Preview of Article:

El corazón de la escuela/The Heart of the School

The importance of bilingual school libraries

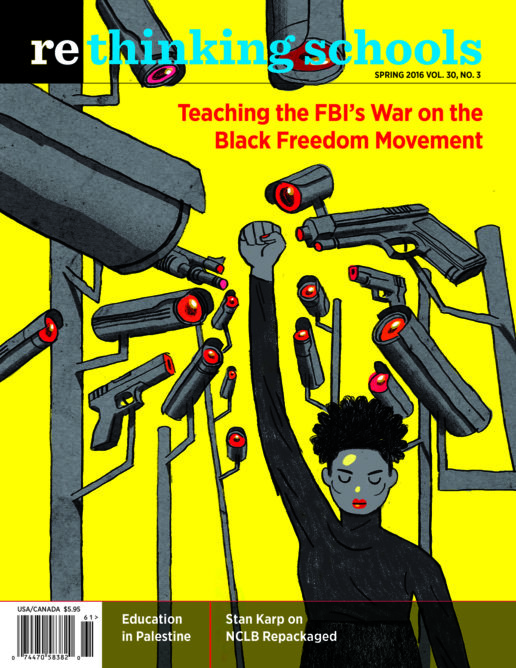

Illustrator: Simone Shin

A 30-foot-long grey whale skeleton visited my school library for a week last spring. The whale arrived in many parts—giant vertebrae piled up in bins and boxes; long, curved ribs carefully carried up the stairs and down the hallway; the enormous and beautiful white skull pushed slowly on a wheeled cart from Mission Science Workshop, based in the neighborhood a few blocks away. As the teacher-librarian at a bilingual elementary school in San Francisco, I worked on coordinating Whale Week for more than a year. Now it was upon us, and I was grinning from ear to ear as I watched the children’s mouths drop open at the sight of the huge collection of bones moving into our library.

Our students spent a month studying grey whales, which migrate each year along the California coast between Alaska and Mexico. It was an engaging schoolwide topic, especially because most of the children’s families themselves migrated from Mexico and Central America. During Whale Week, each class spent an hour in our school library learning from the Mission Science Workshop staff, in English and Spanish, about whales. Each class worked together to assemble (and then disassemble) the grey whale skeleton, piece by piece, nestling numbered vertebrae together like a giant puzzle and tying ribs taller than 5th graders to a specially constructed wooden frame. Flippers—with finger bones clearly visible—fanned out from the whale’s giant shoulder blades. The fully assembled skeleton spanned the entire length of our library.

Throughout the week, parents and community members stopped in to help with the bones and marvel. Several classes of 6th, 7th, and 8th graders from the middle school next door also visited. They helped our preschool and kinder students lift and place pieces of the skeleton. On display around the library were myriad books about whales and other ocean animals. The whale website I created with photos and digital resources was up on the computer screens. Recordings of whale sounds emanated from computer speakers while the children worked to match together almost 200 sun-bleached bones.

This powerful, bilingual, integrated learning experience in our school library was a collaboration between many players: a community organization dedicated to bringing hands-on science to low-income Spanish-speaking youth in the Mission District, our school’s science resource teacher, our gardening intern, classroom teachers, and me—the teacher-librarian. Funded through a modest library budget, our school’s Whale Week is an example of the kind of creative, literacy-rich, and intercurricular learning opportunities possible with a robust school library program. It is one of many reasons we need our school libraries and teacher-librarian positions to be adequately funded.

In recent years and across the nation, school library programming has gone the way of art, music, PE, and other “supplemental” or “special” programs in public schools. Nowhere has this reduced funding for libraries had a more devastating impact than in California, where we currently have one credentialed school librarian for every 7,187 students, according to the state’s department of education. The California School Librarian Association (CSLA) drives home this shameful fact by pointing out that Texas—the state with the next largest population of students—has approximately one teacher-librarian for every 1,080 students; Mississippi can boast roughly a 1:575 ratio. California is at the very bottom of this absurd range of statistics. Each time I attend the annual CSLA conference, it is noticeably and sadly under-attended.