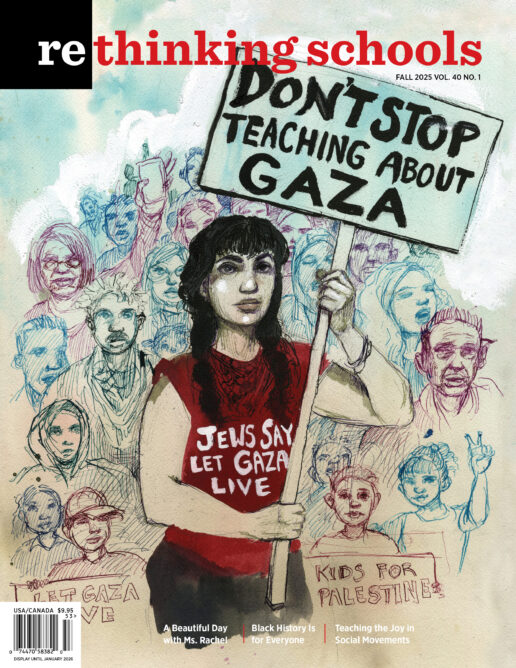

Families Talk About Palestine

A Liberatory Approach to Learning

Illustrator: Emily K.

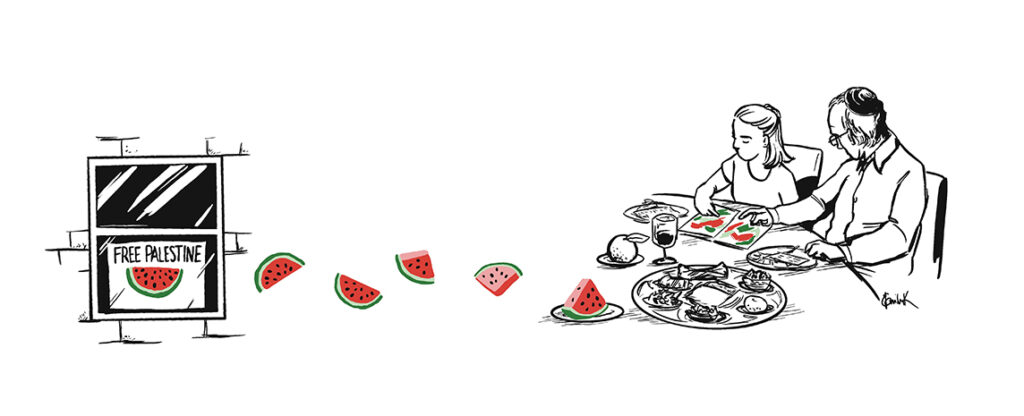

The sun filtered through the windows of our community hall as children of all ages held up their matzah. It was time for Yachatz — the part of the Passover seder where we break the middle matzah as a reminder that not everyone is free, that freedom is not yet whole.We spoke aloud about the people of Palestine, who are not yet free, and how this communal act could be both a reminder and a call to stand up for what is right. We counted: one, two, three — then sat in silence to listen to the crackle of the matzah breaking. The sound echoed through the room.

That moment, during our Family Freedom Seder, reminded me why we created the Liberatory Education Series in the first place: to carve out space for children and their caregivers to ask questions, learn together, and begin imagining a more just world, side by side.

The series was an intimate three-part journey held with a small group of families over several weeks. There were families who brought their 5th graders after they struggled with wearing their Palestine pins to school — confused why anyone could think that what’s happening in Palestine is defensible. There were families with toddlers who wanted to normalize liberatory education as part of their family’s values. And there were families involved in rallies and protests across the San Francisco Bay Area looking for a space to settle into discussion. The Family Freedom Seder opened the experience to a broader audience, inviting in dozens of new participants from across our networks. Together, they formed a powerful intergenerational community ready to reflect, learn, and act.

As Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP), alongside other organizers including Families for Ceasefire and Acorn Shabbat, we designed workshops that weren’t just for kids or just for adults but held everyone as participants. When one entered the small fireside room at a local Unitarian Universalist church, our families saw anchor charts across the room, some at kid-level and others at adult-level, asking them to consider big questions like “What makes you feel free?” and “Years ago the phrase ‘A land with no people for a people without a land’ was popularized when explaining the state of Israel. What does this intend to do? Why?” There were books splayed out across the coffee table with texts for more advanced readers like Questions to Ask Before Your Bat Mitzvah and Mahmoud Darwish’s The Butterfly’s Burden, and there were children’s books — many featured in Social Justice Books’ teaching Palestine work — such as Homeland: My Father Dreams of Palestine. Once everyone arrived, we’d sit around the coffee table — large blue couches arranged in a perfect U-formation. Toddlers sat on their parents’ laps, 5th graders sat on the ground, away from their parents but still a part of the community, and just like that, we’d begin each session with an opening circle. Our goal was to engage in truth-telling and political education with compassion and clarity — and to show that this kind of learning can begin at any age.

