Deportations on Trial

Mexican Americans During the Great Depression

The Trump administration’s horrifying family separation policies, which are resulting in heartbreaking scenes at the border, in detention centers, in courtrooms, and in our communities, have piqued the nation’s concern about U.S. deportation policy. Of course, deportations are nothing new; Obama was rightly criticized as the “Deporter-in-Chief” because between 2009 and 2016 his administration forcibly removed more than 3 million undocumented immigrants, a rate of removal far higher than any of his predecessors. But the Trump administration has embraced deportation with enthusiastic cruelty and vigor, including the targeting of long-term residents with no criminal record.

As acting director of Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Thomas Homan, explained, “The president made it clear in his executive orders: There’s no population off the table. If you’re in this country illegally, we’re looking for you and we’re going to look to apprehend you.” The massive reach of this effort, the uncertainty and terror it elicits, and the opacity of the controlling laws, recall an earlier time in U.S. history when the due process and human rights of racialized “foreigners” were abused with impunity.

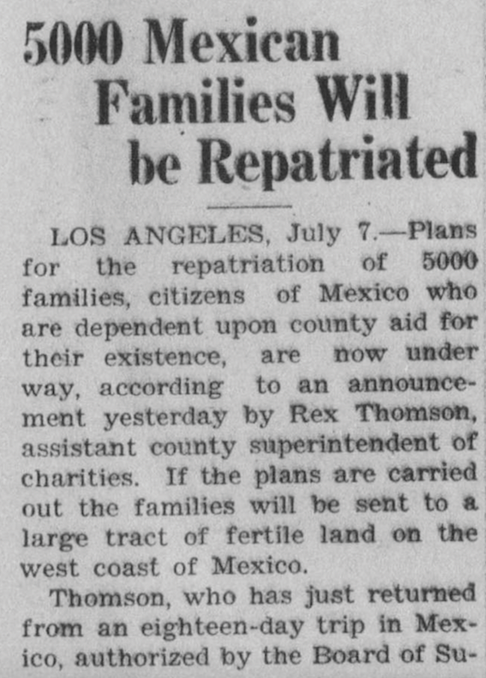

From the late 1920s to the late 1930s, men, women, and children, immigrant and U.S.-born, citizen and noncitizen, longtime residents and temporary workers all became the targets of a massive campaign of forced relocation, based solely on their perceived status as “Mexican.” They were rounded up in parks, at work sites, and in hospitals; betrayed by local relief agencies who reported anyone with a “Mexican sounding” name to the Immigration Service; tricked and terrorized into “voluntary” deportation by municipal and state officials; and forcibly deported in trains and buses to a country some hadn’t lived in for decades and others never at all.

According to Francisco E. Balderrama and Raymond Rodríguez, authors of Decade of Betrayal: Mexican Repatriation in the 1930s, the terrifying raid that took place at La Placita Park in Los Angeles was emblematic of the era. Selected by immigration enforcement officers to inflict maximum psychological impact on the Mexican American community, La Placita was a vibrant cultural hub in an immigrant neighborhood, a place to listen to music, talk politics, socialize. Historian Doug Monroy writes, “In the days before television and radio, if you wanted stimulation and excitement, you went to La Placita.” On a sunny afternoon in late February of 1931, the park was full of close to 400 people when suddenly, the exits were sealed off by immigration agents, some in military olive uniforms, others in plain clothes, wielding guns and batons. The agents demanded everyone in the park line up and show their papers. According to one man in the park, however, papers turned out not to save you. When Moisés González, who did have his papers, handed them to the agent, he pocketed them and detained González anyway.

Though it is hard to say how many people were actually deported as a consequence of raids like La Placita, they succeeded in convincing Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans that they were no longer safe in their communities. Raymond Rodríguez says his own father, a legal resident, decided to leave following the raid, concluding the immigration sweeps posed too great a danger for him and his family. But his wife saw things differently, refusing to leave with their five U.S.-born children. As Rodríguez recalls, his father’s last words to her were “If you don’t go [too] . . . you’ll starve to death and maybe worse.” The family never saw him again. In another case, Angela Hernández de Sánchez was returning from a weeklong trip visiting her relatives in Mexico, which she had done dozens of times since moving to the United States decades before. But this time, when she crossed back into the United States, she was arrested, detained, and subjected to intrusive venereal disease tests. Since Sánchez had been a continuous resident of the United States since 1916, she was not eligible for deportation under current law and all of her children were U.S. citizens. But even with her proof of residence and her negative blood test for venereal disease, she and her U.S.-born children were deported.

