Preview of Article:

Dismantling a Community

In Katrina’s wake, a baffling array of school systems has been created. A timeline compiled by Leigh Dingerson, the Center for Community Change

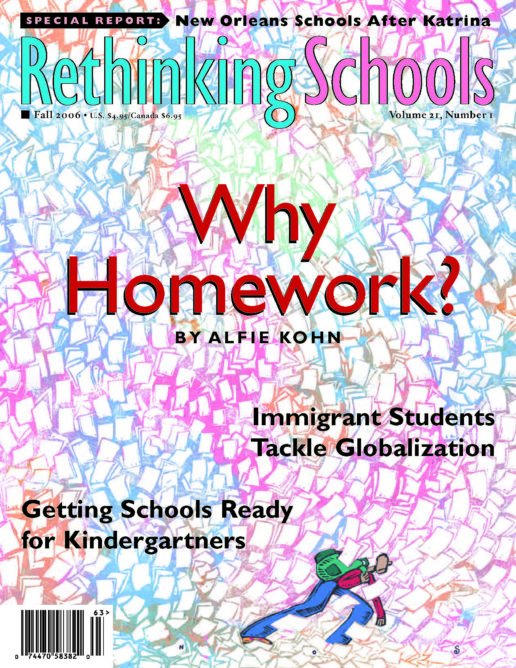

Illustrator: Tony Auth © 2006 The Philadelphia Inquirer / Universal Press Syndicate