Education and Social Justice: A Global View

An Interview with Angelo Gavrielatos

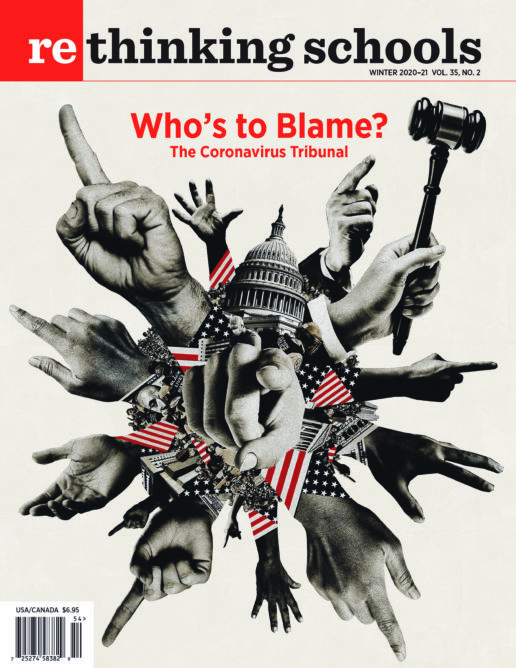

Illustrator: Keith Henry Brown

Angelo Gavrielatos is the president of the New South Wales Teachers Union. Previously he was the federal president of the national Australian Education Union, and he worked five years for Education International, leading EI’s response to privatization and commercialization of public schools. He was interviewed on Feb. 8, 2020, by Bob Peterson.

How did you originally become a teacher union leader?

The answer goes back to why I became a teacher. Like many others, I was inspired by my own teachers. I grew up politicized because of my family background and was active politically at university. Early on I recognized that public education is a great social enterprise that has the transformative power to create a better society. It led me to joining my union on my very first day of teaching.

Once a teacher, I realized that if you want to make change in your classroom alone, that’s great, but if you want to make change beyond your classroom or school, the only way to do that is through the collective strength of our unions.

What pushed you to believe teacher unions should go beyond narrow trade union demands and take up social justice issues?

I was never attracted by narrow economistic unionism. We are privileged in the teacher union space to be able to go easily beyond narrow unionism. In some other unions and industries, making that connection with social justice issues is more difficult. I was always drawn to an appreciation of the broader role of education and unionism in building community and movements. I realized the power of the collective in transforming schools and society. My perspective was further influenced by writings about social justice unionism in Rethinking Schools many years ago. I am referring to the taxonomy that distinguishes between economistic unionism and social justice unionism. There was one other publication of yours, Rethinking Globalization, that sticks with me. In that, a high school student was . . . quoted saying something like “once you’ve tasted the thrill of solidarity, there is no way of going back to individualism.” I use that statement in mass rallies with young teachers all the time.

What is Education International?

Education International (EI) is a global federation of teacher unions and other education employees. Together it represents more than 32 million members from 179 countries and territories. Among other things, EI promotes the “principle that quality education, funded publicly, should be available to every student in every country.”

What was your role in EI?

Previous to me working for EI I was connected with its leadership while serving as president of the Australian Education Union. In 2012–2013 we realized that we had become very good at describing the problem of privatization and commercialization of our schools and that we gave great speeches, but what we hadn’t done was figure out what we were going to do about it. In 2015 I stepped down from being AEU president, moved to Brussels, and became responsible for leading EI’s global campaign against the growing threat of commercialization and privatization of education.

At that time, large global corporate actors had already started using their huge reach, depth, and strength to target public schools with no regard for national borders. These forces are capable of exerting incredible influence across the globe. They are stronger than most governments in the countries in which they are operating. EI decided enough with describing the problem — if we are going to confront it, we needed to start building a genuine global response to deal with the global dimension of privatization.

Who are some of the key players that you are referring to?

