Ecological Footprint Calculators Are Bad for the Environment

For years, I would coax my 9th graders into the dreary, windowless computer lab for 10-15 minutes so they could complete an online ecological footprint calculator. I wanted students to see that first-world consumption patterns were unsustainable.

Students’ reactions to the activity were formulaic. My mostly white, mostly affluent students expressed shock that if everyone on the globe lived like them, we would need four (or five or six) Earths.

One student would say something like “Wait, Ms. Wolfe, so if we ended poverty, the Earth would collapse?”

Another student might say, “This is why we need fewer people; the Earth is overpopulated.”

To which another student would (correctly) retort: “No. It means people in rich countries need to consume less.”

I appreciated how the quick, engaging activity invited students to reflect on the idea of “development.” I liked that it challenged students to redirect their focus from what needs to happen there, to what needs to happen here.

But after a few years, I abandoned the footprint calculator. I didn’t stop to think too much about what made me uneasy about the activity; I just knew it felt wrong. Too simple. A bit like a trick.

Why We Should Skip the Calculator

The first and most essential flaw of the footprint calculator is its basic metric: a footprint. For those who have never taken one, I encourage you to head to the internet, search “Global Footprint Network,” and take the quiz I used with my students. You will find catchy graphics, and questions like “How often do you eat animal-based products?” “Compared to your neighbors, how much trash do you generate?” and “What is the size of your home?” At the end of perhaps a dozen questions, the algorithm spits out your results: “If everyone lived like you, we would need 3.6 Earths.”

The activity’s punchline: How my students and their families navigate choices related to their consumption is the critical determinant of whether the Earth remains habitable.

But that is wrong.

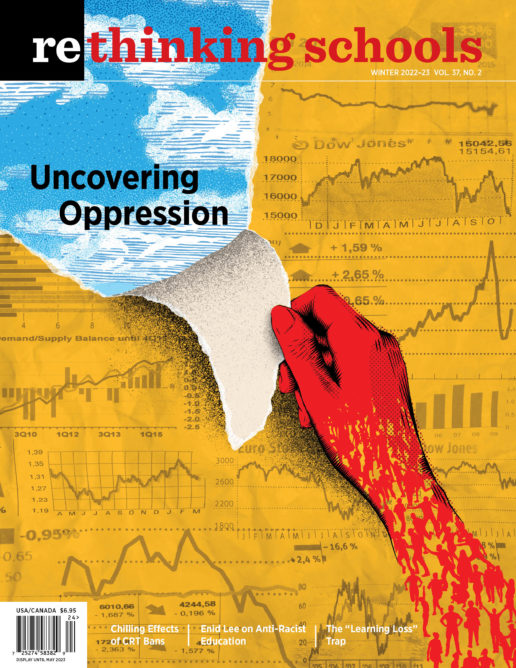

The real authors of environmental degradation were — and remain — entirely absent from the activity. Where was the system of private property that turned the Earth into a commodity to be mined, drilled, burned, and sold for profit? Where were ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron and the 96 other companies that account for 71 percent of global greenhouse emissions? Where were the governments of the world’s richest countries who enable capitalists to prioritize profits over the Earth? The footprint calculator asks none of these people or systems to answer for their consumption; there is no authority figure marching them down to a musty computer lab to account for their behavior. The activity left my students feeling vaguely guilty — even ashamed; but that shame should not be theirs to carry. My students did not build this world. And the footprint calculator does nothing to help them ask who did, why it is shaped as it is, and how it might be redesigned and rebuilt more justly.

The footprint calculator foregrounds “choices” while obscuring their social determinants. The calculator asks how far we travel by car each week or by plane each year, but not about the conditions that shaped those transportation habits. Last year, as school buildings reopened during the pandemic, my phone would buzz with alerts from my child’s school that bus service was once again canceled due to a “shortage of drivers.” Policy choices created that “shortage”: obscenely low wages and dangerous pandemic working conditions. I did not “choose” to drive my kid to school, burning fossil fuels and adding to the already-bad air pollution in our city. No. Choices were made to reopen schools during a deadly pandemic. Choices were made over decades to disinvest from public schools. And those choices narrowed the available options for me and other families, including those who had access to no transportation at all.

