Editorial – Building New Hope

Illustrator: Chris Mullen

It’s hard to find reasons for hope in the education wars these days. Brutal budget cuts and data-drenched testing schemes are enough to make progressive activists believe that “rethinking schools” is a pipe dream. And, of course, the more we sense that resistance is futile, the more the privileged and powerful will carry the day—in education, as in every other arena.

But recent events in Milwaukee, Wis., offer hope to despairing teachers, parents, and education activists throughout the country. Since last August, a remarkable struggle has unfolded in which grassroots organizing has stopped what appeared to be an inevitable mayoral takeover of the public schools.

Milwaukee seems an unlikely site for a progressive victory. Like many other urban districts in the nation, the city is beset with deep problems—both in the schools and the community. Large sections of the African American community have been suffering depression-like conditions for more than a decade. Racial gaps in school achievement, as well as the city’s rates of childhood poverty and teenage pregnancy, rank among the worst in the nation. Meanwhile, school politics have been dominated by privatizing forces for two decades. Over the years, the right-wing Bradley and Walton foundations have successfully pressured politicians—Democrats and Republicans alike—into expanding Milwaukee’s school voucher program into the nation’s largest.

Last summer Wisconsin’s Democratic governor, Jim Doyle, and Milwaukee’s Democratic mayor, Tom Barrett, with the support of U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, announced that the solution to Milwaukee educational woes was a mayoral takeover of the school system.

Initially this seemed like a slam-dunk. Mayoral takeovers are a national trend, promoted heavily by Duncan, who told the Associated Press last spring that he “will have failed” if, when his tenure is up, more urban districts aren’t in mayors’ hands. Besides claiming that mayoral control would increase accountability, proponents of the plan argued that it would curry favor with Duncan and almost guarantee Wisconsin’s selection as a recipient for the much-sought Race to the Top funds. When pressed by opponents to explain how a mayoral takeover would help the students of Milwaukee, the mantra became “Something has to be done in the Milwaukee Public Schools.”

The first proposal was to eliminate the school board altogether. The immediate uproar was so strong that the plan was modified to maintain an elected school board but shift virtually all power to the mayor, including the power to appoint the superintendent, determine the budget, and negotiate all labor contracts.

The governor and mayor lined up support in the state legislature, and the daily newspaper ran articles hailing dramatic school improvements in cities where mayors have replaced elected school boards.

But activists in Milwaukee started to organize—both to defend the democratic rights of the city’s African American and other marginalized residents, and also to demand authentic reform based on parent and community involvement.

Within weeks the Educators’ Network for Social Justice (ENSJ) and the NAACP convened the Coalition to Stop the MPS Takeover, the largest education-focused coalition in Milwaukee since the desegregation struggles of the 1970s.

The coalition—28 organizations strong—included teachers, parents, neighborhood association members, pastors, current and former school board members, community and union activists, students, and a few politicians. Meetings were at times contentious since the coalition brought together individuals and organizations with serious past differences. The differences were worth overcoming, members agreed, because significant changes had to be made to improve the Milwaukee public schools, but a mayoral takeover wasn’t one of them.

Members of the African American and Latino communities viewed the matter as a question of democracy. “We have struggled for over 100 years to protect and sustain our right to vote,” explained Jerry Ann Hamilton, president of the Milwaukee branch of the NAACP, “and we are not going to allow our rights to be taken away from us now.”

Ultimately the coalition united on three goals: oppose the mayoral takeover, protect and defend voter rights, and invest in parent and community involvement in the schools.

The coalition organized rallies at city hall, attended public forums, picketed the homes of individual legislators, and held press conferences. Members distributed thousands of fliers, appeared on local radio and TV shows, and lobbied at the state capitol.

It was an uphill battle. The coalition was fighting not only the powerful Democratic governor and mayor, but also the mainstream media, which refused to acknowledge the coalition’s activities or even existence in print.

Democrats for Education Reform and Education Reform Now—New York City-based groups whose boards of directors include major financial investors and supporters of private charter schools—also publicly advocated for mayoral control in Milwaukee and coordinated their efforts with the local business community.

One aspect of the coalition’s strategy was education—of its own ranks and the greater community. A school board member started a blog that acted as a resource bank. Other groups ran websites. Union activists from Chicago came to explain the negative consequences of mayoral control in their city. This led to better informed coalition members and organizers, and also helped shape the messages of sympathetic politicians.

The organizing and alliance-building paid off. The folks pushing mayoral control were unable to out-organize the community and labor activists. A culminating event was a January hearing in front of the State Senate Education Committee. During the 11-hour hearing, the sentiment was overwhelmingly opposed, with 81 speakers against the proposal and 20 in favor. This didn’t stop the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel from reporting the following day that “members of the public at the hearing were fairly evenly divided.”

At the end of January, the Wisconsin Assembly voted to close the special session of the legislature convened by the governor to push through mayoral control. The governor refused to admit defeat, but leading legislators announced the play was “dead.”

Even before word of the victory reached the coalition, it started planning which proactive reforms should be the next step.

“We should thank the governor and mayor for bringing us together,” one community activist summed up. “Based on our victory, we can now go forward—not to fight against something, but to fight for what the kids really need in this city.”

What can we learn from the coalition’s success? A key component of that success was the patient organizing and coalition building that at times are neglected when activists focus mainly on large mobilizations. Public demonstrations were an important ingredient of the Milwaukee experience, but building relationships and focusing on a deep understanding of the issues laid the foundation.

Even more basic to the success in Milwaukee was the simple, yet often elusive, recognition that, even in difficult times, believing that people can change reality is essential.

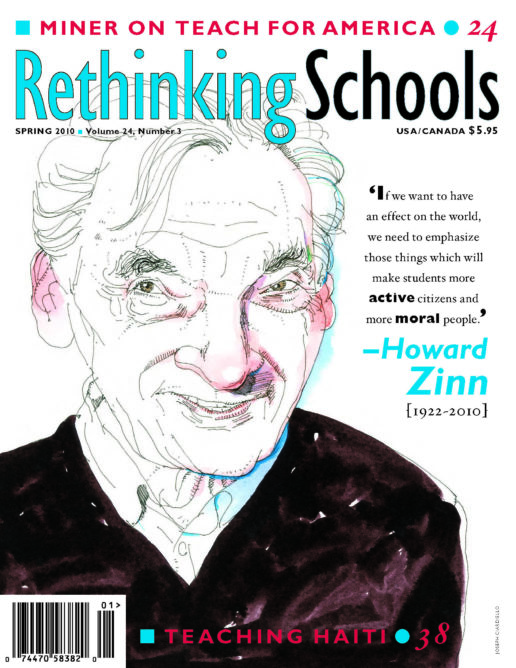

As Howard Zinn wrote, “Everything in history, once it has happened, looks as if it had to happen exactly that way. We can’t imagine any other. But I am convinced of the uncertainty of history, of the possibility of surprise, of the importance of human action in changing what looks unchangeable.”

The success of the Coalition to Stop the MPS Takeover can be a lesson for all of us. We, the people, can shape our futures. We must.