Pearson is the biggest global actor, and it has changed dramatically as a company. What started off as a publisher some decades ago has now made a conscious decision to move almost entirely into the digital space and is seeking to expand its reach over public education. It’s pretty much a tech company now, and it [and] a few other tech groups are driving this privatization agenda.

It’s not only the corporate world. We also have this agenda being driven by the World Bank and other related international financing institutions and intergovernmental organizations. They are doing it all for ideological and financial reasons. Education is valued around $6.3 trillion (U.S.) a year. It’s a “very lucrative market,” as they would describe it, but to get to that market, education has to be removed from the public sector. Some five or six years ago there was a meeting of venture capitalists in the U.S., and they declared they were satisfied with the extent to which they had privatized health care, and their new frontier was education. Education is not only a lucrative market for these groups, but it is the most sustainable market in the world.

How many countries did you visit in your five years as leader of the anti-privatization campaign at EI?

I don’t know. I’ve lost count — many countries, maybe 40 or 50, but I actively worked with a smaller number. In each country there are various manifestations of privatization — depending on historical and political factors. But every country was somewhere on a continuum of levels and types of privatization.

What’s an example of a privatization attempt?

Liberia. In 2016 the Liberian government announced its intention to outsource all of its primary and pre-primary schools to one global actor called Bridge International Academies supported by the likes of Pearson, the World Bank, Zuckerberg, Gates, and others.

That is the endgame. The moment when a government hands over all of its education system to a corporate entity. People have said to me, “Liberia is an outlier. Is that the best example you got?” Interestingly, at same time in February 2016 that the Liberian government was announcing its intention to outsource all of its schools to private actors, David Cameron, England’s prime minister, announced an almost identical policy stating his intention that all schools that remained in control by local government authorities become academies operated by private actors. Academies are analogous to privately operated charter schools in the United States. So it’s not just Liberia but countries like England. I dare say that’s the intention of the Trump administration — to see all schools in the hands of private actors, destroying that social enterprise of free, quality, secular, universally accessible public education for all.

What’s the status of the anti-privatization fight-backs?

There are lots of fight-backs underway. It’s important for teacher union leaders to recognize that the biggest and maybe the last barrier capable of stopping these privatizers’ dreams is the teacher union movement — domestically and internationally. There are other organizations defending public education, but unions are the strongest and most capable of mounting a sustained, organized defense. That’s why we’ve become targets of the privatizers and governments as well.

When we launched our anti-privatization campaign in the Philippines, a union leader said to me, “Angelo, you realize that you are asking us to do something that could get us killed.” Taking on these corporate actors like Pearson and their partner in the Philippines, Ayala Corporation, led this union leader to say that to me.

Our colleagues in Colombia, who are very familiar with targeted killing of their leaders, also said taking up this anti-privatization struggle could get more of their people killed. “We are taking on vested interests,” one leader told me.

In Uganda, supporters of privatization fabricated allegations against our researcher in 2016, and he was arrested and detained.

We never used to hear about this in the education sector. We heard about it in other sectors of the labor movement when vested interests were being exposed in mining, fishing, and logging. Welcome to the modern world of education that is worth $6.3 trillion.

We are having some success. Is it at the magnitude we’d like? No, but ours is a long struggle.

Give me an example of a success.

I mentioned Liberia, where the government initially sought to outsource all the schools to one actor, Bridge International Academies. We forced them to retreat. We attacked their strategy, and they were forced to come up with a pilot plan involving a number of actors. We weren’t fooled; we knew what they’re all about. In education policy, whenever a reformer uses the word “pilot,” one should read it as “We will do you slowly.” It’s the politics of gradualism and attrition. We continue to fight in Liberia. In Uganda because of our efforts the high court deemed Bridge International an “illegal operator” that “set out to operate illegally” and the court called on them to be shut down.

There was a similar case in Kenya. So our efforts using a variety of political and legal and other organizing strategies have resulted in some wins. But it is a long struggle. We will persevere, we must persevere at all levels — whether at the local, regional, national, or the global level. It is one struggle.

