Embracing Asylum-Seeking Students and Their Families

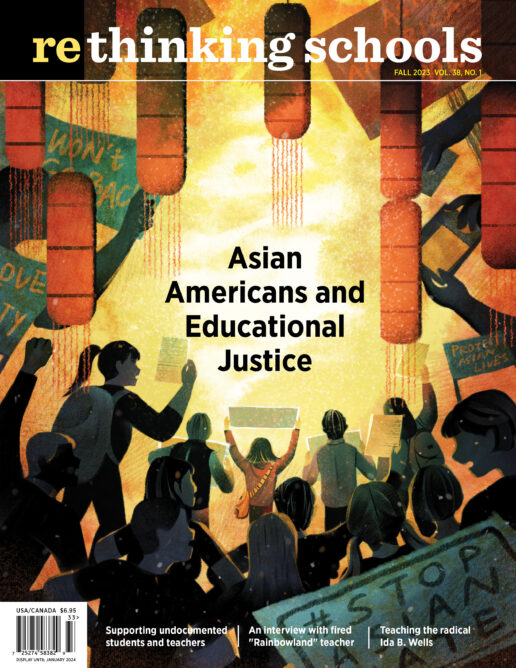

Illustrator: Adolfo Valle

Home visits are a foundational practice of my labor as a community teacher. However, this year they were completely different.

This year all of the families of the 15 students in my 4th- and 5th-grade transitional bilingual classroom had left their homes and traveled thousands of miles through the Darién Gap (a treacherous 60-mile stretch of jungle between Colombia and Panama), Central America, and Mexico. They had met border patrols in Texas and been trafficked as political pawns by Texas Gov. Greg Abbott via bus to New York City. It was infuriating to see the power and dysfunction of our political system over students’ and families’ lives. Media coverage of “busing migrants” is now seemingly routine with more than 34,000 individuals having been moved across the country as a political stunt. Where are the stories of individuals and families? Who are the “migrants”? Where are they from? What were their lives like before? What hopes and dreams do they have?

Social justice educators often talk about “grounding our curriculum in our students’ lives.” It can sound easy and straightforward. But it never is. And this year, especially given the challenges of working with young people who continue to go through such trauma and turmoil, my efforts to learn about my students, their families, and their “homes” challenged me to be more imaginative and adaptive than any time in my career.

When I learned that I would become the transitional bilingual teacher for a group of 4th- and 5th-grade students who had recently arrived in New York, I felt excited, anxious, and worried about how to welcome kids and families after such harrowing journeys. I was determined to find better ways of learning and welcoming than my parents and I encountered on my first day of 5th grade.

Though I had the privilege of arriving with a green card, I had also migrated to the United States from Latin America. My mother brought my brother and me to New York from Ecuador in the search for a mejor futuro [a better future]. I remember my cousins asking if I wanted to go, if I was going to miss my grandparents, and when I was going to come back. I didn’t know how to answer. It was decided for me that I was leaving my family and what I knew as my home. I had to leave my grandfather parting my hair and combing it before I walked down to school, the soccer matches with my friends after school, the freshly baked bread from stores for afternoon coffee, and most of all my aunts and cousins to care for me. We arrived on a spring night at JFK, the humidity and the smells of the city overwhelming — uncomfortable, stuffy, loud, strange. Although I heard the joy in family that welcomed me, I felt lost.

I wondered what my new students felt, what they thought. I felt an urgent need to know my students, their families, and their stories. As I welcomed them into the classroom, I decided to lean into my practice of home visits even more.

But I realized I needed to change the way I did home visits, even the language I used to describe them. I chose the phrase “family connection” because the idea of visiting students’ homes didn’t seem to fit. They were just becoming acquainted with their hotel rooms, the stale meals, the noisy and dirty sidewalks, the rush of Manhattan. This was new, uncertain, and it felt unfair to ask for them to propose a space to call home. Meanwhile, family is what they still had, what kept them going in their journey, and what they believed in and could trust.

I also realized I needed to change the meeting place and the process of setting up visits. My students’ families were making a home in the hotel room they had been assigned. So this year I offered to meet families at the shelter, a park nearby, or at school. Their emergency shelter was located in a hotel in the center of the bustle of Manhattan, a few blocks from Times Square, which my kids named las pantallas [the screens]. At the shelter there were safety officers with a strict check-in/check-out system, and a case worker from Social Services.

I sent a welcome letter home with my phone number and reached out to families when they picked up their kids from school, asking if we could find a time and place for una conexión familiar [a family connection]. Given most didn’t have cell phones or emails, and many were juggling looking for work, scheduling doctors’ visits, and navigating immigration appointments and locations for all, I tried to keep the request and the options as straightforward as possible.

