Preview of Article:

Fourteen Days SBAC Took Away

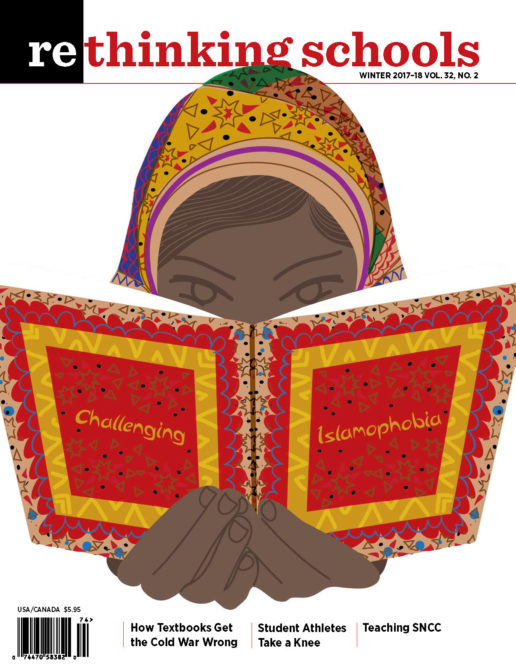

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert (christiane-grauert.com)

“Do I have to do this?”

Miguel pleaded with me. He hadn’t even logged in and sat at the computer, deflated. I nodded. I couldn’t get myself to feign a smile. Twenty-one 6th graders were sitting in the room — some with Spider-Man or a Ninja Turtle emblazoned on their shirt, a few who sported baseball caps with flat brims they carefully kept the original gold sticker on, girls who still wore colorful ball ponytail holders and beads in their braids and pigtails, and the girls who made sure to keep their lip gloss nearby. Twenty-one students — 11- and 12-year-olds. It was May and that meant SBAC time. The Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium. The Test.