For Students to Understand Today’s Violence in Palestine-Israel, We Need to Teach About Zionism and the British Empire

A small group huddled in the back of the classroom. “It all started with antisemitism in the Russian empire, with Jews being forced to leave,” said Zack. “Antisemitism led to Zionism — which is just a lot of people searching for safety and a home. The problem is that another huge group of people would be shunted out of the way, pushed to the corner.”

Zack, a 9th grader at Grant High School in Portland, Oregon, was trying to name a root cause of today’s humanitarian catastrophe in Palestine-Israel. Knowing something about Zionism helped him think about the origins of the conflict there.

Unfortunately, at the very moment students should be learning to think critically about Zionism, prominent voices want to shut down this inquiry. For example, in his recent influential Atlantic magazine article “The Golden Age of American Jews Is Ending,” Franklin Foer writes, “There’s a reason so many Jews bristle at the thought of anti-Zionism finding a home on the American left: Zionism can start to sound like a synonym for Jew” [emphasis in the original]. For Foer, criticizing Zionism leads to antisemitism, so we should stop talking about Zionism.

But we cannot understand the long history of oppression — of both Jews and Palestinians — if we abolish “Zionism” from our lexicon, and from our curriculum. Omitting Zionism from our classes makes it impossible to map the route that led to today’s horrific violence wracking Palestine-Israel. In fact, the origins of Zionism and the Zionist movement’s aim to transform Palestine into a Jewish country should be at the heart of any curricular attempt to probe the cause of today’s humanitarian catastrophe. (See my article in the spring issue of Rethinking Schools: “No, Anti-Zionism Is Not Antisemitism.”)

When my friend and colleague Suzanna Kassouf invited me to join her in teaching about the “seeds of violence” in Palestine-Israel, I wrote a hybrid mystery-mixer activity that takes students back to when the Ottoman Empire ruled Palestine, and Jews were beginning to flee pogroms — antisemitic violence — in Eastern Europe, and to when the Zionist movement began to partner with the British Empire.

Suzanna teaches five 9th-Grade Inquiry classes at Grant High School. Full classes, with about 30 students in each. With gentrification, Grant is whiter and more affluent than when I spent my first year teaching there in the late 1970s. Suzanna taught the “seeds of violence” activities to all five of her classes, and I joined her for three.

We led these lessons during the end of January and early February, as Israel’s assault on Gaza was unrelenting. In each class, we began by acknowledging that making sense of the violence depends on when one “starts the clock.” On Oct. 7, Hamas fighters attacked Israel and killed about 1,200 people and kidnapped 250 more. That attack triggered Israel’s current onslaught. But the violence did not begin on Oct. 7. I shared with students a Made in the USA tear gas canister and a handful of so-called rubber bullets — steel ball bearings with a thin plastic coating — that I brought back from Gaza when I’d stayed in the Jabalia refugee camp in late 1989 with Rethinking Schools editors Linda Christensen and Bob Peterson, on an educators delegation. The kids where we were staying in Gaza brought them home after school — they’d been fired into schools by the Israeli military. At the time, during the first Intifada, Gaza was fully occupied by Israel, and military vehicles patrolled the streets during shoot-to-kill dusk-to-dawn curfews, and soldiers regularly shot into schools during the day. But, Suzanna and I emphasized, the violence did not begin in 1989, any more than it began on Oct. 7.

We told students that we were going to do a mystery activity. We would try to solve What is the source of the violence in Palestine-Israel? And at the end of the activity, students would determine who or what they thought was at the root of today’s violence.

The heart of the lesson is a mixer role play in which students try to “become” one of 17 individuals whose lives touched — or were touched by — events in Palestine, covering the last years of the Ottoman Empire, roughly from 1890 to the British Mandate over Palestine in 1922. There is a lot of history to become familiar with, but students encounter much of this through reading people’s stories and meeting one another in character. As we told students: Much of what is going on today comes into focus when we encounter what unfolded in Palestine at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.

