Editorial: Defending Immigrant Students — in the Streets and in Our Classrooms

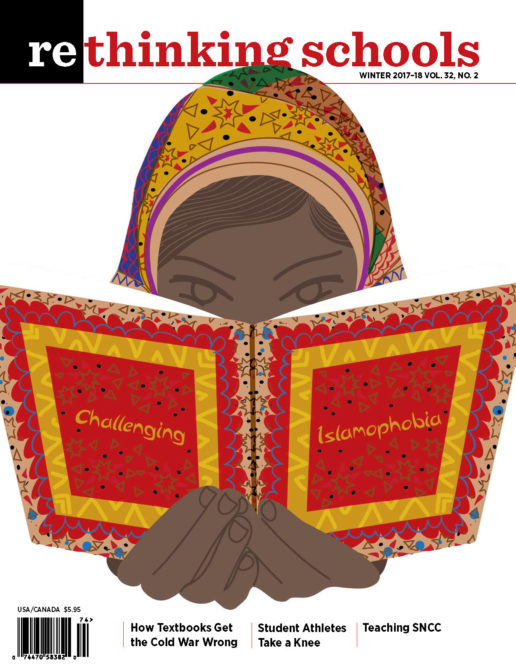

Illustrator: Favianna Rodriguez

In a recent New York Times opinion piece, “‘Dreamers’ Put Their Trust in DACA.What Now?” journalist Jose Antonio Vargas recounts the story of the first adult he ever told that he was in the United States without papers — Mrs. Denny, his high school choir teacher:

After she announced to our class that we were going to Japan for spring break, I pulled her aside and said that I couldn’t go. “I don’t have the right passport,” I said. Confused, Mrs. Denny replied: “Oh, it’s OK, Jose. We’ll get you the right passport.” I told her it was more complicated than that, that I didn’t have any piece of legal document that I could show, that I wasn’t supposed to be here. Her eyes widened, her lips pursed, and she didn’t say another thing. A couple of days later, to my surprise, she told the class that we were going to Hawaii instead. Years later, she told me: “You were my kid. I wasn’t going to leave any of my kids behind.”

Vargas’ answer to the article’s headline question about who Dreamers can trust? Teachers — “the ones who see up close the injustice of life as an undocumented immigrant in this country.”

We need to live up to that trust. It has always been an educator’s responsibility to act in solidarity with vulnerable students. But with President Donald Trump’s September declaration that he will end DACA, the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, we are called on to be more audacious, more resolute, and more imaginative in our solidarity with the 800,000 undocumented young people who now face a frightening uncertainty about their future in the United States. Some of these individuals are our students, but some are our colleagues; the Houston Chronicle estimates that 20,000 teachers are covered by DACA. We need to stand with them, too.

And, of course, the hate and fear that Trump’s tirades — and policies — are sowing are not limited to the 800,000 Dreamers; Trump hurls his xenophobic bile at all immigrants and their communities. Whether it’s the high school student in upstate New York who was taken into custody hours before his senior prom, or the father in Los Angeles snatched immediately after dropping his 12-year-old daughter off at school, Trump’s deportation machine is destroying families and communities and making schools a site of struggle.

Following the September announcement on DACA, high school students demonstrated their opposition across the country. Hundreds poured out of their classrooms in protest in Denver, Albuquerque, Phoenix, Seattle, Berkeley, Huntington Beach, and other communities. Educators need to stand with our students, as a reported 80 percent of Berkeley High School teachers did when students, organized by the Berkeley High School Chicano Latino United Voices, linked arms, formed a human chain around the school, and chanted, “No ban, no wall, education for all!”

Now is a good time to ask ourselves: What would a school district look like that acts in solidarity with our immigrant students? What would a school look like? What would our curriculum look like?

Milwaukee is one of many school districts where students, teachers, community members, and progressive school board members — including Rethinking Schools editor Larry Miller and Rethinking Schools contributor Tony Bez — organized to pass a resolution to establish Milwaukee Public Schools as a “safe haven,” which will not “allow any individual or organization to enter a school site if the educational setting would be disrupted by that visit.” The resolution provides for strict limits on the access of ICE agents to Milwaukee schools and students in order to “provide for the emotional and physical safety of students and staff.” Other pieces of the resolution call for school district-sponsored “Know Your Rights” forums for students and family members, designated resource people for immigrant students in every school, and districtwide professional development on “pathways to citizenship, opportunities available for college and training, financial aid, rights, and opportunities for immigrant and refugee students.”