What are key lessons you’ve learned?

We started the global campaign in 2015 and refined it periodically based on our ongoing evaluations. We quickly realized that strategic research was crucial for us to understand the dynamic in each country, which varied greatly. There are a large number of activist researchers, academics around the world who want to help unions. Our researchers examined the various manifestations of privatization. Based on those findings we built national campaigns to confront privatization. A national campaign with a powerful inside-outside communication strategy is necessary. The inside communication was necessary to organize and mobilize our own members. The outside strategy was to inform and build the necessary alliances with other unions and like-minded organizations.

Building unity was also critical. Regrettably, in many countries around the world there are three, four, five, seven, or more teacher unions. In those countries unity is just a word. EI tries as much as possible to build solidarity — local, national, and global through action. Some of the solidarity actions were very powerful.

Give an example of one such action.

On a couple of occasions we linked the United States and U.K. unions with African teacher unions in actions against Pearson and the World Bank. We had leaders from a number of countries descend on Pearson’s annual shareholder meeting. We got inside and it was pretty powerful for a leader of the Kenyan teacher union and a Ugandan teacher union leader to ask them, “Can you explain to me why you think it’s a good idea what you are doing to my country? When did you ask us?” These were powerful moments, and the media and social media coverage in different countries helped spread our message.

Let’s change the conversation and bring it to the United States. What are your thoughts on the red state revolts of 2018 and subsequent strikes by UTLA, the CTU, and others?

Teacher unionists from a distance are looking very closely and have been following these developments in the United States. It’s inspiring and motivating to see teacher unionists in these “right-to-work” states say “enough is enough,” and it’s inspiring to see them rise up articulating the needs and aspirations not only of themselves but more broadly the needs of their students and public education. Those struggles in the United States in the last few years have been well located within the frame of social justice unionism.

U.S. historian Howard Zinn once told me, “If teacher unions want to be strong and well supported, it’s essential that they not only be teacher unionists but teachers of unionism.” How important do you think it is for unions to encourage their members to teach about the working-class struggles and social justice movements?

People have asked me why these large corporate actors — the Mark Zuckerbergs, Bill Gateses, and the Rupert Murdochs of the world are so determined to privatize schools. Do they really need to become richer? That question relates to Zinn’s statement, because there is something more fundamental that the privatizers want to control — the curriculum. Everyone recognizes the power of curriculum, because any curriculum taught today will shape the society of tomorrow. Given that . . . it’s key that both teachers and students understand the struggles and value of unionism and other social movements.

This raises the related issue of the importance of member education. As union leaders we must always ask, “How can we better educate ourselves and our members?” One of my colleagues in Canada talks about the need for leaders to “reach within, reach out, and reach beyond.” We need to reach within to ensure the heart of the union operation is operating in a democratic and effective manner and that we are getting the best out of all union leaders, officials, and employees. We need to reach out to all the members to make sure that they are fully appreciative of the struggle ahead and to enlist the support and the expertise in our broader membership. We have large memberships of very smart people. Are we working hard enough to enlist their engagement, their activism, their expertise? And then are we reaching beyond to the broader community of unions and union members and others to strengthen our movement? We need to do all three things.

Howard Zinn is absolutely right. We not only need to be students of unionism but we must be teachers of unionism.

You are returning to Australia to work in New South Wales, where massive fires have consumed millions of acres and killed an estimated billion animals. What advice do you have for teacher unions on the matter of climate justice?

We have the responsibility as teacher unionists to do four things, and I list them in no particular order: To look after our members, our schools and students, our communities, and our planet.

We are living in a climate emergency. What has occurred in Australia in the last couple of months [December 2019 and January 2020] has provided ample evidence for all those deniers. People ask, “Do you believe in the science?” What a ridiculous question. People might as well ask me if I believe there is a solar system or if the world is round.

