Tax the Rich, Fight Climate Change

Column: Earth, Justice, and Our Classrooms

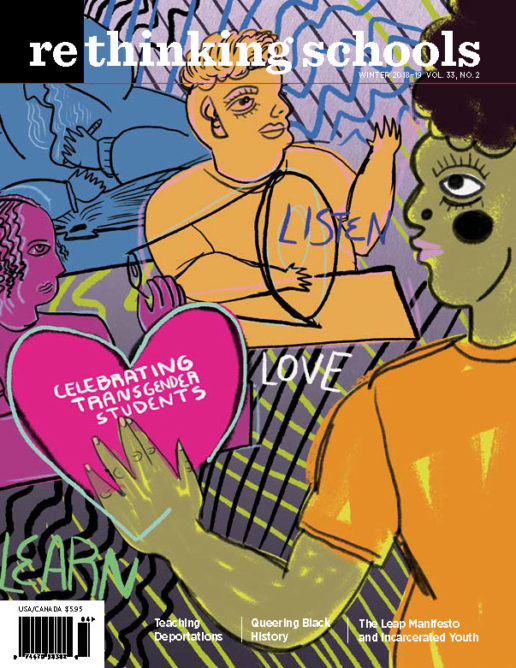

Illustrator: Michael Duffy

Following the 2018 midterm elections, national media missed one piece of very good news. By a margin of almost two-to-one, tens of thousands of Portland, Oregon, voters approved an imaginative clean energy initiative that offers a model for the rest of the country — at the ballot box, but also in our classrooms.

Work on Portland’s Clean Energy Fund began in February of 2016 in a church basement when representatives of the Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon (APANO), the Native American Youth and Family Center (NAYA), Verde (a community-based environmental organization), the Coalition of Communities of Color, the NAACP, and 350PDX (the local affiliate of 350.org) met to discuss how work to fight climate change could simultaneously address racial and economic justice and create living wage jobs. The initiative was the first ballot measure in Oregon’s history launched and led by people of color. And it’s what we need a lot more of: conversations, activism (including curriculum) that lead people to recognize that the “just transition” away from fossil fuels can also be a move toward a society that is cleaner, more equal, and more democratic.

The Clean Energy Fund will be supported by a tax — technically, a surcharge — of 1 percent on corporations with gross retail receipts nationally of $1 billion and at least $500,000 in Portland. Food, medicine, and healthcare are exempt. A 1 percent tax on the 1 percent. Corporations affected include big retailers like Walmart, Target, J. C. Penney, and Best Buy, but also the media behemoth Comcast, which dominates Portland’s cable market. Organizers estimate that the tax will raise $30 million a year. The money will go to a fund dedicated to clean energy projects — renewable energy and energy efficiency — targeted explicitly to benefit low-income communities and communities of color. The fund will also support regenerative agriculture and green infrastructure projects aimed at greenhouse gas sequestration and sustainable local food production.

An important component of the new initiative will be creating clean energy jobs that “prioritize skills training, and workforce development for economically disadvantaged and traditionally underemployed workers, including communities of color, women, persons with disabilities, and the chronically underemployed.” Workers will be paid more than $20 an hour, at least 180 percent of minimum wage.

Khanh Pham, an organizer with APANO, recently spoke about why her organization helped create this initiative: “Asians and Pacific Islanders are the first and hardest hit by climate change. Many of our members, particularly our immigrant members, are struggling to find living wage work. This ballot initiative allows us to tackle both climate change and growing inequality at the same time.”

The tax targets rich corporations not just because they are rich, and can easily afford to pay — although that would be reason enough — but also because of their climate-hostile practices: selling heavily packaged non-recyclable products and their carbon-intensive shipping of goods long distances from factories often powered by the dirtiest fossil fuels. Levied only on giant retailers and not on local businesses, the measure also represents a way to favor local production and sales.

Classroom Implications

Portland’s successful clean energy campaign offers lots of lessons for how we can reframe the climate crisis in our classrooms. So often just the mention of climate change is accompanied by a sigh of despair. But the Portland initiative shows that we can shift from what often feels like a journey into dystopia to a narrative of social transformation. Yes, our curriculum should focus on the increasingly scary greenhouse gas trajectory, but our students are unlikely to be moved solely by horror stories of raging wildfires, melting glaciers, rising seas, monster hurricanes, and yes, dying polar bears. We also need to engage their imaginations, their hope for a better world. The most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report calls for “rapid, far-reaching, and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society,” which need to “go hand in hand with ensuring a more sustainable and equitable society.” This can and should be at the heart of a climate change, a climate justice, curriculum: imagining how a just transition away from fossil fuels can create a healthier and more equal society.

The multi-organizational conversation that led up to Portland’s clean energy initiative began from the standpoint of social justice — what has been called an “environmentalism of the poor.” Instead of a conservative curriculum that asks students to consider all they will lose as a result of global warming, which is an implicit embrace of the status quo, we need a radical curriculum that asks students to consider all they will gain from a just transition away from fossil fuels.

Portland’s campaign to establish the Clean Energy Fund had solidarity at its heart — people in diverse communities coming together to pursue a just transition that makes life better for the vast majority of people. Our “just transition curriculum” also needs to have solidarity at its heart. As we make activism common sense in our classrooms, we need to help students practice thinking about the ways communities can collaborate across historic borders toward a common future. This is what Adam Sanchez, Tim Swinehart, and I attempted in a role play we wrote, “Teaching Blockadia: How the Movement Against Fossil Fuels Is Changing the World,” posted recently at the Zinn Education Project. In the role play, we divide students into seven groups, all of whom seek to protect their communities from the impact of fossil fuels. For example, some of the groups include ecoCheyenne, Northern Cheyenne tribal activists in Montana, fighting coal strip-mining and methane development; Our Hamburg, Our Grid, the Hamburg, Germany, group that spearheaded the campaign to seize the electrical grid from private utilities; the “Warriors of Sompeta,” in Sompeta, India, who organized to shut down development of a coal-fired power plant in their community; and the Beaver Lake Cree Nation, struggling against tar sands oil development on their land in Alberta, Canada.

In the role play, students learn about the peculiarities of their situations, but also rotate from group to group to encounter different struggles and to figure out how they can work in solidarity with each other toward a green future — one not dominated by fossil fuels or the imperatives of for-profit corporations. Students-as-activists come together to demonstrate at a “Fossil Fuels for a Better Future” gathering, give speeches, and display posters they’ve created on the vision that unites their activism. Part of students’ assignment is to visually represent how at least two of the anti-fossil fuel struggles are connected and can support one another.

Portland’s just-approved clean energy initiative will help schools in some obvious and immediate ways. The fund can support the placement of solar panels on school buildings; it can support revitalized school gardening and farming programs; and support programs that train young people in green building design, weatherization, and solar installation. But it also offers teachers a paradigm shift on climate education. It shows that when we begin to explore the roots of multiple injustices — from climate change to income inequality — we can begin to imagine the outlines of a movement and a curriculum powered by solidarity.