too often, only two types of adults appear: administrators under fire for defending their schools’ policies and moms complaining about the shaming their daughters have endured or the school days they’ve missed for dress code violations. Where are the teachers who see the possibility for meaningful conversations about the development of institutional policies, about freedom of speech and choice, about democracy? How about those who see the opportunity to encourage critical thinking about cultural differences or the chance to examine the impact of media and pop culture on gender identity or the influence of rampant marketing and consumerism?

In response to this vacuum of adult engagement, girls are having these conversations without us. Most aren’t asking schools to eliminate dress codes altogether. They simply want policies that are relevant to their lives, policies that account for changes in clothing styles, that value identity development, gender expression, and cultural diversity. And they want and expect to be consulted.

They also say they want policies that are consistent and fairly applied. One study from the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity, for example, indicates teachers are more likely to discipline girls of color for minor offenses like dress code policy violations and are more likely to give them harsher punishments. Dress code policies can become just another example of a hostile school experience for girls of color, for trans girls, for girls living in poverty. Teachers who have not addressed their own unconscious biases (e.g., their tendency to judge a girl’s character by how she dresses), who have not confronted their internalized sexism or racism, who struggle with students who challenge the gender binary, cannot apply dress codes fairly. The best way to ensure a policy is applied fairly is diversity and bias prevention training for teachers and administrators.

It also helps to spend some time with students who have struggled with school dress codes and who think critically about bias, prejudice, and injustice. Here are a few things I’ve learned from listening to what girls say that make for a good dress code policy:

- “Each dress code rule must have an explanation,” Ejin Jeong writes in a 2015 blog post for SPARK Movement. “So much of the discontent with dress codes is that students often don’t understand why the rules are in place.” As a result, she says, dress codes “often feel arbitrary and unfair.” Bex Dudley, who blogs for Powered by Girl , tells me her school “tried to enforce ‘no brightly colored bras,’ when the material of the school uniform meant bras were visible. They were literally shaming girls for an ‘issue’ that they’d created.”

- A good policy applies to everyone; there are no gender-specific rules, no double standards. If girls can’t wear tank tops, neither can boys; if girls can’t show collarbones, neither can boys. In fact, girls want policies that have nothing to do with gender. “Have a plan for trans students without them having to ask for it!!” Bex exclaims. A transgender-friendly policy means anyone can wear a dress or a suit or earrings or makeup; anyone can wear their hair long or short. Formulated this way, a dress code can do more than prohibit; it can affirm and protect those who are already vulnerable, including transgender students and those who dress outside the gender binary.

- A good dress code is attuned to cultural and religious differences and allows students to do their hair (Afro, dreadlocks) and wear clothing (hijab, turban, yarmulke) that reflect these differences. And they include rules that protect students from those who appropriate or insult their religion or culture through clothing choices.

- A good policy is practical. It “gives some room for flexibility and expression,” Bex says, “like painted nails and colored hair.” And it maximizes student comfort. It accounts for changes in weather, allowing for seasonable clothing — e.g., shorts, sundresses, and tank tops when the temperature rises.

- Girls say they want policies that do not contribute to sexual objectification by making reference to their body parts or give adults the discretion to use dress code rules to body-shame. Izzy notices that teachers target girls with “curvier figures. . . . [G]irls aren’t getting in trouble for the length of their shorts,” she writes. “They’re getting in trouble for the shape of their bodies” and “it sounds like we’re blaming girls for other people’s negative reactions to their bodies. That’s misogyny! And it’s a problem when it enters classrooms and girls’ bodies are treated — by the staff, by boys, and by each other — as dirty, ugly objects that must be covered.”

- A well-crafted policy makes boys accountable for their behavior. Girls want school dress codes that make it very clear they are not responsible for how boys view them and that their clothing choices are not responsible for boys’ inability to focus or learn. Such assumptions excuse unwanted attention and harassment. It’s a short leap to blaming victims of sexual assault. “Can we throw the phrase ‘provocative clothing’ out the window, please?” Izzy asks. “Saying that clothing is provocative insinuates that it provokes sexual assault or rape or harassment, which is totally false. Harassers harass and abusers abuse regardless of clothing choices.” Instead of policing what girls wear, girls say they want schools to actively teach boys to respect girls and teach everyone to respect transgender students and those who are gender nonconforming.

- Good dress code policies give boys credit for being more than the sum of their hormones. When girls’ bodies are framed as “distractions” to boys, Gabby C. writes in a 2016 blog post for the FBomb, “they not only strip girls of their sense of self-respect and free-expression, but demean boys as incapable of controlling their basic urges.”

- A good policy clearly prohibits public shaming, which means adults don’t make girls kneel in front of classmates to assess skirt length or pull out a measuring tape in public to prove a strap is too narrow. Administrators don’t make an example of those who violate the dress code by forcing them to wear baggy T-shirts emblazoned with “dress code violator” like a scarlet letter. Correcting and shaming are not the same thing.

- A good dress code policy addresses the realities of poverty and social class. Some students wear what they can afford and what’s available to them. A short skirt or tight top are not necessarily attempts to ignore school rules. Dress codes can become a way to target and shame students already struggling with hypervisibility that comes with not wearing the latest styles or the most popular brands, much less clothing that fits well.

- A good policy does not send those who violate the rules home from school. There is no logic to a policy that takes away a girl’s right to education because her skirt is too short. “What’s more distracting, my shoulders or the fact that I just missed an entire history lesson?” Ejin asks.

In truth, most everything useful I’ve learned about girls I’ve learned from girls. On the surface, this isn’t an especially profound statement. But as I look around at the ways adults talk about girls, dismiss what girls know, blame them for the symptoms of societal injustice in all its intersectional forms, create barriers for some and soft landings for others in the guise of concern and protection — I think it’s radical to listen to girls and trust them as the experts on their own experience.

However well-intentioned, dress codes are a perfect example of an educational policy that puts compliance before learning; pressures and demands before support; a top-down bureaucratic solution created by adults at the expense of the time and effort it takes to really listen to and learn from students. And if girls are not heard, we should encourage them to advocate for their right to protest if need be. We can’t say we want girls to have high self-esteem, to take risks, to lead, and then dismiss or punish them when they take this issue on.

With dress codes, we can see up close and personal what it means for girls to struggle in ways that release imagination and hope for something new. The safe and affirming spaces we offer, the questions we pose, the options we create together with students, are catalysts to critical consciousness, to what Maxine Greene calls “wide-awakeness,” and to the possibility that their passionate and forceful reactions to unfairness and hurt will unfold in ways that better their lives going forward.

As Gabby writes for the FBomb, “Girls who take issue with these rules aren’t blindly rebelling, but truly advocating for their right to be heard as sentient subjects rather than passive objects.”

It’s time we listened.

References

- Darling-Hammond, Linda. 2005. Policy and Change: Getting Beyond Bureaucracy. Extending Educational Change: International Handbook of Educational Change, ed. by Andy Hargreaves. Springer.Ê

- Rudd, Thomas. 2014. Racial Disproportionality in School Discipline: Implicit Bias Is Heavily Implicated. The Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at The Ohio State University.