From Snarling Dogs to Bloody Sundays

Teaching Past the Platitudes of the Civil Rights Movement

“I’m not teaching about civil rights this year,” my colleague asserted.

“Not teaching about civil rights?” I responded. My teaching buddy and partner had teamed with me in tackling “controversial issues” at the second/third-grade level – AIDS, the “discovery” of America, and homophobia, to name a few. I couldn’t believe that she was not going to join me in planning the civil rights unit.

My partner explained that a parent of a child who was continuing in her second/third-grade combination class had objected to the unit on civil rights the previous year. “There was too much violence,” she had said. Her daughter had been frightened.

Knowing that I would miss our joint planning sessions and sharing of materials and ideas, I nevertheless decided to go ahead with the unit.

My own experience growing up in an exclusively white and economically privileged suburb of Milwaukee had isolated me from the issues of the Civil Rights Movement. When, as a high school student in the 1960s, I finally became informed in a U.S. history class about the events in the South and the segregation and discrimination in my own city, I was appalled. I started on the long road to try to better understand issues of racism and to do what I could to act on the inequities in our society.

Unlike the suburb I grew up in, my school attendance area is culturally, politically, and socially diverse. Over 50% of the students come from families of color, most of them low-income. There are also low-income and working-class white families, and a smattering of middle-class families from a new development.

I had previously received a generally positive response to the civil rights unit. Parents had shared resources, such as a battered but prized painting of Rosa Parks. One grandmother came in to teach us freedom songs and talk about her efforts in the 1960s to organize an NAACP chapter in Oklahoma.

My former principal and a few teachers had disapproved of teaching such deep and heavy issues to young children. However, I could recall only one negative comment from a parent: “Why are you still teaching Black History when it’s past February?” In fact, even though I generally started the unit on or around the observance of Martin Luther King’s birthday, related activities integrated into all subject areas extended past January and February and, depending on student interest and the depth of the projects, into the first few weeks of March.

I planned the civil rights unit within the context of a discussion of Human Rights and Children’s Rights, in honor of the upcoming 50th anniversary of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights, signed on Dec. 11, 1949. It was during that discussion that my students had agreed that among basic rights for children is the right “to not be judged by the color of our skin.” This idea was a logical lead-in to the Civil Rights Movement.

We began by reading biographies about Martin Luther King Jr. and gave him his due as a strong and gifted leader. But I also wanted to go beyond the platitudes often taught in elementary classes. I discarded worksheets in my files that summed up the Civil Rights Movement in simplistic language such as “Dr. King decided to help the Black people and white people get along better.”

One especially useful book was I Have a Dream, by Margaret Davidson, and for 14 days we read a chapter a day from the book. While written in clear and fairly simple language, the book goes way beyond others in its genre in the complexity of its coverage of the Civil Rights Movement.

We used a variety of books, videos, poetry, and music to follow the history of racial discrimination and segregation. We studied not only King but many other people who worked together to overturn unfair laws and practices, especially the children: Ruby Bridges, the Little Rock Nine, the children in the Birmingham children’s march, the students in the sit-ins, and Sheyann Webb, the eight-year-old voting rights activist in Selma.

Sections from the PBS documentary series “Eyes on the Prize” were invaluable in helping my students witness history. They were entranced by the 1957 footage of the nine Little Rock high school students who faced angry mobs as they desegregated Central High. They cheered when one of the students, Minniejean Brown, got so infuriated with the daily intimidation that she finally poured a bowl of chili on her harasser’s head. They watched with awe as the children in Birmingham, AL, in 1963 joined the protests against segregated facilities and then stood their ground even as they were being slammed against the wall by the power of the hoses held by Bull Connor’s firefighters.

My students were especially captivated by the story of the Birmingham children’s crusade. The class participated in a role play about how these high school students helped desegregate public facilities in the city.

Jerome, an African-American student with a gift for the dramatic, made a remarkable Martin Luther King. Imitating King’s style for oratory, Jerome addressed his classmates who were playing the children gathered in the church after their first encounter with police brutality. Repeating the lines I gave him from the book I Have a Dream, he challenged the crowd, “Don’t get bitter. Don’t get tired. Are we tired?”

The students’ role-playing the Birmingham children responded before I had a chance to give them their lines. “NO!” they shouted, standing up and shaking their fists.

A PARENT’S CONCERN

I was halfway through the unit, feeling good about how the kids were conceptualizing the conviction of the civil rights activists – as well as how their enthusiasm was extending into reading, writing, and math activities – when Joanne, one of the eight African Americans in the class, handed me a letter from her mom. The letter expressed opposition to the civil rights unit, pointing out that Joanne had never witnessed hatred and brutality toward Blacks. Joanne, she said, had “no experience with police and guns, snarling dogs, hatred, people who spit and/or throw soup at others.” Joanne felt afraid at bedtime because of the “true stories” she remembered from the books and movies.