The Mixer

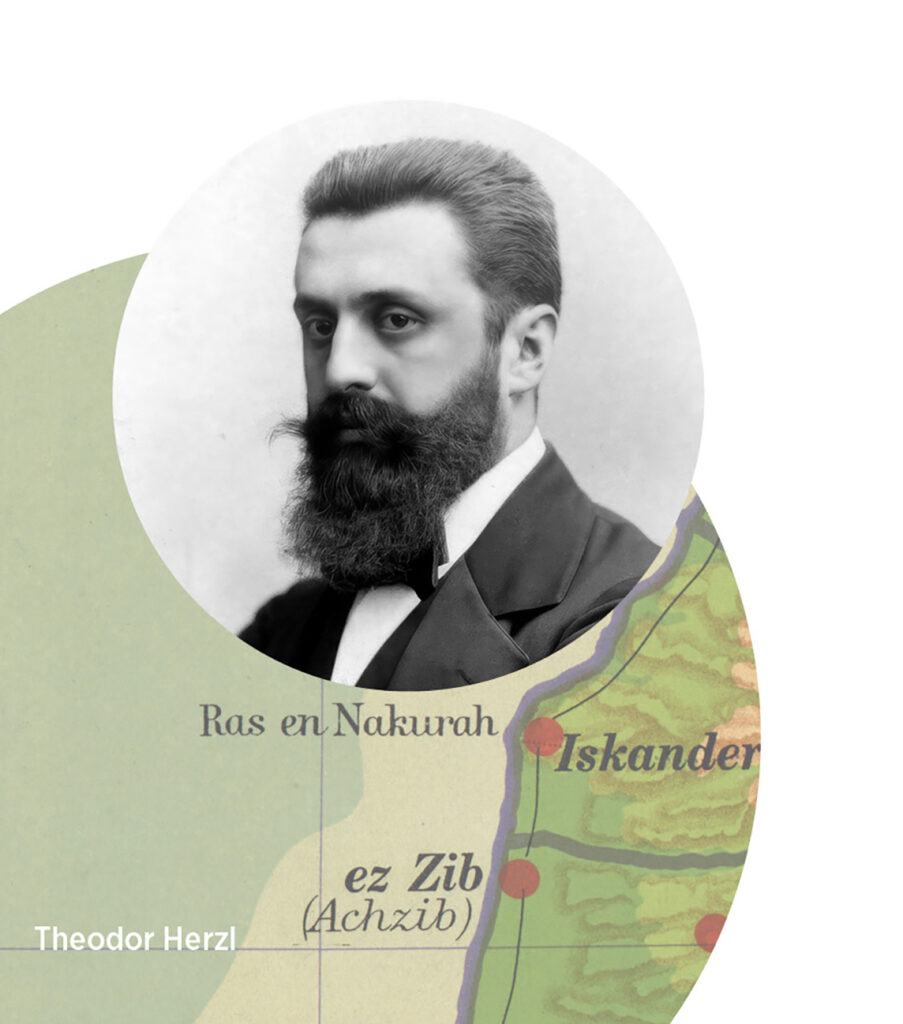

Some of the key individuals students meet in the mixer role play include: Theodor Herzl, the Viennese “father of Zionism,” who believed that the ubiquity of antisemitism made it futile for Jews to pursue assimilation in Europe, and proposed in his 1896 pamphlet The Jewish State, that Jews seek their own “home”; Pati Kremer, an activist with the socialist Jewish Bund in Russia who thought that Zionism’s flight-not-fight strategy was wrongheaded, and that what was needed was a class struggle organization to defend Jewish rights throughout Eastern Europe; Britain’s foreign secretary Lord Balfour, himself an antisemite as well as a Zionist, who sought to block Jewish immigration to Britain but promised in 1917 that the British Empire would support a Jewish homeland in Palestine; Joseph Baratz, an idealistic young Zionist who fled murderous pogroms in Russia to live collectively on a kibbutz in Palestine, but who had no room for Palestinians in his vision of an agrarian utopia; and Yosef Castel, a Sephardic Jew whose family had lived in Jerusalem for generations and saw the militant ethnic nationalism of the new Zionist arrivals as a threat to his Muslim-Jewish-Christian community.