As I prepared to meet families, I reflected on how my students’ stories might resemble my own. When my mother and I arrived on my first day of 5th grade, she spotted Pedro Rodriguez and asked “¿Habla español?” [“Do you speak Spanish?”]. He nodded and then she asked him to take care of me for the day. When she left, the look on his face was as lost as mine. Everyone was moving so quickly, there were hundreds of kids and so many words I didn’t understand. Pedro led me to our teacher, Mrs. Cohen, who taught in English the whole day. I was lost, embarrassed, and desperate to go back to Cuenca with my grandparents, aunts, and cousins; I wanted out! I was handed from one person to the next in a sea of English and hand signals and stares. I knew I didn’t want this experience for my students. I was determined to ensure they felt seen, felt whole, felt that they mattered, and that they had a choice.

I made a plan to begin each family visit by sharing my own journey as an immigrant and my values of respect, collaboration, responsibility, and love for my family — all of which help me establish a community of care and support both inside and outside the classroom. Communicating these values to families helps me team with parents to support our kids. I gently ask for parents’ trust as I begin the journey of teaching and learning with their children. I asked parents and kids to share what they wanted for a year of learning and then transitioned our conversation to their journeys by asking “¿Quiere contarme un poquito de su viaje, de su travesía?” [“Do you want to tell me a little about your journey, about your crossing?”] This question was an invitation for desahogo [relief, venting, resting] space for families. Giving families an opportunity to tell about their journey without judgment or interruption seemed to build trust and understanding. My invitation was often followed by a sigh, or deep breath, a change in expression, and a story.

* * *

One Saturday I had five home visits at the shelter. In a corner of the eating area, I set up a table and chairs to meet with families amongst the noise of other residents lining up for breakfast and lunch.

Ivan sat down with his mom, younger sister, and father; they had migrated from Colombia. I shared a little about my own arrival at Ivan’s age, though unlike him I didn’t have to sleep in the desert and endure treatment by ICE agents. Then I asked about their travesía [crossing journey]. Ivan’s mom Pamela took a deep breath and shared her family’s story of being forced to leave their home. She had been successful as an entrepreneur, and the local gangs noticed and ruined her business — twice. The trip was planned over several months, saving money, selling goods, and saying goodbyes. They all shared how harsh it was for them when they arrived at the Texas border. Ivan talked about the cold he felt sleeping in the desert. They walked for days. She eventually decided that they would hand themselves to the border patrol and called them with the cell phone she carried. I asked Pamela about the dreams and hopes she had for Ivan. “Yo quiero que el aproveche y que aprenda, que haga lo mejor por superarse.” [“I want him to take advantage of the opportunity to learn, and do his best to get ahead.”] I walked away from our visit with a deep desire to create space for students’ lives and their journeys in my lessons.

On another visit at the schoolyard, I met with David, the dad of my students William (4th grade) and Wendy (5th grade). My principal joined me on this visit; this was the first time a principal had accepted an invitation in my open calendar of family engagement events. After sharing a little about my journey to New York when I was Wendy’s age, I asked my students to share a bit about themselves and what they enjoyed in school. William said, “A mí me gusta estar en la clase y aprender con mis compañeros.” [“I like to be in class and learn with my classmates.”] When I asked David to share about himself, including their crossing journey, he brought out his phone and thumbed through pictures, eager to share with my principal: “Mire. Aquí estamos en la selva, con otras familias.” [“Look. Here we are in the jungle, with other families.”] He added with a glowing smile, “Mire. Todos juntos, en familia todo el camino, siempre juntos.” [“Look. All together, together as a family the whole way, always together.”] The images showed several people walking in mud, looking tired as they sat or walked in the jungle. I asked my principal if she had questions for him. “What can we do for you and your family?” she asked. “What do you want that we might be able to provide besides school?” David shared, “Yo estoy buscando trabajo, profesor, nosotros venimos no a ser una carga para nadie, venimos a trabajar y ganarnos nuestro puesto aquí.” [“I am looking for work, teacher, we are not here to be a burden to anyone, we are here to work and earn our place here.”] I translated for my principal and then we sat without a satisfying response; we promised to ask around.

* * *

As the school year went on, my class of 15 gradually settled into the routines of learning. We had morning meetings to check in on our emotions and happenings, which evolved from greetings to sharing about feelings to a circle of gratitudes and affirmations. I read Pam Muñoz Ryan’s Esperanza Rising (Esperanza renace) aloud, as a way to bridge curriculum to students’ recent experiences. Set in 1930s Mexico and Southern California, Esperanza, the 13-year-old daughter of a wealthy ranch owner, and her mom reluctantly decide to escape Aguascalientes after her father’s death. Their journey of crossing the border undocumented and then re-establishing their lives from poverty seems to provide deep connections for many of my students.