I had anticipated that such issues might come up, and had tried to take steps to deal with the children’s reaction to the violence of racism. For example, before we began the Emmett Till section in “Eyes on the Prize,” we had discussed how scary some of these historical events were. Third-grade students, who had been exposed to some of the content the year before, shared some feelings of fear, but also affirmed that they wanted to learn more about what they had been introduced to in second grade. I assured the class that acts that the Ku Klux Klan and others had committed with impunity 30 years ago could not go unpunished in 1999.

I also knew I couldn’t pretend that racial hatred is a thing of the past, however. I knew that many of my students were aware of the racist acts of violence reported in the national news. I also knew that many encounter racist name-calling or other biased acts in school and in their neighborhoods.

I hadn’t seen signs that Joanne had been upset; in fact, her contributions to class discussions revealed a fascination with the topic. However, I was glad that Joanne’s mom had communicated to me a problem that I might have missed.

As Joanne’s mom had suggested, and in fact, as I would have done anyway, I took Joanne aside to talk with her. She said that the story of Emmett Till had bothered her, but that the rest had been okay. Cheerful and positive, as usual, Joanne dismissed my concern, and said she wanted to learn more.

I asked her to let me know if something was troubling her. I decided to watch her closely for signs of distress or withdrawal and to ask her frequently if she was doing all right. I also said she had the option to leave if the content disturbed her. But then I received another communication from her parents that she was to be excused from all books, movies, and poems that showed hatred toward Blacks.

I thought back to my teaching partner’s reason for not teaching about the Civil Rights Movement. I thought of a few other parents and one other teacher (all middle-class African Americans, like Joanne’s mom) who had told me that they didn’t want slavery or racism taught about in schools because that was all behind them and they didn’t want it dredged up. It was too painful. It was over. It made them out to be victims. Joanne’s mom said that she wanted her daughter to know only the positive parts of the movement- the love and the happiness – not the snarling dogs and hatred toward Blacks.

I was in a quandary. Was it possible to teach in any depth about the Civil Rights Movement without including the violence and the racism? On the other hand, as a white teacher, was it presumptuous of me to decide to teach something that offended an African-American parent? I knew that I couldn’t put myself in her or Joanne’s shoes. I can’t know what it is like to be a racial minority is this country. And as a parent of three children, I know that parents have insight into their children that a teacher might lack.

I respect the right of parents to communicate their concerns and, if possible, I try to address them by altering what I do in the classroom. However, I knew that my obligation went beyond Joanne and her parents. I needed to think about what was best for all my students.

ASSESSING THE REACTIONS OF THE STUDENTS

I watched my students carefully. It soon became apparent that my African-American and biracial students (9 out of 25) were gaining strength and self-confidence during the unit. They were participating more frequently in class, sharing information that they had learned from the many books available in the class and relating what they were learning about the Civil Rights Movement to their own lives.

I knew I had to think of Joanne. But I also had to think of Keisha, Jasmine, Monique, and Jerome.

Take Keisha, who had often drifted off to sleep through our other units and when called on would ramble. During the unit, she suddenly found her voice. In preparation for our enactment of the Birmingham children’s march, for example, I talked to the class about what it meant to be “in character” in a drama. I told them to think about how they would feel if they were the people marching for their rights.

“I know,” broke in Keisha, “You would be serious. You wouldn’t be acting silly or nothing, because this is about getting your freedom. And you are marching for your mother or your father or your sister or your brother or for your children or your grandchildren, not just for yourself.”

The next morning, Keisha brought in a friend from another class. “I have something to share,” Keisha said. “Yesterday, at the Community Center, LaToya and me made up a speech, like Martin Luther King.”

Her friend pulled out a rumpled sheet of paper and they proceeded to present their speech to the class:

Keisha later chose to do her human rights biography project on Harriet Tubman. She read all the books she could find on the topic and wrote her longest, most coherent piece in her journal on Tubman. And once, when the class was having a particularly difficult time settling down, Keisha yelled out, “Hey, would you all be acting like this if Martin Luther King was here?”

Jasmine, a biracial girl with a long history of discipline problems at the school, took to heart the story of six-year-old Ruby Bridges. (See biographies, right.). Jasmine surprised me one morning with a life-sized portrait of Ruby Bridges that she had made in the after-school program by taping together smaller pieces of paper. She wrote about Ruby Bridges in her journal and in a letter to Wisconsin Governor Tommy Thompson on another topic, she asked, “Have you heard of Ruby Bridges?”

One day, Jasmine approached me in confidence, “Kate, you might not know this, because it’s a secret, but I’ll tell you something I’ve been doing.”