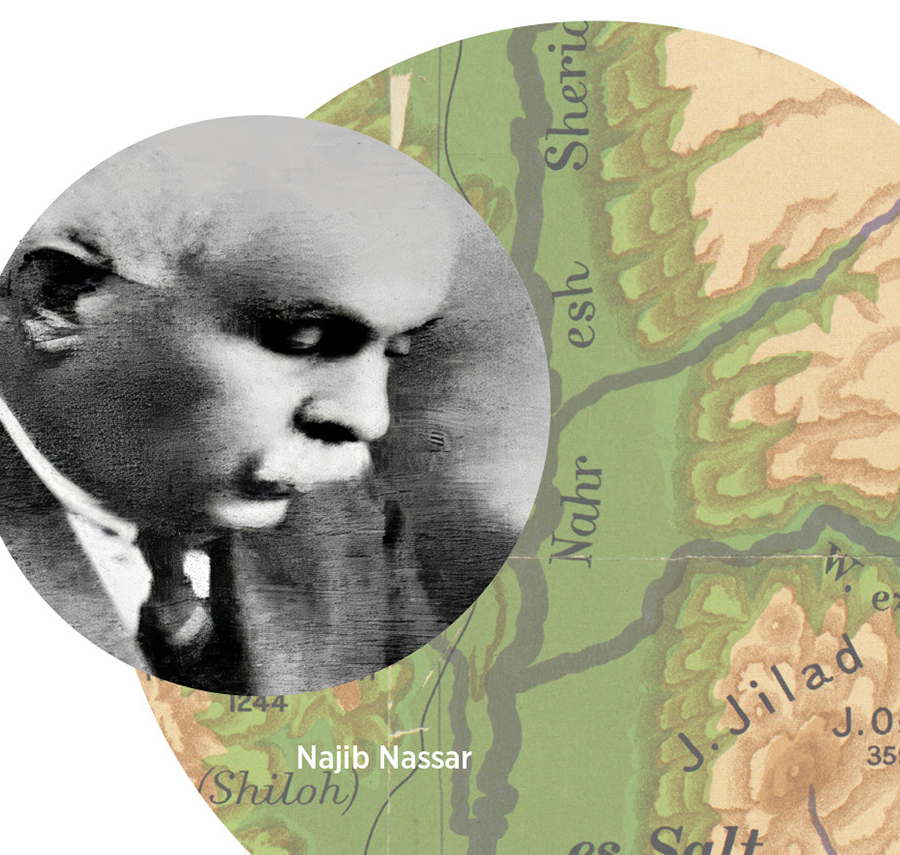

The Zionists’ land purchases in Palestine were problematic, as they bought land from people who held questionable title, hugely wealthy people like the absentee Beirut landowner Elias Sursuq, who “owned” and sold vast tracts of Palestinian peasants’ land to Zionist settlers. Palestinian peasants, like Mahmoud Khatib and Ahmed Sharabi, whose families had lived on the land for generations, resisted. And they had support from Palestinian journalists like ‘Isa al-‘Isa, editor of Filastin, and Najib Nassar, the Christian Palestinian editor of al-Karmil, who denounced the Zionist land purchases from absentee landlords, and the Zionist expulsion of Palestinian peasants. And they also had support from Palestinian Ottoman officials like Shukri al-‘Asali, the district governor for Nazareth, who risked his career and stood up for the peasants against corrupt land sales from rich landowners to Zionist settlers.

