Preview of Article:

Gay Issues, Schools, and The Right-wing Backlash

Chasnoff and Cohen aren’t satisfied with the liberal compromise which kept gay issues pigeon-holed as the purview of high school teachers and health classes. They show that gay issues are ubiquitous in the lives of children from television talk shows and movies aimed at children, to playground slurs and hallway graffiti. They insist that the reality of children’s lives be confronted in classroom pedagogy.

Yet most educators gay, lesbian, bisexual, or heterosexual who are grappling with these issue do not teach in the large urban centers (New York and San Francisco) or liberal college towns (Cambridge or Madison) featured in It’s Elementary. They work in places like Salt Lake City, Utah, Elizabethtown, Penn., or Colorado Springs, Colo. Lesbian and gay issues play out very differently in these locations than they do in San Francisco or Madison. Consider:

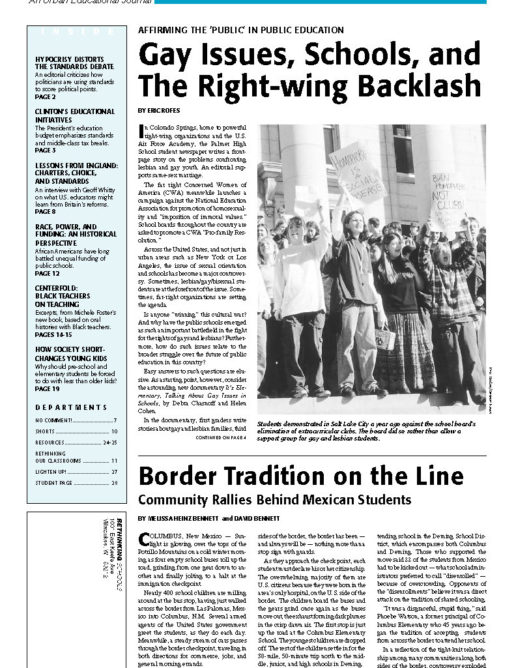

In response to the formation of a gay-straight alliance to provide peer support to lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth at Salt Lake City’s East High School, the school board banned all student clubs and associations not formally tied to school curricula. Banished are groups ranging from hockey and mountain bike clubs, to Native American and Polynesian associations, to the school’s Key Club.

Inspired by a “pro-family” resolution drafted by Beverly LeHaye, president of Concerned Women of America, the school board of Elizabethtown, Penn., adopted a resolution condemning various family forms including single-parent families, extended families, and lesbian and gay families. Despite student walkouts and community-wide protests, the board has refused to reconsider its position. It recently proposed an expanded anti-gay policy stating that “the curriculum will not promote or encourage same-sex sexual relationships or orientation.” The board has received support from both Concerned Women of America and the Rutherford Institute, a far-right legal advocacy group.

In October, 1996, the Palmer High School newspaper included two student-initiated articles about gay issues, a front-page story on the trials facing lesbian and gay youth in a hostile culture, and an editorial supporting same-sex marriage. Immediately after publication, the local Christian right mounted a campaign demanding tighter controls on student publications. Colorado for Family Values, the group which initiated the state’s controversial anti-gay initiative (later declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court), jumped into the fray. Their effort is focused on getting school boards to “promote abstinence, affirm traditional marriage, and discourage promiscuity … in every aspect of student life.”</p