“I’d like to know, Jasmine,” I responded, expecting a confession of some wrong-doing.

“Well, Kate, sometimes, when I’m sitting at my table, I just pretend I’m Ruby Bridges. I pretend that the other kids sitting at my table are those people yelling at me because I’m Black and they don’t want me in their school. And, just like Ruby, I ignore them and just go on doing my work. I do it real good, just like Ruby. I was doing it just before at math time.”

And then there were Monique and Jerome. Previously two of my biggest trouble makers, during this unit they became the two I could count on to be on task for reading, writing, and other activities. Monique, who had previously disrupted numerous group discussions or cooperative projects, suddenly became the model student: “Shhhhh, everybody!” she’d admonish. “I want to hear this!”

Jerome found a connection from home. “My mom told me that we all need to learn about this because it could happen again,” he said. He told the class about when the people next door to his apartment house had put up a sign to prevent kids from cutting through their yard on their way to school. The sign had said, “Private. Stay out of our yard. No niggers.”

Many of the other students talked about how they, too, would have been discriminated against if they had lived in the South during Jim Crow. (I also had four Hmong students, one Cambodian American, two Filipino Americans, two born in Mexico, and one with a Mexican-Indian grandparent.) “I would have had to use the ‘colored only’ drinking fountain because I’m part Filipino,” Anita would remind the class. At the drawing table I heard one girl say, “You know, we would all have been discriminated against, because I’m part Mexican, you are Hmong, and you are both Black.”

I also watched the reactions of the European-American students. There were fewer white kids than children of color in the class and, although we had learned about many brave white activists, the whites were definitely not shown in a positive light in most of the material. I watched to see if the European Americans were engaged in our discussions and if they showed any signs of discomfort. Chris was tentative at first, hanging back, sometimes fooling around with another white boy. But then he started to participate more and more in the discussions and role-plays. As we were watching a video, “My Past Is My Own,” in which a white teenage gang assaults the Black students at a lunch counter sit-in, Chris moved close to where I was sitting.

“I don’t like this part,” he confided in me. “If those kids were friends of mine, I’d tell them, ‘Hey leave them alone. What you’re doing isn’t right.'”

The next day, Chris decided to write a letter to Rosa Parks relating his admiration for her courage.

Chris and many of the other white kids in our school come with attitudes that are the products of the racism that divides our neighborhood. I came to the conclusion that they, as much as, or even more than, the children of color, needed to hear the story of the racial hatred and the saving power of a nonviolent movement. There may come a time when they find the courage to say, “What you’re doing isn’t right.”

Despite the positive changes I witnessed in many of my students, the opposition of Joanne’s parents kept nagging at me. We kept in touch through notes and conversations. I heard, on the one hand, that they supported what I was doing; yet Joanne was still to be kept out of all activities related to the unit. I talked over the situation with colleagues and friends, including the principal, who encouraged me to go on with the unit. (In the first grade, a parent had complained to the principal that the teacher had not gone into enough depth in presenting the history of civil rights.)

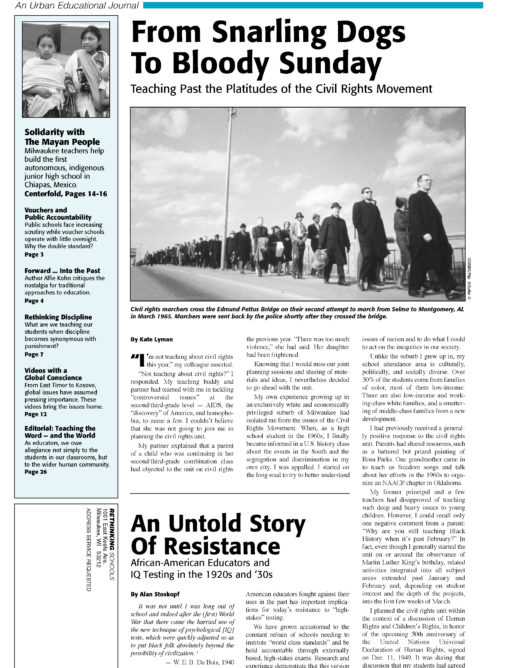

I also spoke with an African-American man, the grandfather of a student, who had presented to my class several years ago. He had proudly brought in a huge photograph of the Edmund Pettus Bridge and had told how he joined the voting rights march on “Bloody Sunday,” March 7, 1965, and crossed that bridge only to be attacked by local and Alabama state police officers armed with weapons and tear gas.

I invited him back to speak to the class and also asked his opinion on my dilemma, sketching out the objections to the civil rights unit. His voice, heretofore somewhat soft and distant, became strident.

“Hey, that’s what we were all marching for!” he said. “We were marching for the right for our kids and all kids to learn about the history of Black folks. And it’s not like it’s over and done with. They might try to keep their kid from knowing about it now, but sooner or later they’ll find out and then it will be a shock. Better to learn now what we were all fighting for!”