As a former classroom teacher, I know what young people and their families are capable of if given the platform and space. That belief led me to launch JVP-Bay Area Kids & Families, a project within JVP-Bay Area’s Education team aimed at mobilizing and building up our younger family community. Justice-based organizations like JVP must continue working toward creating meaningful organizing spaces for children and caregivers as crucial members of our movement. This series and seder were part of that vision.

Our goal was to engage in truth-telling and political education with compassion and clarity — and to show that this kind of learning can begin at any age.

An Overview of the Three-Part Liberatory Education Series

In Session 1: What Is Liberation? I wanted to create both a safe space for community members to share ideas, and to norm our understanding of different terms — and for younger folks to learn some new words. Members explored concepts of liberation in two different stations, set up on either side of the cozy fireside room. At one end, participants found Daniel Pennac’s The Rights of the Reader, stacks of lined paper, and pens. I invited participants to create their own list of “rights” that every learner should have access to.

One student’s list included the right “to ask questions,” “to make a mistake,” “to love who they want to,” and “to speak up if you think something is wrong.” The clarity and boldness of these rights grounded the room in what liberation could look like through a child’s eyes.

On the opposite end were images inspired by The Giving Tree, where the tree is slanted so one character can reach and gather far more apples than the character on the left. Participants analyzed the series that included an image of equality — both characters have the same size ladder to reach the apple tree. Equity — the character on the left has a larger ladder so they can better reach their side of the slanted apple tree. And lastly, justice — wooden aids put into place to support the tree in growing straight, so both characters could access the tree without additional aids. As one participant noted, “Instead of changing the people, they changed the tree!” In other words, true justice is the changing of systems. Participants then folded pieces of blank paper to make their own four-part image series to demonstrate inequality, equality, equity, and justice. Some pulled from their school experience, thinking about the use of different pencils, while some created stories including surfers catching varying waves based upon their surfboards.

Session 2: Palestine Past & Present invited families to engage with the history and present-day reality of Palestine through a multisensory and inquiry-based approach. At the center of the session was an accordion-folded flipbook of maps showing Palestinian land loss over time. I announced that we’d look at these maps in small groups, with myself leading the overall discussion. Families stuck together but merged with one or two other families to form small discussion groups. I guided all groups to slowly open individual sections of their accordion books, looking at each time stamp individually to hold the weight of change over time. Using developmentally appropriate questions — What do you notice? What do you wonder? — participants shared their initial noticings at each stop along the flipbook. “There’s so much less Palestinian land,” a 3rd grader shared as we compared 1917 to 1946.

I slowly pushed us further along at each “stop” in the map series. At the 1948 map, after an initial “notice and wonder,” I asked, “What do you think it was like for Palestinian people who lived on Palestinian land — and whose parents, and parents’ parents, lived on that land, that became labeled Israeli land in 1948?” Giving families a couple of minutes to discuss, I followed up: “What do you think happened to those people? Do you think they stayed there? Do you think they were pushed out?”

The beauty of this program was families could go as deep and as detailed as they wanted to, knowing their own children best and how to meet them where they are amid these harder conversations. I merely provided the framing, the resources, and held the container for them to engage with the content. Some parents chimed in with their small groups naming, “A lot of people were pushed out of their homes,” whereas others stayed centered in the feeling — tapping into empathy at the core of the map analysis. Once each page of the flipbook had been opened, I prompted one final comparison: “Look back at the 1917 map and then 100 years later in 2017. What do you think it might feel like if this was your home, and you looked at this map? What would you do about it?”

Although my love of teaching geography guided a larger section of this session, I wanted to ground the program with people, not merely maps and data points. Displayed across the bookcases was a gallery wall of photographs from Palestine past and present including children playing, women cooking, and mules walking across the hills, but also buildings destroyed after bombs had struck, land ravaged. There is joy, there is culture, there are real people — not merely a concept or an idea. Traditional Palestinian music played in the background, and we offered bites of Palestinian food. These images and sounds helped anchor what was otherwise a complex and painful topic into something tactile and real, offering space to reflect on what was, what is, and what could be. I wanted to bring in my own lesson structures from Black Lives Matter at School Week of Action, where we learn and discuss injustices, but we also uplift and celebrate people, culture, and joy too.