Before meeting these and other individuals in the mixer activity, Suzanna and I sought to familiarize students with key events and issues they would encounter in the mixer with some map work, locating Palestine, the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire, the Russian Empire, and some of the historical context on antisemitism, pogroms, Zionism, World War I, and the Balfour Declaration. [All student materials and detailed teaching instructions can be found at “Teaching the Seeds of Violence in Palestine-Israel” at the Zinn Education Project.]

We distributed a different role to each student. In every class, there were more than 17 students, so some students represented the same individual. The roles are fairly detailed, so we urged students not to rush, and to read them several times. Suzanna made recordings of each role so students could listen to them with headphones as they read.

We told students that we wanted them to internalize the information in their roles so that they could “become” this person in the mixer activity. We asked them to underline or highlight parts they thought were most significant, and to raise questions about anything that seemed unclear. After they finished reading, we asked them to turn over their role sheets and to write on: 1) What are the most important things to know about your character? 2) What fears does your individual have? 3) What hopes do they have?

We distributed name tags so that they could write their mixer name and their location or organization, and then handed out the mixer questions — eight of them — and read these aloud, asking students to star any question they might be able to answer for someone else. These included: “Find someone who supports Zionism. . . . Why do they support Zionism?” “Find someone who opposes or is critical of Zionism. . . . Why are they critical of Zionism or oppose it?” “Find someone who believes that they worked against injustice to make things more fair. . . . What did they do?”

We reviewed with students the mixer caveats:

- Speak in the “I” voice, as if you are this character. (I know that some teachers are reluctant to ask students to adopt other personas, but the activity works best when students speak in the first person, as their character.)

- Don’t adopt an accent or try to “act” the way you think your character would act. (Every role play risks stereotype. We reminded students that individuals in this activity were real people, and to approach them with respect.)

- Use a different individual to answer each question, even if one person’s story might apply to multiple questions.

- Take your time. It is not a race.

- Don’t group up. Just have one-on-one conversations. And, remember, you learn people’s stories by talking to them. Don’t exchange written roles.

- This is a get up-and-move activity. So if you are able, move throughout the classroom talking with different characters; don’t remain seated.

- And this is not The Twilight Zone; you can’t meet yourself. Some of you have the same character, so if you meet them, just pass on by.

In mixers, I always like to play a role. For one thing, it is more fun, but it also lets me take the temperature of an activity, and feel when it is winding down. In Suzanna’s classes, I played Elias Sursuq, the Beirut landlord whose family owned enormous parcels of Palestinian land, acquired by taking advantage of Ottoman laws that discriminated against poor and illiterate peasants. Through the years, Sursuq sold much of this land to Zionist settlers, who expelled Palestinian peasants whose families had lived there for generations. In the mixer, Sursuq was not a popular fellow among Palestinians. In a conversation with the student portraying the Palestinian journalist ‘Isa al-‘Isa I explained that the Ottoman Empire agreed that all my land sales were perfectly legal. She gave me a look of disgust and said sharply, “It may have been legal, but it was not moral.”

In all classes, the mixer was lively, even playful, but without being silly. It may seem paradoxical but the activity shows that although teaching honestly about the world requires us to surface painful history, our curriculum need not be similarly grim.

Debrief

It’s always helpful after a frenetic activity like this to allow students to pause and reflect on what they learned. We asked them to write: “Name two people you met who made an impression on you. It could be because you were angered, saddened, or delighted by their story — or because you learned something that was new to you. Who are the people? Explain your thoughts about them. It is fine if one of the people who impressed you was your own character.” Suzanna made all the role descriptions available in a Google Doc that students could access online, so if they needed additional details, they were easily located.

I loved reading what students wrote. They were diverse and insightful, and some were poignant. In the mixer, Maria portrayed Palestinian peasant Ahmed Sharabi, evicted from his land when it was purchased by Zionist settlers from the absentee owner. She wrote in part: “Another person who made an impression on me was Theodor Herzl. Our characters had very different views and I thought it was cool to talk. My character was a Palestinian struggling with Jewish settlers, whereas TH was firmly pushing Zionism as a Jew, believing it to be ‘justice’ for Jewish people. . . . I learned a lot when we were able to compare them side by side as actual humans. It’s also sad because you can see that most Jews just wanted safety and to not be mistreated. It’s horrible that the plan to make that possible included mistreating other people.”