I decided to also ask the opinion of my students. I was finding it hard to put off questions of why Joanne was dismissed to work in the library each time we worked on the unit. Even though I assigned different work for Joanne, some members of the class were protesting that she was playing on the computers while they were working on their writing and reading. One day, when Joanne was out of the room, I told the class that Joanne’s parents objected to her learning about the Civil Rights Movement.

I also asked the class if they thought it was an important topic. The consensus was that it was “very, very important.” The reasons came out faster than I could record them: “So if that stuff happened again, we could calm down and be strong.”… “It might happen again and then we’d have to go and march.” … “The KKK is still alive and they don’t like Blacks and Filipinos.” … “It makes us smarter to learn about this, and then if we have kids and they wanted to learn about it, we could teach them.” … “When we go to another grade, we will know not to call people names like Darkie.” … “If you learn about it, you get to go to higher grades and get to go to college.”… “Dr. King, he was trying to tell us that we could have a better life.” … “We want no more segregation, no more fights, no more KKK burning down houses.” … “So it don’t happen no more.”

We went on with our work. At this point in the unit, the focus was on presenting a student-written screenplay of “Selma, Lord, Selma” (which in turn was based on the Disney television special). Not wanting Joanne to miss what was becoming an even more central part of our curriculum, I suggested to Joanne’s parents that they watch the tape of the television special. Since it was shown on “Wonderful World of Disney,” I figured I couldn’t go wrong there. I also gave them copies to read of the screenplay that the class had written. I again was told that Joanne could not participate.

The rest of the students, however, immersed themselves in the drama. Jasmine transformed herself into the role of Sheyann Webb, the brave eight-year-old participant in the Selma voting rights movement. She held her head high and sang “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round” with a voice pure in tone, perfect in pitch, and strong in conviction. Monique turned all her energies into not only acting the part of Rachel West, Sheyann’s friend, but also keeping the rest of the class on task and in role. Jerome continued as Martin Luther King, changing the words of his speech every practice but never failing to perform the part of the orator and leader of the people. It was clear that the play was cementing the history of the Civil Rights Movement in the minds and hearts of every student.

Several days before the final performance, Joanne’s parents approached me in the hall. They wanted her to participate, although they were concerned it might be too late. They never explained what had led them to change their minds. I knew that Joanne was feeling left out, especially since the class had also been working on their play in their music and movement classes.

Despite my earnest efforts to excuse Joanne to the library whenever we read or discussed material related to civil rights, Joanne, a very bright and curious girl, had not only managed to pick up a lot of information, but had also learned the songs in the play. Joanne took on her role as a voting rights activist in “Selma, Lord, Selma” as smoothly as if she had been practicing it for three weeks with the rest of the class. She not only marched to the courthouse, singing “Kumbaya” and demanding the right to vote, but she also participated in a slow-motion pantomime of the “Bloody Sunday” confrontation, as marchers attempting to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge were met with the troopers’ sticks, cattle prods, and tear gas.

After Joanne and the others recover from the violent attack and rise to the occasion of singing “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Me ‘Round,” this time with added significance to the words, Jasmine (Sheyann) narrates: “We were singing and telling the world that we hadn’t been whipped, that we had won. We had really won. After all, we had won.”

THE LESSONS OF SELMA

The Selma story instructs us that out of unspeakable violence and defeat can come resolution and victory. Out of Bloody Sunday came renewed participation and power in the Civil Rights Movement, resulting in the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the success of the second Selma to Montgomery march.

Can the Civil Rights Movement be taught without teaching about segregation, racial hatred, and violence? I don’t think so. It is against the backdrop of the fire hoses and the snarling dogs that the Birmingham children found their strength to sing, even as they were hauled off to jail. When Martin Luther King was denied the right to sit in the front of a shoe store or to play with his white friends, the seeds of his leadership were planted. It does not make sense to teach the Civil Rights Movement without teaching about the separate bathrooms and KKK. Furthermore, to do so wouldn’t be history. It would be a lie.

Despite the controversy my unit engendered, I did not regret my decision to proceed. Even though the behavior and academic focus of students like Keisha, Jasmine, Jerome, and Monique did not remain at that peak, they still remembered those weeks as the best part of the school year. And as we moved into learning about the struggles of other groups of people for equal rights, or as we talked about issues of justice and tolerance in the classroom, we always had the Civil Rights Movement to look back to for inspiration.

As Keisha said in her end-of-the-year evaluation: “I liked giving my speech in class about Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks, too. They fought for freedom and the right to vote. They are so cool to do that and march and give us freedom. [If they hadn’t done that,] me and you would not be together today and be learning.”