Session 3: How to Show Up invited families to explore what it means to actualize our hopes. My collaborator from Acorn Shabbat, who I met through our shared distaste with a local Jewish organization that remained silent amidst the genocide, offered to lead a short drum circle — she works as an East Bay street-drumming educator, not too different from D.C.’s Teach the Beat program — and practiced a chant that could be used in protest marching. From there, I distributed “Find Someone Who”-style bingo boards. Items across the board included “has been to a protest” and “wrote a letter to your local government,” but also “likes to sing or play a musical instrument,” “makes art,” and “tells or writes stories.” After several participants — of all ages — called out “BINGO!” I brought us back together.

“What might all these items on your “Get to Know You” board have in common?” “They’re all about the arts and protest!” one 2nd grader whispered to their parent. “Would you like me to share that with the whole group?” the parent politely whispered back. A silent nod, and we all got to hear their wonderful idea. “But what about ‘helps out in a school, home, or neighborhood garden?’” Families turned and talked to one another. “They’re all about making the world better,” another shouted. “Aha!” I shared with excitement. “Thumbs up if you’ve ever heard the word activist.”

After a heartfelt discussion of activism and ways we can show up and take action for what’s right, it was time to engage in activism of our own. I held up tools participants could use to teach others as just one way of being an activist. “Here are postcards if you want to write a letter to someone else, sharing with them something you learned over these last three weeks, here’s poster paper if you want to make a poster about it, comic strip if you want to tell a story, blank paper for pictures,” the list went on, plus additional brainstorming from our “Find Someone Who” board that included writing a song, creating a dance — anything! A 2nd grader, with support from her parent, wrote a story about Palestinian land loss from the perspective of an olive tree. She ran up to me every five minutes or so to share a new idea or element of the story, her excitement at her own creative juices was a sight to see. A pre-school student sat on her dad’s lap and drew a picture of a Palestinian flag, after a back-and-forth discussion about what she wanted her dad to write next to her drawing of the flag. A kindergartener approached her mom, asking, “How do you spell Palestinian?” and then wrote “This is Palestinian land” on a postcard she planned to write to a family member. This session was less about product and more about process, giving young people space to reflect and respond in ways that felt meaningful.

You don’t need to be an expert. You need a space, a few committed people, and a shared belief that families deserve to learn together — sometimes in tears, sometimes in laughter, sometimes with crayons and grape juice on the table.

The Family Freedom Seder

The culmination of the series brought everything together. Rooted in the structure of a traditional Passover seder, our Family Freedom Seder was reimagined for our intergenerational, justice-centered gathering. We invited participants to imagine new items they might place on their seder table this year — symbols that spoke to their values, questions, and hopes. Toward the beginning of the evening, a 6-year-old stood before a room of about 60 participants. They would place an apple on the table to represent anger — “because sometimes we feel angry,” they explained, “and that’s OK.”

“Now hold up your maror — your bitter herb. Close your eyes and pretend you’re eating the bitterest, grossest thing. Now open your eyes and show your bitter face to someone next to you.” Giggles echoed across the room. “Why do you think we’re about to eat something bitter?” “To remember the bad!” a kiddo shouted out. “That’s right!” I yelled, trying to keep momentum with my teacher voice. “Now close your eyes and picture the sweetest thing you’ve ever eaten. Your most favorite food. Open your eyes and show your ‘Mmm, I just ate something sweet’ face to someone near you. Share what you were picturing.” After a pause for folks to share with one another, I projected again: “We dip the maror — the bitter herb — in the charoset, the yummy sweetness. Why do you think we do that?” One young participant reflected that “It’s just like life, sometimes bitter and sometimes sweet.” Similar in ways to my leading of the Palestine Past & Present session, I wanted to be sure we considered sorrow and joy at the same time. There’s the bitterness experienced by those who were enslaved — and those who continue to be — mixed with the sweetness of celebration for those who are now free, and a joy, or perhaps sense of hope, in our collective resistance.

Reflections and Replication

This series was a beautiful, challenging, and imperfect beginning. One of our biggest struggles was capacity. Curriculum planning and facilitation fell on a small team of committed folks including a music teacher, a pediatric speech-language pathologist, a rabbi, and a few passionate organizers, while many volunteers stepped in only for day-of logistics. Moving forward, we hope to grow a stronger collective of educators, caregivers, and youth to share in the dreaming and the doing.

If you’re reading this and wondering if you could do something similar in your community: The answer is yes. You don’t need to be an expert. You need a space, a few committed people, and a shared belief that families deserve to learn together. That children can handle big truths. And that liberation is something we build with our whole selves — sometimes in tears, sometimes in laughter, sometimes with crayons and grape juice on the table.

Ultimately, what we created through this series and seder was a space for families to begin learning not just about liberation, but in liberation. A space to make meaning of Yachatz — the dividing of the matzah, and the dividing of our world — and to imagine how we might move toward wholeness. Toward justice for all.