The Jerusalem-based Sephardi Jew Yosef Castel made an impression on a lot of students. James wrote: “Yosef Castel’s story makes me feel hopeful because it shows that there can be peace between Palestinians and Jewish people. Their story shows peace with the two sides that could very well be implemented now. It is possible. We just have to work to make it possible.” No doubt, this feels like a distant hope, but learning the story of people like Yosef Castel can help inform that hope.

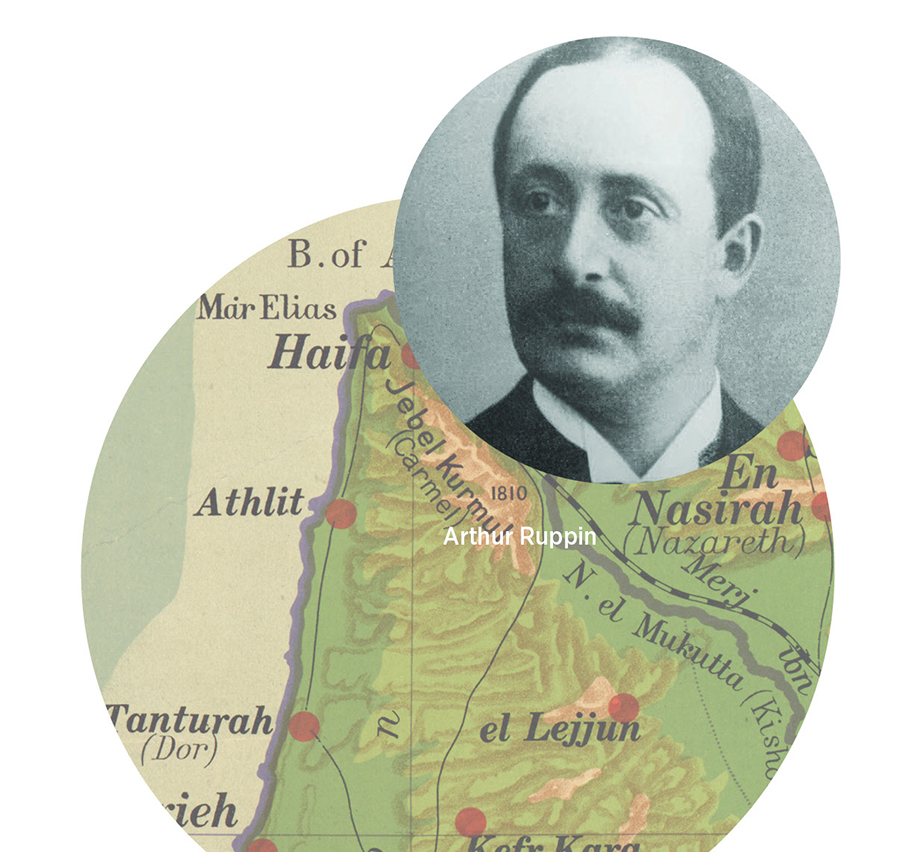

It is a dense history that students encounter in the mixer. But through conversations with one another, students seemed mostly able to grasp a bigger picture. But full disclosure: As so often happens in school, we suffered from unfortunate timing, ending the activity on the day before a weekend, with three full days sandwiched between the mixer and our mixer discussion. Thus our discussion the following week was not as fresh as had we been able to talk together immediately after the mixer. Suzanna and I were not exactly pulling teeth, but we did need to surface specific individuals in the discussion to remind students of who people were and how they connected to one another. We especially wanted students to recall that there were anti-Zionist Jews — like Pati Kremer and Castel — and antisemitic Zionists, like Lord Balfour. We also wanted to highlight Zionism’s fundamental aim of safety for Jews in a separate homeland, which students discovered in Theodor Herzl, Arthur Ruppin, and Joseph Baratz. And we wanted students to recognize that Palestine began as, well, Palestinian, and so surfaced peasants who lost their homes, like Ahmed Sharabi, Mahmoud Khatib, and Razan al-Barawi; as well as Palestinians who stood in solidarity with peasants, like Shukri al-‘Asali, Najib Nassar, ‘Isa-al-‘Isa, Musa Kazim al-Husayni, and Yusuf Diya al-Din Pasha al-Khalidi. And we wanted to remind students that these struggles were not just ethnic, but also grounded in social class — as the wealthy landowner Elias Sursuq was more than happy to sell Palestinian land to the Zionist new arrivals. His abuse of Palestinian peasants did not have religious or ethnic roots; to Sursuq et al., it was just business.

Solving the “Crime”

We returned students to our initial promise that we traveled back more than 100 years to make sense of today. We told students: “When we began the activity, we said that it was kind of like a mystery — that we wanted to figure out how the long-ago history of Palestine could help explain why there is so much violence today. As we said, we can call today’s violence the ‘crime.’ Obviously, this activity goes up only to the early 1920s, right after World War I, and lots happened between then and today. But let’s see if we can use that early period to think about responsibility for today’s violence. Which ‘seeds of violence’ were planted back then? What happened in that early history to put Palestine and Israel on a collision course?”