The calculator makes no attempt to account for questions of power — who makes the system-level choices that affect everyone else’s choices? It ignores why people act as they do. In this regard, the ecological footprint calculator seems committed to the status quo. If its questions helped students recognize that our “choices” are not natural, but the outcome of political struggles, it would be an invitation to imagine what might be different, and how they might demand a different set of choices.

The “results” page of the Global Footprint Network’s calculator invites you to click on a button called “solutions.” In the category of food, it reads “Can you be a smarter shopper and reduce food waste? Can you try a new vegetarian recipe once a month? Once a week?” In the renewable energy category, it asks “Can you take transit, bicycle, or walk instead of driving solo at least once a month? Once a week?” These bogus suggestions are familiar; they are part of the dominant environmental discourse that permeates everything from advertising to children’s books: If only we drove less, planted more trees, stopped using plastic shopping bags, went vegan, took shorter showers, and drank from reusable water bottles, we could save the planet. But we cannot “individual choice” our way out of a fossil economy. Saying that tweaking consumer behavior will not meaningfully impact the environmental crisis is not the same thing as saying that what we do doesn’t matter. What we do matters a lot. But the “we” must be movements, not individuals working alone. And the actions we take must aim toward the transformation of systems, not an accommodation to them.

One exception to the calculator’s tendency to ignore systems is under the “population” category. The site reads:

Addressing population size is essential to creating a sustainable future for all within our planet’s ecological budget.

You can choose the size of your family to affect our long-term Footprint.

Support women’s rights and access to family planning.

“Women’s rights” is a nod to the existence of patriarchy — a system. And a generous reading of “family planning” might imply universal access to reproductive health care — a proposal that would require systemic transformation. Unfortunately, this is systemic change in the service of an insidious narrative about “overpopulation”: The Earth’s resources cannot sustain an increasing global population and the solution is to reduce the number of people.

Dakota Schee and Varsha Nair explain this narrative’s dangerous logic at the Greenpeace website:

The Population Bomb, a book which first popularized this idea, was based on the author Paul Ehrlich’s experience in a crowded city in India. It advocates for incentives and coercion to control the population — specifically targeted at non-white people. Even today when people talk about overpopulation, they are often talking about China, India, and other primarily non-white countries in the Global South. In the United States, “population control” has come in the form of forced sterilization of Black and Brown mothers. It has been used to justify ecofascist attacks, like the El Paso mass shooting, where the white supremacist shooter cited anti-immigration rhetoric based in the overpopulation myth to justify targeting and killing immigrants . . .

The Global South — with the highest levels of population growth are not the ones overconsuming the Earth’s resources; in fact, they have done the least to cause the Earth’s destruction yet shoulder its worst impacts. The overpopulation argument obscures the real villains of the environmental crisis — billionaire CEOs and corporations — and scapegoats their victims.

And what of the questions not asked by the footprint calculator, questions critical to how radical transformation happens? The footprint calculator does not ask “How often do you meet with friends, family, colleagues, and acquaintances to share knowledge about the environmental crisis and plot ways to take action?” The footprint calculator does not ask “How many boycotts would you say you join every year?” or “How likely are you to divest your savings from banks that profit from the fossil fuel industry?” The footprint calculator does not ask “How often do you respond to calls to act in solidarity with Indigenous-led campaigns to protect the water and land?”

Our students do more than consume. They talk and laugh and sing and dance — albeit often on TikTok. They babysit their siblings. They write poetry and spend time listening to their grandparents’ stories. They study butterflies and bake cookies and dream of kayak trips. And they have the capacity to join — or create — movements for justice. Educational tools that reduce meaningful human action to consumption — as the ecological footprint calculator does — do not belong in our classrooms. Students do not need more anemic “solutions” — meatless Mondays! — that, in Naomi Klein’s words, “show people how they can change without changing anything at all”; and they certainly don’t need white supremacist “solutions” predicated on population control.

These calculators command students to look at their own footprint and use less; our curriculum should invite students to look toward each other and demand more.