Connecting the Dots

The 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom this past summer produced some brilliant commentary about the legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. One of the sharpest of these was a short essay that Michelle Alexander, author of The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, posted to her Facebook page. We want to quote at length from this essay because we think that it holds valuable even essential lessons for those of us working to defend and improve public schools.

Alexander urges us to look at King’s trajectory following the march:

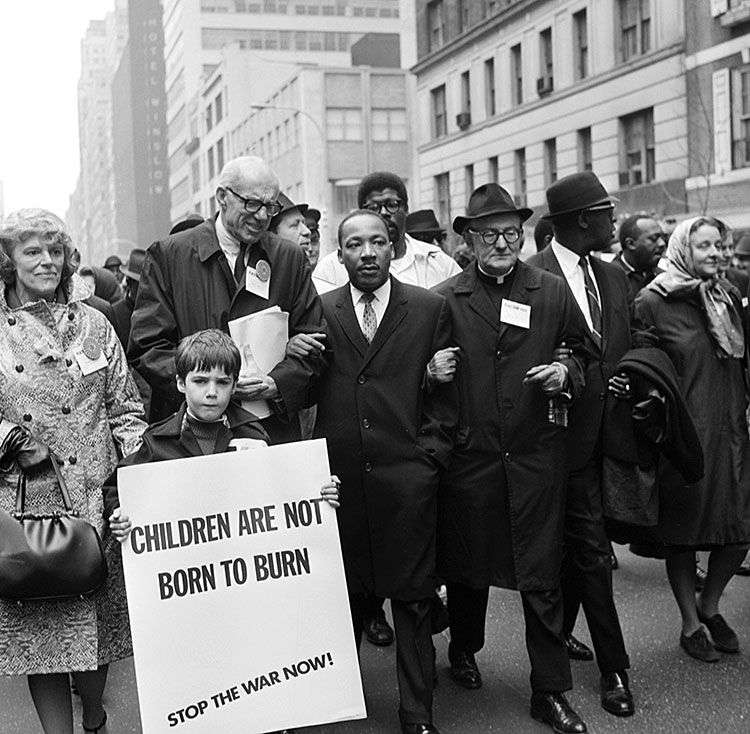

Five years after the march, Dr. King was speaking out against the Vietnam War, condemning America’s militarism and imperialism famously stating that our nation was the “greatest purveyor of violence in the world.” He saw the connections between the wars we wage abroad, and the utter indifference we have for poor people and people of color at home. He saw the necessity of openly critiquing an economic system that will fund war and will reward greed hand over fist, but will not pay workers a living wage. Five years after the March on Washington, Dr. King was ignoring all those who told him to just stay in his lane, just stick to talking about civil rights.

This is the lingering challenge that King posed: Get out of your lane. Our task, Alexander urges, is to begin connecting the dots between issues that we feel passionately about and other social wrongs that may seem far afield but that share the same systemic roots. Alexander does not wag a scolding finger at her readers; she is self-critical of what she considers her own too-narrow focus:

Yet here I am decades later, staying in my lane. I have not been speaking publicly about the relationship between drones abroad and the war on drugs at home. I have not been talking about the connections between the corrupt capitalism that bails out Wall Street bankers, moves jobs overseas, and forecloses on homes with zeal, all while private prisons yield high returns and expand operations into a new market: caging immigrants. I have not been connecting the dots between the NSA spying on millions of Americans, the labeling of mosques as “terrorist organizations,” and the spy programs of the 1960s and ’70s specifically the FBI and COINTELPRO programs that placed civil rights advocates under constant surveillance, infiltrated civil rights organizations, and assassinated racial justice leaders.

Alexander is not suggesting that we abandon the issues we know intimately and are engaged with, but that we deepen our work by connecting our concerns to issues that might at first seem disconnected yet, on more careful examination, are linked together. For example, President Obama brought the United States to the brink of bombing Syria because of President Assad’s alleged use of chemical weapons against civilians, especially children. The actions of the Syrian regime are despicable; chemical weapons are horrific and immoral. Equally despicable, though, is the chemical warfare waged against children here at home. What about the documented birth defects of children living near mountaintop mining sites in West Virginia? What about the mercury poisoning of children here and around the world, thanks to burning coal for energy? Because of a host of factors connected to poverty and racism, deaths from asthma are two to three times greater for African Americans than for whites and children are hit the hardest. And what about the ongoing toll in Vietnam from the toxic warfare waged by the United States, especially through Agent Orange, or the white phosphorous and depleted uranium that the United States used while laying siege to Fallujah, Iraq, in 2004? In countless ways, it has been and is the unspoken policy of the U.S. government and multinational corporations to wage chemical war on children. The welfare of children is subordinated to the imperatives of corporate profits and making war which, too often, go hand in hand.

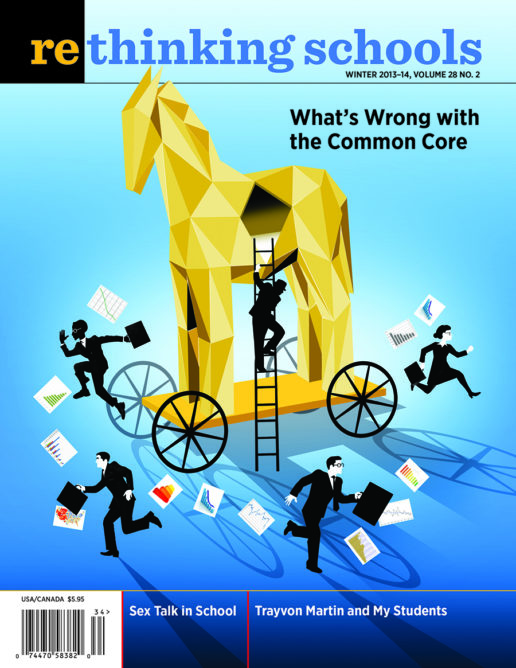

So when we seek to defend children from the abuses of standardized testing, biased curricula, school closures, unequal and inadequate school funding, and the like, we also need to consider how these hurtful practices are part of a system that values profit and power over childhood and is willing to use violence to secure its ends.

This may move us out of our organizational comfort zones, but the deeper we go, the more allies we’ll find, and the greater the likelihood of effecting the kind of basic social changes we need to address the entire constellation of injustices we face. This is what Alexander saw in King’s post-March on Washington work:

In the years that followed, he did not play politics to see what crumbs a fundamentally corrupt system might toss to the beggars of justice. Instead he connected the dots and committed himself to building a movement that would shake the foundations of our economic and social order, so that the dream he preached in 1963 might one day be a reality for all. He said that nothing less than “a radical restructuring of society” could possibly ensure justice and dignity for all. He was right.

Indeed he was. And this is our challenge as teachers, counselors, teacher educators, parents, and education activists concerned about schools and the welfare of children. Yes, we need to rethink schools; however, we really need to rethink our entire society. We need to recognize that the same interests that regard education as a business, schools as centers of potential profit, parents as consumers, and teachers’ unions as an obstacle to corporate control, approach every arena of life with this same exploitative zeal.

As Michelle Alexander urges, we need to connect our grievances and, as importantly, our hopes for a better world with others who are also suffering under the weight of what Dr. King called the “giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism.” We need to begin to see ourselves as part of one movement that is constantly connecting the dots, constantly seeking to imagine and enact a more just social and economic system.