We distributed and read aloud a handout, “Palestine-Israel: Seeds of Violence Possible ‘Defendants.’” The possible “defendants” included all of the individuals in the mixer, but also broader defendants like the Ottoman Empire, the British Empire, antisemitism, Zionism, the Balfour Declaration, racism against Palestinians, exploitation by rich landlords — and also invited students to come up with “defendants” not included on the list. The assignment:

1) In your small group, choose three of these individuals, countries, empires, organizations, documents, or ideas that you think were “seeds of violence” planted in the late 19th century or early 20th century. Who or what in Palestine’s early history was “guilty” of laying the groundwork, or somehow contributing to today’s violence? You can choose from this list or suggest one or more of your own not included here. 2) Give at least three reasons for each of your choices of a possible “defendant.” 3) What else would you need to know about the history of Palestine-Israel to be more sure of your answer about the “seeds of violence” there?

We emphasized that we were not looking for “right answers.” We also encouraged them to describe how their “indictments” overlapped, and not to feel that they had to list each of these separately.

This small-group work to determine defendants was a delight to witness in the three of Suzanna’s five classes I was in. The groups’ conversations were animated, imaginative — and smart. Every group had the same “evidence” in front of them, but no two discussions were identical. One thing struck me right away. In most trial role plays — like “The People vs. Columbus, et al.,” for example — students have an easier time blaming individuals than systems or ideologies. But in the papers I read from three 9th-grade classes, 47 students named antisemitism as a key “seed” of today’s violence in Palestine-Israel, 29 named Zionism, and 19 accused the British Empire, sometimes all on the same paper. Those were the three leading defendants. But often, groups named three “defendants” culpable in interlocking ways.

Here is from a group in Suzanna’s end-of-the-day, period 4:

Antisemitism. Without antisemitism there is no Zionism. Without antisemitism Lord Balfour would not have created the Balfour Declaration and the British would not support the Zionists. Without antisemitism there would have been no pogroms, and Jews wouldn’t have felt the need to flee Russia. Zionism. Without Zionism, the Balfour Declaration wouldn’t have been issued. Without Zionism, Palestinian land wouldn’t have been bought out and Palestinians wouldn’t be forced out of their homes. Without Zionism, there would be less hatred of Palestinians. Ottoman Empire. Without the Ottoman Empire, the [1858] Ottoman land code would not have been passed. Without the Ottoman Empire, Zionists would not have been let in. Without the Ottoman Empire, Palestinians could have had independence in their own government. Without the Ottoman Empire, Palestinians could have kept their land.

