Deporting Elena’s Father

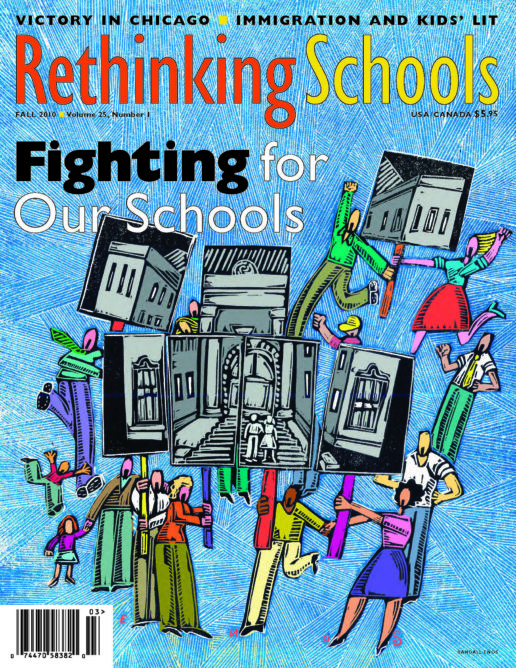

Illustrator: Roxanna Bikadoroff

All over the United States, formal collaboration between U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and local law enforcement under ICE ACCESS programs has deputized local law enforcement agents to enforce federal immigration law. Although no such agreements currently exist in the state of Wisconsin, the Milwaukee County Sheriff’s Office has been collaborating with ICE. The result has been a significant increase (46 percent from 2007 to 2008) in the number of detained and then deported immigrants picked up on minor traffic violations in the county. The Milwaukee County Board of Supervisors heard testimony on this issue at their July 2010 meeting. Unfortunately, they sided with the sheriff’s department and decided not to pursue an intensive investigation. Local community organizations continue to advocate for an end to this collaboration. Rethinking Schools Editorial Associate Melissa Bollow Tempel gave the following testimony at the meeting:

I am a bilingual teacher in Milwaukee Public Schools. Over the years, I have seen many students deal with deportation. People ask me, “How does deportation affect children?” The question I’d like to pose today is “How doesn’t deportation affect children?”

This year I had a student in my 1st-grade class. I’ll call her Elena. She was a natural leader in the classroom and spoke both English and Spanish fluently. She was well liked by her classmates and a natural leader, always organizing games on the playground during recess. Elena’s father was a model dad, the kind who worked hard and spent his free time with his family and his church. Every day he’d pick up his children from school. When Elena saw him approaching the school she’d yell, “Papi!” and run to him. They’d share a big hug and then he’d take her hand and the hand of her little sister and they’d walk home together. He helped Elena complete her homework—she is a very bright little girl—and read to her.

Elena’s mother came to my classroom one morning and asked me if I could write a letter of support to the judge who would try her husband’s deportation case. She told me that Elena’s father, the father of her four children, had gone to work and never returned. She learned later that ICE had taken him into custody. Although she is a U.S. citizen, he was not allowed to return home while awaiting his trial. Of course, I wrote the letter for her, as did the teachers of Elena’s siblings, but it did no good. Elena didn’t see her father again and eventually he was deported. My own daughter was in 1st grade this year and I couldn’t even allow myself to think about the severe impact that losing her father would have had on her.

This brings me to how deportation affects my students. Elena’s mother was forced to send her children to her sister’s house on the other side of town to sleep every night because her husband had cared for the girls while she worked third shift in a factory. Elena’s bright smile and eagerness to learn faded and she became somber, tired, and withdrawn. She stopped participating in class and often asked to stay inside instead of playing with her friends during recess. Elena stopped doing her homework because her father was not there to help her, and her mother had no time between household chores, cooking, and getting the children ready to drop off at their aunt’s house every night. Her mother told me that she slept only three hours during the day while her baby was sleeping. She’d be so tired that she would oversleep and miss the pickup time at the end of the school day. We’d have to call to wake her up.

Mondays were the worst. Elena would come to school after spending some quality time with her mother and family; I’d take one look at her face and know it was going to be a hard morning. On those days I’d let her eat breakfast in the hallway with me while my teaching partner stayed with the rest of the class. Elena would sit on my lap and cry—sob, really—and tell me that she missed her father, that she wanted to talk to him, to see him. Sometimes it would make her feel better to write him letters. She would end them with “Are you coming home?” and draw two little boxes—one for him to check “yes” and one for him to check “no.” Even more heartbreaking were the letters that ended the same way but with a different question: “Do you still love me?”

This summer I have spent some time with Elena and her siblings, trying to give her mother a break. Mostly I’m there because I know that Elena’s having a difficult time with yet another change in her life, the transition from the school to the summer, and she’s lost the regular support of her teachers for the summer.

Elena’s mom told me that they will probably move in with her sister, which means that Elena will have to change schools. Her new school doesn’t have bilingual classes. She’ll have to make new friends and her mother will have to start over, building a support network in the community for her children and herself.

I’m using Elena as an example because this is not a unique story. It has many similarities to the experiences of all my students who have dealt with the deportation of a parent. There is absolutely no way that Elena and the three other children in my class who lost a loved one to deportation were not deeply affected, emotionally and academically. Our students are hurting. Some of them were born here, making them “legal,” and they hope to carry out their family’s dream of a better life. That dream starts with education.

These children face so many obstacles: living in poverty, lacking medical and dental care, and living in homes that landlords don’t bother to repair because they know their tenants won’t report them. Deporting children’s parents creates just another obstacle for them, but this is the one that is the most difficult to overcome.