Our schools need to be fortresses of safety, warmth, and determination, effecting the protections and affirmative actions like those called for in the Milwaukee resolution. And we need to call on immigrant communities to teach us how we can support them — “Nothing about us without us,” in the spirit of the expression coined by disability rights activists in the 1990s.

We need to press school districts to initiate measures to support our immigrant students and their communities. But we needn’t wait for them to act. At a teacher-community forum on immigration rights in Philadelphia following Trump’s election, organized by the Caucus of Working Educators’ Immigration Justice Committee, a Mexican mother of a 4th grader told participants through an interpreter: “I don’t know what to say to her or what answers to give. I felt the support of [her] teachers, but also the rejection of other teachers — indifference and discrimination. But I feel that your care as teachers — as angels — who surround my daughter can outweigh the indifference and discrimination from others.”

In every way we can think of, we need to be those activist angels.

Part of our response needs to be curricular. Whether it is Hmong, Somali, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Chilean, Guatemalan, Congolese, Honduran, Iraqi, or Mexican immigrants, our students need to appreciate the deep complicity of the United States in disrupting the societies that have forced so many people to flee their homelands. In an excellent In These Times article, “Don’t Punish the Dreamers — Punish the Corporations Driving Forced Migration,” David Bacon offers an indictment of the economic policies that have carpet-bombed the Mexican countryside.

Bacon writes: “It’s impossible to understand the outrageous injustice of deporting the Dreamers without acknowledging the reasons why they live in the United States to begin with.”

According to World Bank figures, in just a few years, from 1992-94 — immediately preceding the 1994 implementation of NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement — to 1996-98, extreme rural poverty in Mexico rose from 35 percent to 55 percent. By 2010, 53 million Mexicans lived in poverty. NAFTA required the Mexican government to abandon price supports for Mexican farmers at the very moment Mexico was being flooded with cheap corn, subsidized through the U.S. farm bill. Between 1992 and 2008, U.S. corn exports to Mexico increased more than fivefold. In the sick, contradictory logic of “free trade,” in NAFTA’s first decade, the price Mexican farmers received for corn fell by 66 percent, as the price of corn tortillas jumped 279 percent.

In some commentary about the “innocence” of the DACA Dreamers — who, it is said, arrived in the United States through no “fault” of their own — lies an implied indictment of Dreamers’ parents. But as Bacon summarizes, Mexican “parents aren’t criminals any more than their children are. They chose survival over hunger, and sought to keep their families together and give them a future.” A similar defense can be made for parents in other lands where the United States overthrew elected governments, propped up dictators, bombed, and destroyed people’s livelihoods with cheap produce.

This critical context is not just for adults. Through role plays, simulations, first-person readings, poetry, short stories, imaginative writing, and more, we need to find ways to share it with our students. [See the Rethinking Schools book, The Line Between Us: Teaching the Border and Mexican Immigration, and articles like “Who’s Stealing Our Jobs — NAFTA and Xenophobia.”] Part of expressing solidarity with immigrant students and communities means helping young people recognize the conditions that led immigrants to migrate in the first place.

Creating curriculum that addresses these vital issues needn’t occur in isolation. In Portland, Oregon, teachers have been meeting to develop and try out curriculum through the auspices of the Portland Association of Teachers (NEA) and the Oregon Writing Project. A role play is easier to write when its outlines are discussed as a group, and its writing is distributed through a number of individual teachers. And results can be shared through the network of teaching social justice conferences that have sprouted throughout the country, among other venues.

Racist and repressive immigration policies have had deep roots and bipartisan backing in the United States for decades, including during the Obama administrations. But Trump’s campaign of hate, hysteria, and militarized enforcement have made his anti-immigrant policies a centerpiece of his administration’s efforts to consolidate a reactionary takeover of U.S. political and social institutions. They need to be resisted as fiercely as we resist his efforts to expand mass incarceration, defend police violence, and make war on the poor.

As Jose Antonio Vargas reminds us, teachers “are the ones who see up close the injustice of life as an undocumented immigrant in this country.” In our unions, in our communities, in our school districts, in our schools, and in our classrooms, we have opportunities to act on our insights and our commitments. There is no time to waste.