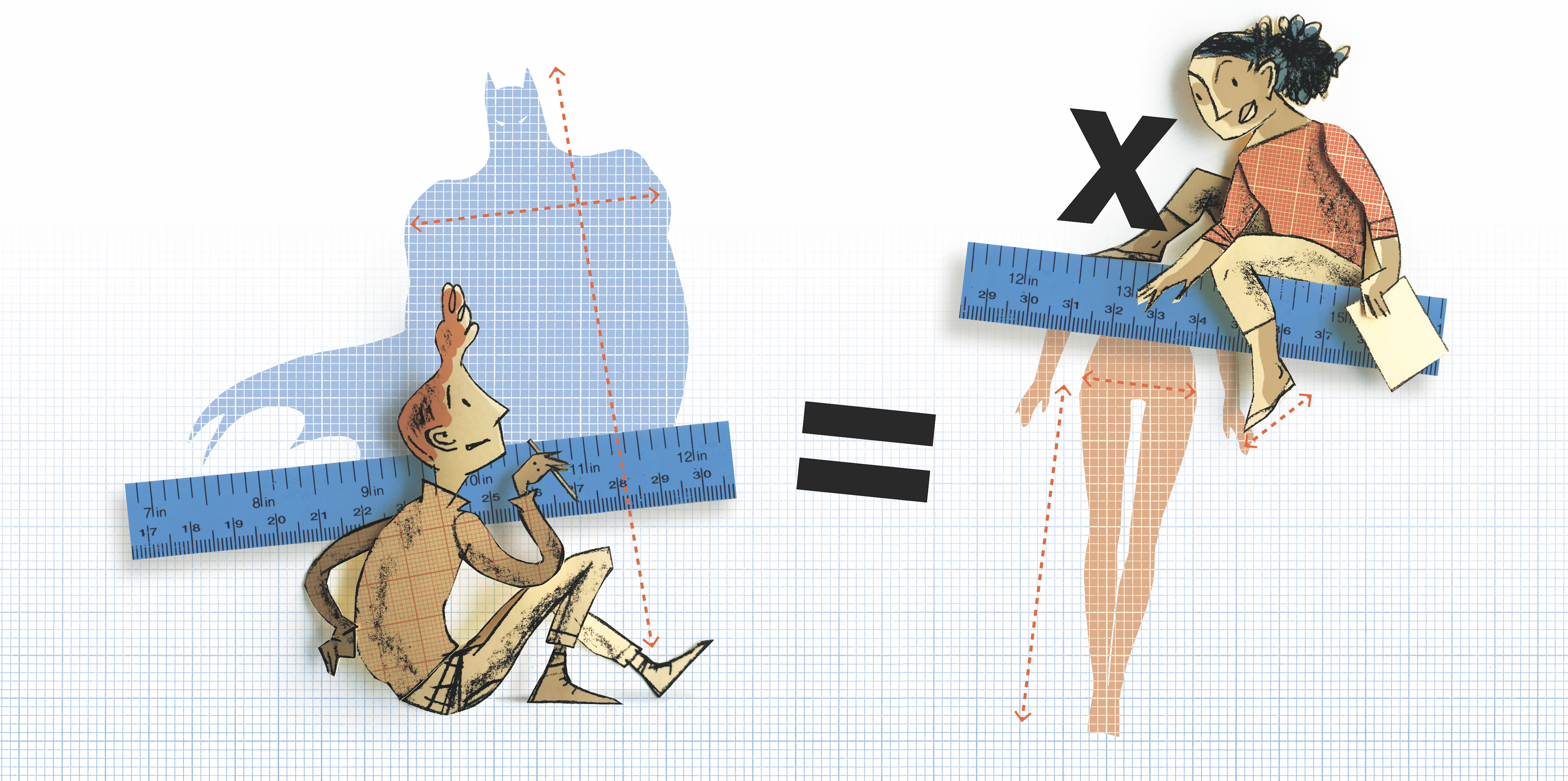

“Do You Have Batman Shoulders?”

Middle school math students explore the disproportions of their favorite childhood toys

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

Thirteen-year-olds dart around the math room trying to decide which doll or action figure to play with as I instruct them to sit no more than three to a table. We are in the middle of a unit on proportional reasoning, and although they are admonishing each other not to remind me that we’re supposed to be learning math, they’ll soon be working together to figure out how (little) these iconic characters compare to real live humans.

The idea for this investigation started percolating when a colleague gifted me a copy of Rethinking Mathematics that she found at a conference book fair. One curricular piece that immediately captured my attention described students using proportional reasoning to create life-sized comparative overlays of Barbie’s body and tracings of a real girl’s body on butcher paper. It was a compelling idea to use math to lay bare the extreme distortions we internalize about what bodies should look like . . . and it made me uncomfortable. My head echoed with hurtful comments students might make about each other’s bodies and I wondered how I could engage my students in the thinking without risking them getting hurt.