Historian Mae M. Ngai argues that this 1930s campaign of mass deportations had little to do with law; it was a program of “racial expulsion” rooted in racism. But unlike other racist and nativist efforts of the era, these deportations were not driven by any signature piece of legislation like the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 or the Immigration Act of 1924. Rather they were orchestrated using a patchwork of federal and local authority, existing but seldom used deportation rules, and simple mob action against a vulnerable population. It is precisely this messiness that is fruitful to surface with students. If no single law or leader ordered these deportations, then why and how did they happen and who or what is responsible for the damage they wrought?

These are the questions I sought to raise with students in the Deportations on Trial lesson. The role play, which uses Bill Bigelow’s “The People v. Columbus” trial as a model, takes as its premise that a crime has been committed.

Before diving into the trial, I spend a class period familiarizing students with the crime. We listen to a wonderful StoryCorps oral history of Ruben Aguilar, “Drafted to Fight for the Country that Hurt Him.” Aguilar tells the harrowing story of being deported with his parents at 6 years old. He remembers the agents storming the house, the train ride to Mexico, and finding himself in a Spanish-speaking country where he did not understand nor speak the language. He lives in Mexico until, as a young man, he receives a draft notice from the U.S. Army. Students also read a 2017 article from The Atlantic, “America’s Forgotten History of Illegal Deportations,” which includes more stories like those of Aguilar, Rodríguez, and Sánchez. As they listen and read, I ask students to take notes using the following questions: What is the crime? Why did it happen? Who is responsible?

The next class period, trial preparation begins. I tell students:

You are charged with the illegal, immoral, and inhumane deportation of more than 1 million Mexican immigrants, legal residents, and Mexican Americans from 1929 to 1939. You terrorized communities, broke up families, and denied people of Mexican ancestry their human and constitutional rights.

Although students are all charged with the same crime, I divide them into six groups. The indicted groups are the Federal Government, Police and Immigration Agents, Business Owners Under Capitalism, the American Federation of Labor, the Racist Media, and the Deportees. With the exception of the Deportees, all of these groups are complicit in the deportations. With this kind of trial lesson, the goal is not to lead students to see a single actor as guilty, but for them to understand and analyze how different groups and systems are responsible in different ways.

After students have clarified the basic idea of the trial, I ask them to dig into the indictments, starting with their own. I say, “As you read over what you are accused of, highlight or underline places where you can offer a defense, where you can convince the jury that the prosecutor is wrong.” I instruct students not just to consider how they will defend themselves against the charges, but also how they might convince the jury another group is more guilty than they. In the Federal Government role, part of the indictment reads:

But now, the United States is in an economic crisis, caused partly by you. You did nothing to stop businesses from setting high prices, keeping wages low, and attacking labor unions. Now, congressmen are seizing on white people’s racial fears and prejudices to propose all kinds of new laws that will stop immigration from the south and deport more Mexican immigrants back to Mexico. . . . Some of these laws have passed and some have failed, but the message sent by your government is clear: People of Mexican ancestry are not welcome here.

Students in this group quickly identify some lines of defense. For example, in all my classes, the Federal Government group ended up pursuing some version of the following argument: “In a democracy, the government is a reflection of the people. If we are responsible for these policies, it is the people who are responsible for supporting them.”

All of the roles include references to other roles, planting seeds for students to show how other groups participated in the crime. For example, in the Business Owners Under Capitalism indictment, students find the following paragraph:

Beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, and more recently with the Immigration Act of 1924, Congress has decreased your access to immigrant labor. With those acts, Congress was more concerned about restricting the immigration of Asians and certain “undesirable” Europeans than with people from south of the United States, like Mexico. But now that the United States is in such hard economic times, the government is suddenly targeting Mexican workers too. You say that you oppose these new policies because Mexican Americans are more loyal, work harder, and do better work than white workers. But those are lies. The real story is that white workers are much more likely to be part of a labor union. Labor unions mean higher wages. And that means lower profits and less control for you. You don’t really care about the lives or well-being of the workers being rounded up and deported; you care only about your profits.

