Preview of Article:

Do I Really Teach for America? Reflections of a Teach for America Teacher

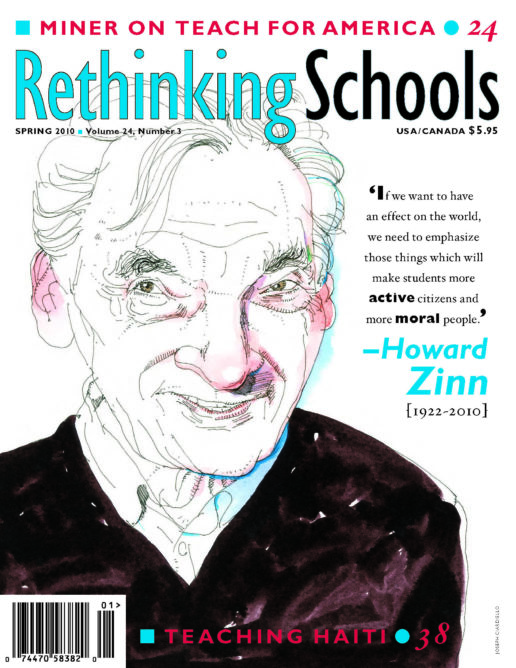

Illustrator: J.D. King

If you know what to look for, it’s not hard to spot a Teach for America (TFA) classroom. Typically, on one wall, a “Big Goal” poster proclaims the class objective: “Students will, on average, achieve 80 percent of their learning goals based on state standards.” On another, tracking charts show the progress of individual students toward meeting those standards. At the front of the class—or, just as likely, crouched over a student’s desk offering help—is the teacher: probably young, probably white, and probably from an upbringing worlds different from the low-income communities of color that TFA targets.

Though my own classroom in Memphis, Tenn., is characterized more by quotes from acclaimed rabble-rousers and stacks of unorganized student handouts, I am one of about 7,300 current TFA teachers—and, if you believe the organization’s rhetoric, offered to us in workshops and featured at TFA’s website, a member of “the new civil rights movement.” I am in my second year teaching high school world history and world geography. For a variety of reasons, at the end of this year I will join the majority of TFA teachers who move on after their two-year commitment.

Most TFA teachers enter the program fresh from the completion of their undergraduate education—I was on a plane to Memphis for the beginning of summer training one week after I graduated from Wesleyan University in Connecticut with a degree in sociology. Very few of us, including me, had formal education training prior to joining TFA. Our ideas of how to teach come mostly from a five-week summer training institute that promises to give new recruits the tools they will need to be successful teachers. The summer institute combines sessions on classroom management, lesson planning, and other aspects of teaching with a daily opportunity to plan and deliver a lesson to a summer-school class under the supervision of an experienced teacher.