Whether students landed on the Balfour Declaration, Theodor Herzl, Elias Sursuq, or antisemitism as defendants, students recognized that what began as Palestinians’ land ended with appropriation and domination. As one student wrote: “Zionists are invading and the core of Zionism is removing all non-Jews completely. It doesn’t try to cooperate at all. Just remove.”

Suzanna followed up by asking students to create a poster visualizing who or what was a “seed of violence” in Palestine-Israel. Suzanna’s assignment read: “Of the three ‘defendants’ that your group chose, now choose ONE and create a poster to demonstrate WHY this individual, country, empire, organization, document, or idea is guilty for planting the seeds of the violence we are seeing in Palestine-Israel today. You MUST draw on evidence from our learning the last three classes.”

These turned out to be wonderful — visually imaginative with diverse defendants, as in their small group work: “Antisemitism Planted the Seeds of Violence!” with flames growing up out of seeds; “British Empire Wanted,” with plants/crimes emerging from the “soil” of the British flag: “Not mentioning Arabs or Palestinians in the Balfour Declaration,” “No political rights,” “Evicted Palestinians.” One pair of students named the failure to imagine a decent society as the fundamental seed of the violence: “The Belief That No One Can Co-Exist Equally Is Guilty,” including an image drawn from the Sephardi Jew Yosef Castel’s role, depicting Muslim and Jewish mothers holding each other’s babies.

Throughlines

A student who decided on the “indictment” of Palestinian erasure identified a key throughline from past to present: “I think so much of this stems from the racism of not seeing Palestinians as people with rights.” In his essential book The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, Rashid Khalidi describes correspondence between the Zionist founder Theodor Herzl and Khalidi’s great-great-great uncle, the Ottoman/Palestinian scholar and official Yusuf Diya al-Din Pasha al-Khalidi, both of whom are included in the mixer. In his 1899 reply to a long letter from al-Khalidi, Herzl refers to the Indigenous people of Palestine as “the non-Jewish population in Palestine.” Herzl’s letter anticipates a similar eradication of Palestinians in the 1917 Balfour Declaration, which refers to “Jewish communities” as opposed to unnamed others: “existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine” — a denial of Palestinians’ humanity repeated five years later in the 1922 Palestine Mandate granted to Great Britain by the League of Nations. Of course, declaring Palestinians nonexistent became part of the Israeli playbook, perhaps most baldly stated by former Prime Minister Golda Meir in 1969: “There was no such thing as Palestinians.”

Then-Zionists’, now-Israelis’ partnership with empire is another throughline — an early “seed of violence” that has metastasized into what Palestinians experience today in Gaza. As the Zionist leader Ze’ev Jabotinsky wrote in 1923, “Zionist colonization . . . can proceed and develop only under the protection of a power that is independent of the native population [i.e., Palestinians] — behind an iron wall, which the native population cannot breach.”

Of course, in 1923, as students see in the mixer, the “power that is independent of the native population” is the British Empire. The abolition of Palestine and the creation of Israel is impossible to imagine without the iron wall of empire. And, speaking of empire, it is worth remembering the essential support for the Balfour Declaration of Woodrow Wilson, another individual in the mixer. As Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote, Wilson’s support “made possible” the Balfour Declaration. Rashid Khalidi summarizes: “Throughout the intervening century, the great powers have repeatedly tried to act in spite of the Palestinians, ignoring them, talking for them or over their heads, or pretending that they did not exist.”

There are lots of moving parts in the “Seeds of Violence” mixer, and inevitably students will remember different facts and draw different conclusions. For me, the important thing is that they grasp that to explain what is going on today, they need to know something of what went on more than 100 years ago. History matters.