I talked the activity over with friends and family, seeking advice on how to make it safe for girls in my class to have their bodies traced. Someone suggested that maybe I could split my class by gender and have the boys compare their outlines to those of action figures. The action figure suggestion was interesting, but, having thought a lot about how to support transgender and non-binary students, splitting my class by gender is not something I would ever consider. I also quickly realized that it wasn’t the boys’ presence that made the activity feel unsafe; I was actually most nervous about what the girls might say in their own heads by virtue of comparison.

Years passed and the Barbie lesson continued to surface in my mind, unresolved. In 2013, I read a posting for a Philadelphia social justice math inquiry-to-action group. The idea of being in a room with other math educators to talk about connecting curriculum and social justice was exciting. I decided to host a similar weekly group in New York City that February and March, drawing a small rotating cast of inspiring educators from Harlem to Brooklyn. Talking out the dilemma I’d been facing around the Barbie lesson with other math teachers helped me to articulate where I was stuck. The original lesson compared three-dimensional dolls and people in a two-dimensional plane. There aren’t any geometric formulas with which to convert average waist size and chest size measurements into dimensions that would land on a flat outline of a figure, so working in two dimensions required the activity to focus on comparing the body of someone we could actually trace with the printed outline of the doll. A teacher at the table asked me why I was attached to the idea of using two-dimensional representations and it catapulted my thinking over the wall of the box I’d been stuck in. I realized that if I could get a set of dolls and action figures, I could engage my students with the characters in three dimensions instead and compare them to any person whose measurements we could procure (a teacher’s shoulder width, a celebrity’s height, average head size for American men, etc.).

I drafted an email to my community and posted a flyer: “Support our math program — donate your old Barbie dolls & action figures!” Individual characters began to show up in my mailbox. Most of the characters were more disproportionate than I could have imagined, and, initially, all of the characters were white. When we started working with the figures, I apologized to my students that my donated collection didn’t reflect the diversity of our classroom and stated that I would love to have a more diverse assemblage. As a result of that explicit conversation, several Black and Brown dolls joined the group.

For each figure, I developed a pair of questions, asking students to scale a disproportionate body part to the size it would be if the doll were human height and also asking them to calculate the height of the doll if that body part were “average” American size. Because math is already a subject that causes many students anxiety, and because so many middle school students are uncomfortable with bodies (their own, each other’s, everyone’s), I made a point of not writing questions about particularly sensitive body parts like busts, butts, and waists.

“You will be working with the people at your table to answer the questions at your station. The dolls and action figures are meant to be played with, but please be gentle with them so that future classes will also be able to use them. Each table should have measuring tapes, calculators, dolls, and a set of questions. Is anyone missing anything? Great. Let’s get started.”

Lani and Samia are working with Barbie. The first question reads: “Size 8 is one of the top-selling women’s shoe sizes. If Barbie’s feet were that big, how tall would she be?”

Samia reaches for her measuring tape to measure the height of the Barbie doll. She calls me over to ask, “Should I measure in inches or centimeters?”

“You get to decide!”

She consults with Lani and they decide to work with inches. While Samia measures the doll, Lani looks at the shoe size chart provided. The table contains much more information than the basic two-column tables most math textbooks focus on; it compares foot length measurements in centimeters and inches to U.K., European, U.S. women’s, and U.S. men’s shoe sizes. Many of my students will be able to look at the chart and parse which columns to focus on, but for some of them this is a big cognitive leap and Lani wants support.

“What information do you need from the table?” I ask.

“I need to know how big size 8 feet are.”

“Can you find size 8 in the column titled U.S. women’s shoe size?”

“Found it.”

“Which column do you want to compare it to?”

“Inches . . . oh, I get it! Women’s size 8 feet are 9.65 inches long!”

The girls use the numbers they’ve collected to set up a proportion, using a word fraction to guide them.

foot length/height : 1.3/11.5 = 9.65/x

I know that Barbie’s feet are less than an inch long, so I ask Samia to show me how she got 1.3. She pulls out the tape and counts the tick marks to 13.

“13 tenths,” she says.

“Is that mark more or less than a whole inch, Samia?”

“Less . . . I guess 1.3 doesn’t make sense.”

“Centimeters are divided into 10 parts, but how many increments are there in an inch?”

She counts 15 little tick marks.

“To get to the end of the inch you’ll have to count that last segment . . .”

“So Barbie’s foot is 13/16 of an inch long?”

“Yes. How could you write that as a decimal?”

She reaches for her calculator . . . 13÷16 = .8125

The girls fix the number in their proportion.

foot length/height : .8125/11.5 = 9.65/x

Samia cross-multiplies to solve while Lani looks for the scale factor between .8125 and 9.65. Both girls find that to the nearest inch x = 137.