The science tells us what’s happening. But like many other countries, in Australia the fossil fuel industry is corrupting the political process. There’s lots of work to be done. We need to fight that industry and their supporters. We need to ensure that we have the best curriculum available for teachers. We teach the science, we embrace science, we don’t teach dogma. The more we and our students understand the science, the better we can build the movement to confront the deniers.

In the U.S. and internationally, white supremacy and xenophobia are growing. How has the Australian teacher union responded to those issues?

The rise of xenophobia, the politics of fear, the politics of division — we are seeing that grow globally aided and abetted by the Trump administration; in Latin America with Bolsonaro and now in Bolivia after the coup; in Europe with Orbán in Hungary — it’s all around the world. In Australia we are not immune from these politics. Let’s not forget that modern Australia hasn’t reconciled its past with our First Nations people. For example, we still celebrate “Australia Day,” similar to your Columbus Day. Australia Day celebrates the Jan. 26, 1788, arrival of the Europeans to this continent, which was populated by more than 500 Indigenous groups. How can we seriously celebrate Australia Day when our First Nations brothers and sisters consider it to be invasion day? How is that a day of national unity? It’s a big debate. Conservative commentators attack anyone who dares question that holiday. A satirist said, “You’d think it’d be easy to get a consensus that committing genocide is a weird excuse for a barbecue.”

Of course, the politics of fear and xenophobia is not restricted to our Indigenous brothers and sisters; it also plays out through Islamophobia. Australia is not in a good place in terms of racism and xenophobia, and we will do everything, whatever we can, to develop the necessary racism awareness for our members and our students in order to confront and deal with racism. One of the things we say: “Racism stops with me.”

How has international solidarity between teacher unions been in recent times?

The leadership of the NEA and AFT is active on the international stage and we know that we can rely on the NEA and AFT to extend support to struggles involving sister unions around the world. That needs to be acknowledged. Regrettably, that is not apparent to everyone, but from my experience, I know the broader movement is grateful. And similarly, the broader union movement has lent support to our brothers and sisters in the United States.

During the height of the Red for Ed strikes in the spring of 2018, a lot of unions from around the world extended messages of solidarity to the U.S. At the height of detention of families and children at the U.S.-Mexican border when the U.S. government were putting children in cages, a lot of the unions around the world that had in the past been recipients of solidarity messages from the United States reciprocated, not as an act of reciprocity, but because it was an important statement to make. The challenge for all of us is to grow international solidarity at all levels of our unions. We need to reach within, reach out, and beyond on this issue as well.

How do we enhance notions of international solidarity among our members?

First, we acknowledge that our members are busy and stretched. Their work is ever increasing with the top-down compliance measures. I understand when our members say, “I haven’t got time to do more.” It’s through no lack of desire on the part of teachers to be informed and get involved. Teachers know that when it comes to the well-being of children, our concern goes beyond our classroom, our school, our borders — it’s global.

We should encourage the notion of solidarity that the well-being of any child anywhere in the world is teachers’ business.

How do notions of building solidarity intersect with the ongoing wars and massive refugee crises that exist in several places around the world? It’s easy to have divergent views on unions taking up those issues.

Promoting peace is teacher union work. Not long after WWII, dozens of countries formed the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Australian teacher union leaders came back from one of UNESCO’s early conferences with a message that has remained part of the DNA of our union ever since. That message was: Every war that is fought, is fought against children — it denies their hopes and dreams. That’s why peace and the antiwar movement is teacher union business. How many times have we in the teacher union movement been told “It’s not teacher union business”? We’ve been asked, “Why are you involved in the peace movement and antiwar movement?”

It’s because every war is fought against children. I think of war memorials that have stone panels engraved with names of those who died in war. Often such panels have blank spaces waiting for future names. Well, those panels will be engraved with the names of our future students, to say nothing of the thousands of civilians, many of them children who will forever remain nameless. If anyone says it’s not our business, then whose business is it?

Support independent, progressive media and subscribe to Rethinking Schools at www.rethinkingschools.org/subscribe