Today’s violence did not begin on Oct 7. It did not begin in 1967. It did not begin with partition and the Palestinians’ Nakba — Israel’s “war for independence” — in 1947 and 1948. It did not begin with the Holocaust. No. It began with the Zionist movement’s conviction that Palestine should be a Jewish-only country and that Palestinians should disappear.

Sample Roles

Najib Nassar

Palestinian newspaper publisher

I am editor-in-chief and publisher of the biweekly newspaper al-Karmil, which began in Haifa, Palestine, in 1908, in what was then the Ottoman Empire. We didn’t have a huge circulation, but nonetheless tens of thousands of Palestinians either read or “heard” my newspaper. As I wrote: “Once I went to one of the Palestinian towns in which there was only one subscriber. Many received me with honor as the owner of al-Karmil, which I had not expected and found strange, until I learned that more than 50 persons from that town read the newspaper at the subscriber’s [house].” Of course, many Palestinians could not read or write, but they would go to one another’s homes and someone would read the paper aloud.

My newspaper led the campaign to prevent the Ottoman government from selling land to the Zionists. The Jewish National Fund had been founded by the Zionist Congress, held in Basel, Switzerland, in 1901, to purchase land in Palestine to support the creation of a Jewish state — the Jewish National Fund saw itself as the “Jewish People’s trustee of the land,” acquiring and developing more and more land. In 1910, a wealthy absentee Beirut landlord, Elias Sursuq, agreed to sell a huge parcel of land to the Zionists. But this was unfair! Sursuq “owned” this land only because he took advantage of an old Ottoman Empire law to trick the Palestinian peasants out of what rightfully belonged to them. Sursuq only wanted money. The peasants wanted to keep their homes and their land; they resisted, and they were supported by Shukri al-‘Asali, the governor of the Nazareth region.

When the Zionists came to our country, they did not care about us Palestinians — they wanted nothing to do with us. They set up their own banking system, their own stores, their own postal system; they even had their own militia. In fact, the Zionists wanted their own Jewish-only country. But no, this was our country. My newspaper wrote many, many articles about what was happening. Some Arab people did not see what the Zionists were doing. So I published a series of articles taken directly from the Zionists’ own writing in the Jewish Encyclopedia. I translated this into Arabic. When they write to each other, the Zionists are very open about what they are doing: They want Palestine to be a Jewish-only Zionist country. But Palestinian Arabs have lived here for centuries — Muslims, Christians, and Jews together.

Arthur Ruppin

Zionist Organization

Director, Palestine Office

Jaffa, Palestine

I moved from Germany to Palestine in 1907 and became director of the Palestine Office of the Zionist Organization in Jaffa. My job was to organize Jewish immigration to Palestine. I think I knew more about land in Palestine than anyone else. I helped direct what came to be called the Second Aliyah. Aliyah is Hebrew, meaning “rising up.” This “rising” was the great migration of Jews to Palestine, 1903 to 1914, when more than 35,000 Jews came to Palestine. Many Jews fled terrible violence throughout Europe, especially in Russia. In Palestine, I wanted to create what the great Zionist thinker Ahad Ha’am described as “a Jewish state and not merely a state of Jews.”

To have a Jewish country, everything depended on Zionists acquiring and developing huge amounts of land. As I wrote: “Land is the most necessary thing for our establishing roots in Palestine. Since there are hardly any more arable unsettled lands in Palestine, we are bound in each case of the purchase of land and its settlement to remove the [Palestinian] peasants who cultivated the land so far, both owners of the land and tenants.” When I arrived in Palestine, there were some Jewish communities from the First Aliyah migration where all the physical labor was done by Arabs — and Jews were the bosses. That was not the Zionist nation that I wanted to build. I supported what we called “conquest of labor,” that all the work in Zionist communities should be done by Jews and only Jews. So whenever my organization bought land, we would evict the previous tenants. Not because we hated the Arab Palestinians, but because we sought to build the Zionist ideal of an all-Jewish nation in Palestine. And for this, Jews and Arab Palestinians had to live separately.