Although Esperanza’s story is from a different cultural background and in a different time period, it shares a number of details that were validating to my students. Esperanza and her mother are forced to leave Mexico and arrive in California with nothing. She has to remake her identity, learn English, and establish a new family, while still missing her grandmother on the other side of the border. Esperanza’s trip was also treacherous, as she escaped hiding in between the floorboards of the carriage to make it to a tight, hot, and dusty train ride to the U.S. border. Students drew emotional timelines of Esperanza’s journey. We shared how we could sympathize with Esperanza, Miguel, and missing abuelita [grandma]. Students pleaded, “Ay, profe, nos lee un poquito mas, por favor” [“Oh, teacher, read us a little more, please”] as I closed the book for the day.

* * *

We celebrated the winter holidays with pizza and presents from community members. When we returned from our break, I learned that I would receive an additional 17 Spanish-speaking asylum seekers from Latin America and that I would now be teaching transitional bilingual 3rd, 4th, and 5th grades. They gradually arrived two to three at a time in the first two weeks of January. My students cheered at first with more friends and eventually they felt the tightness in our classroom. Our routines were disrupted and the relationships they had developed with each other had to be remolded. This was a challenging time. Each group created table group agreements, we revised our community agreement, and played name games to meet each other.

Eventually I decided to weave this new dynamic of my growing classroom community into my curriculum. During a writing unit I created, students learned about each other via interviews and wrote a short news story about their classmates. I carefully arranged pairs of established and new students and they asked each other: ¿De donde vienes? [Where are you from?] ¿Quién es alguien importante en tu vida? [Who is an important person in your life?] ¿Qué es lo más difícil que has hecho? [What is the hardest thing you have ever done?] ¿Cuál fue un momento feliz en tu vida? [What was a happy moment in your life?]

As I walked around I heard heartwarming conversations about birthday parties and learning how to ride a bicycle. There were stories of missing Venezuela and trips through the jungle: “Yo me demoré 13 dias.” [It took me 13 days.] “Era difícil dormir en la noche con todos los ruidos en la selva.” [“It was hard to sleep at night with all the noise in the jungle.”] Students listened to each other and provided kid-comfort; they seemed to understand each other in a special way. This unit created space for students to share the stories of their journeys and their lives before being brought across borders.

* * *

My family connection visits also changed with this new group of students. Listening to kids share in the classroom helped me see how rich their lives were before they became “migrants.” I still asked parents broadly about their experiences but now I also focused on what their kids did before arriving. I also left more time for parents to tell stories, and I invited my students to share their dreams for the school year. I tried to be open to listening to whatever they wanted to share, regardless of the topic.

One afternoon I sat at the round table in my classroom with my students Mario (3rd grade) and Elena (5th grade), and their mom and dad Yadira and Gregorio. I started by welcoming them and making time to join me in sharing about me and learning about them, and then I said, “Quiero aprender un poquito de cada uno de ustedes. ¿Qué es algo importante que quieren que yo sepa?” [“I want to learn a little from each of you. What is something important that you want me to know?”] Yadira shared how difficult it had been to arrive in New York City, crossing through the jungle. She was hopeful for her kids’ future, and desperately wanted them to learn English and do well. She also shared her fears of Elena going to 6th grade. Tears followed her hopes and worries. Elena shared how much she missed her family in Ecuador. Then she shared her dream to grow up to be a professional dancer. She cried right after, remembering her ballet school in Ecuador. What a stark contrast to the media images of kids in aluminum blankets at the border and families running with only their clothes and a bag. Elena had a beaming life before crossing the jungle.

* * *

Every year, home visits gift me moments that shape my year of teaching and learning. I listen closely and carry the stories with me to guide me in selecting read-alouds, writing prompts, and especially for ways to bridge to and ground curriculum in students’ lives — to make learning real and relevant for my students and their families. I was awed by how raw and recent hardship and courage seemed to birth enthusiastic and curious learners. Our class charter “Nuestro Acuerdo” now includes the concept of listening to each other and holding space with compassion.

This year I had the humble honor to teach in Spanish, my first language. And, it has been a tremendous challenge to show up every day to teach and translate and interpret language and culture to my students and their families. Simultaneously responding to and making connections for the English-speaking adults that surround us brought innumerable misunderstandings and missed connections. Teaching in a classroom designated “transitional bilingual” meant that the program’s ultimate goal was to bridge to English. But for me, it was so much more than just teaching English. It was protecting my students’ and their families’ cultural wealth and well-being. It was a year of centering our Latin American roots, language, ways of being, foods, stories, families, immigrant journeys, and dreams. Grounding the curriculum in students’ language and culture gave us a shared foundation for talking about other topics — history of the United States, Indigenous people, African American history, math, social and emotional health, etc.

As some students and their families move to other communities and move on to English-only classrooms, I hope their teachers will center their humanity, protect and honor their home languages, and continue to establish relationships and build community. As a community learning together we can grow to heal each other.