“Barbie would be 137 inches tall,” Lani reports.

“How many feet would that be?” I ask.

“There are 12 inches in a foot . . .”

Lani reaches for her calculator:

137 ÷ 12 = 11.4

“11 feet 4 inches?! That doesn’t make sense!”

But Samia’s calculator also reads 11.38.

“Seems Barbie’s feet are pretty disproportionate to her height. I know lots of people with size 8 feet, but I don’t know anyone more than 11 feet tall! Also . . . 11.4 feet isn’t the same as 11 feet and 4 inches. Remember how the inch isn’t divided into 10 parts? Neither is the foot.”

“We should have used centimeters!”

“Lots of people prefer them. . . . If you took out 11 feet from 137 inches, how many inches would be left over?”

“11 x 12 is 132 . . . which means . . . there are 5 inches left over? So, she’d actually be 11 feet 5 inches?”

“Yes. And, for perspective, our classroom is only about 9 feet tall.”

“Whoa!”

They turn to the next problem: What size shoe would Barbie wear if she were 5’4″ tall, the average height for women in the United States?

They already have Barbie’s measurements, but they’ll need to convert 5’4″ to inches and think through how to set up the proportion. Once they complete their calculations, Lani calls me back to their table.

“Flannery . . . what if the foot length isn’t on the table?”

“Well, where would it fit?” I ask.

“It would have to be smaller than size 3.”

“Do you know anyone your age with shoes smaller than size 3?”

“No!”

“That’s why they decided not to put it on the table. Remember how Barbie was really tall when she had size 8 shoes? Her feet would have to be really small if she were average height. You can write down that it’s smaller than size 3 or that Barbie’s shoes would be so small that they’re off the charts.”

At the other tables, students are engaged in similar work with Buzz Lightyear, Bratz dolls, G.I. Joe, Batman, Robin, Ant-Man, Aquaman, Ariel. I interrupt them: “Great work today. I heard a lot of good questions and witnessed people helping each other. We’re going to continue our work with the figures tomorrow. I posted some articles about dolls on the homework website to give our work some context. Your homework is to choose one article to read. We’ll discuss them at the beginning of class tomorrow.”

I didn’t think to give this assignment the first year I taught this lesson, but I noticed that most of my students weren’t thinking about why the disproportionality of the dolls mattered. This homework assignment helped to connect the activity to other conversations they’ve had about body image and the media.

Here’s what I shared with my students:

- “Barbie’s not the skinniest doll on the block” from Slate.com in February 2014, which compares Barbie’s height, bust, and waist measurements to those of other popular dolls, multiplying them all by the playscale of six to get their human-size dimensions. Despite the article’s title, and the finding that Barbie may not be the most disproportionate doll on the market, the article concludes that, precisely because other dolls have obviously disproportioned heads and Barbie looks so human, she still may be sending a more negative message to girls who play with her than other dolls do.

- “Where’s Ken? The abandonment of men in body positivity” from Newsweek in February 2016, which discusses the advances that have been made to make dolls for girls more realistic, as the action figures boys play with have become more exaggeratedly skinny and muscular.

“What stood out to you from the pieces you read last night?” I ask the next morning.

Alex: “I read the article about Ken and it said people talk so much about the messages girls get that they came out with new Barbies that look more like real people, but that there isn’t as much talk about boys and the toys they play with — and nothing has changed about Ken . . .”

Carl: “But action figures aren’t supposed to look real. I’m not sure that it really makes a difference. I mean, I don’t feel like I have to look like Captain America just because I’ve played with him.”

“What do the rest of you think about that?” I ask.

Rehana: “The article about Ken said that part of the problem is that he makes girls think that men should look like him and then boys get messages from girls and women about what they’re supposed to look like.”

Ariella: “And just because it doesn’t hurt you, Carl, doesn’t mean it doesn’t hurt other people. There are lots of people who struggle with body image. And even if girls don’t actually think that we have to look exactly like Barbie, she’s one of many ways that girls are pressured to be skinny and have big breasts. We’re getting sold unrealistic images of what bodies should look like all the time. Think about that clip we watched in advisement class about how they make commercials with real live models and then airbrush and photoshop them to make girls skinnier and curvier, make men have more pronounced six packs and jawlines — they even changed people’s skin color . . .”

“Thanks for making those connections, Ariella and Rehana. Does anyone have anything else to add?”

Maeve: “Well, I know that one of the articles said that Barbie’s body is more realistic now than she used to be, but that doesn’t mean she’s sending healthy messages to girls. I wondered what Barbie’s waist size would be if she were my height and, according to my calculations, if she were 5’4″ tall, her waist would only be 19 inches. I’m not sure if stores sell pants with a waist size that small, but it’s definitely not a size that most grown women my height should aspire to be.”

“A 19-inch waist!” I exclaim. “That would look about like this,” I say, forming my hands into an oval. “There’s definitely nobody in this room with a waist that small and you’re right that it would be pretty unhealthy for women to be that size. Thanks for doing those calculations, Maeve! I think it’s important to know that people have been talking about and pushing back on these disproportionate icons for a long time. . . . As you read in some of the articles, public outcry has led to some changes, but many people think that there’s more work to be done. Lots of studies have shown that large numbers of elementary school children are unhappy with their bodies and want to be thinner. That’s really unhealthy and kids didn’t always feel that pressure. Unrealistic images are clearly part of the problem.”

As we get back to our proportional reasoning work, I hear more students share the results of their calculations with each other, exclaiming things like “Whoa! . . .” and “Can you believe . . . ?” On day two they also set up their proportions more confidently and are better equipped to support each other, so I get to spend more of my time pushing students to record their thinking and dig deeper.

In two class periods with the figures, some students have engaged with lots of dolls and action figures while others have worked with only two. It’s OK that they haven’t answered the same number of questions. They have practiced applying their understanding of proportional reasoning and measurement in a non-routine context. Developing proportional reasoning is one of the most important math learning goals we have for middle school students. As grown-ups we might not always write proportions in order to organize our thinking, but we employ this branch of reasoning all the time. It’s how anesthesiologists determine dosages, cooks scale recipes to feed a crowd, and farmers plan seed orders for the crops they want to grow.

To develop our visual storytelling skills and amplify the impact of our work together, we’ll devote the third day of our mini-unit to making posters designed to generate conversations in the hallways about how disproportionate these iconic bodies are. I pull the class back together to prepare them for that work. “You probably remember seeing some posters about these characters at last year’s data fair. We’ll be making ours tomorrow. Your homework for tonight is to decide on a question, complete the calculations in your notebook, and think about what kinds of images you might need to collect to help the viewer understand what you’ve figured out. Please give it some thought. It will be a lot more fun to work on if you pick something that you’re actually interested in.”

The hit of last year’s annual Social Justice Data Fair was 33-inch Batman shoulders, against which everyone from 6-year-olds to the head of school tested out how their shoulders compared. Jesse had investigated how wide Batman’s shoulders would be if he were as tall as our English teacher. Once he’d cut the shoulders out of two pieces of red poster board, written his calculations on them, and figured out how big the head should be, I helped him to print an image of Batman’s head to scale.

This year, without any nudging from me, students talked about how they could make their projects interactive for the younger kids who would be visiting the fair. One of my students decided to make a life-size felt version of Roller-Skating Barbie’s skirt for people to hold against themselves so that they could see just how tiny it would be. Another student made a life-size version of Barbie’s tube top and photographed a 5’4″ friend holding it against himself.

During the poster-making stage, most of my students choose to compare the figures to their siblings, teachers, and other role models. They explore what stands out to them about the characters. In the questions I wrote, I was careful not to ask them to measure their own bodies and I avoided body parts that students might feel awkward (or delighted) about measuring, like Barbie’s breasts. After all of the thinking I’d done to avoid my students having to make their bodies vulnerable, I was surprised, when, in the very first year of the project, one of my students chose to make a poster titled “OMG! Barbie ur waist is so skinny!” that included a photograph of herself with her waist measurement alongside a photo she’d taken of Barbie with the waist size that she’d calculated Barbie would have if she were the same height. Once I got over the surprise, I was excited to realize that I’d created space for her to choose to go there without my having asked anyone to do so. Kalani’s poster, much like the initial project I’d read about in Rethinking Mathematics, highlighted the potential for images to communicate mathematical reasoning and deepen students’ understanding of their calculations. By leaving the assignment open-ended, students get to work within their own comfort zones and surprise me with their creativity.

This project is just one of many opportunities my students will have to explore and question the way society puts pressure on young people to look a certain way. Creating another space for that conversation is what motivated me to develop the project. As ought to be the case with good social justice curriculum and pedagogy, it turns out that the mathematical thinking my students engage in through the project is also much richer than the proportional reasoning work that was happening at my school before this project came to be. And by sharing their work at our data fair, students have an opportunity to teach the community both about proportional reasoning and about the unhealthy messages we receive about what our bodies ought to look like.

Requirements for making the poster

- Title: A question or statement that should read like a newspaper headline.

- Examples from students:

- Barbie would be a negative size!

- Looks like Barbie is . . . out of shape!

- If Batman’s shoulders were as wide as Tom’s he would only be 37″ tall!

- The work you did to find the answer, labeled so that the viewer can follow it.

- A visual that helps the viewer understand the importance of your findings. I encourage comparisons between “average” or “real” measurements and scaled findings.