References to the AFL and the Federal Government signal students in the Business Owners group to turn to those indictments for evidence of the guilt of those groups as well. The point here is to encourage students to analyze how injustice actually happens. Too often we think about such matters as simplistic cause and effect — a law was passed, a general gave an order — with everyday human actors removed from the equation. This trial asks students to see the more complex tapestry of human complicity in an enormous injustice like mass deportation, genocide, or global environmental destruction. This is not just an academic exercise. One “habit of mind” we want to nurture in our students is for them to think deeply and expansively about the cause of injustice. Ultimately, their sense of how injustice should be addressed rests on their understanding of what is causing the injustice in the first place.

Once students have carefully read and discussed all the indictments, I ask them to write up their formal defense, which they will deliver the next class period. I encourage them to write collaboratively and to make sure to include a combination of reasons they are not entirely guilty and reasons other groups deserve blame. Some groups decided to place the blame entirely on one group. For example, Julian’s group, the Racist Media, wrote:

We are words on a page. We are voices on the radio. We are protected by the First Amendment to write and say what we want. We do not pass laws. We do not arrest people. These deportations are the fault of the men who wrote the laws and made the arrests: the government.

Other groups decided to allocate the blame broadly. For example, Karen’s group, the Deportees, wrote: “Everyone in this room is to blame for what happened to us. Whether you directly rounded us up or stood by and watched, this is YOUR fault.” Still other groups landed on admitting partial guilt while still placing the bulk of responsibility elsewhere. Grace’s group, the Police and Immigration Agents, wrote: “Yes, we did things that were unconstitutional, but nobody was stopping us. Isn’t that the job of the Federal Government?”

On the day of the trial, I selected some students to be jurors. In one class, I selected five kids who’d been absent the day before. In other classes, I pulled one kid from each group after defenses had been written. In another small class, I had an administrator, an educational assistant, and a couple of students on the jury. It worked in all three configurations. The key here is to have a group who can help surface important information by raising key questions.

In the trial, I played the prosecutor, trying each group, one by one. Pulling key ideas from the written indictment, I delivered a short, dramatic accusation of guilt. For example, to the Media group I said, “You are the ones peddling this poison, infecting the thinking of every person in this room. You dehumanized your neighbors. And for what? To sell papers?” I ended each short indictment with “How do you answer these charges?” — cueing students to deliver their prepared defense to the jury.

After students read their defense, I gave the jury and other groups an opportunity to ask clarifying and challenging questions. Again, the goal here was not to get students to pin guilt on one group, but to get them talking about who played what role in the deportations and why.

Over the course of the trial, students established a thick web of complicity. Yes, the deportations started under President Hoover, but wasn’t he acting as a representative of the people? It was the people’s nativist and racist beliefs that drove policy. Those dangerous ideas, argued the Federal Government group, were circulated and amplified by the media. Not so fast, say the Media group. We did not invent racism; we cover U.S. society, we don’t create it. Perhaps look to major institutions like the AFL. By excluding Mexicans from the largest workers’ organization in the United States, the AFL formalized the social exclusion of Mexican and Mexican American workers, making them an easy target. But the AFL reminded the jury that it was unscrupulous business owners in cahoots with the laissez-faire ideology of the government that created the economic crisis driving the deportation policy in the first place. Business owners scoffed, arguing they did not make nor enforce the laws. It wasn’t business owners who were rounding up people in parks and barrios; that was the police and immigration agents.

After all groups were indicted and defended themselves, I sent the jury out to deliberate in the hallway. I told the jurors that they could find one, some, or all groups guilty. I also gave them the option of placing blame on an unindicted co-conspirator — that is, someone or something not in the trial. While the jury deliberated, I asked the rest of the class to step out of their roles to write, addressing the same question as the jury: Who is to blame?

After 10-15 minutes of deliberation and writing, I brought the jury in to announce their verdict. In one class, the jury found both the Federal Government and Police and Immigration Agents guilty, but “exonerated” everyone else. In the debrief that followed, many kids disagreed with the jury’s verdict. Ross, for example, was dumbfounded that the Business Owners got off scot-free. When I asked him, “So who did you say was to blame?” I was surprised when he said, “I actually didn’t find any of these groups guilty.” He went on to explain that he had placed all the blame on money, persuasively arguing that the desire or need for money drove every single group’s action and immorality. Viola also called for blaming an unindicted conspirator: racism. Grace disagreed: “Racism is an idea and ideas do not deport people.” Joey argued that immigration laws in general should be indicted. He said, “If there were no rules about who gets to be here, there would be no such thing as deportation.” In some ways, the trial is a kind of trick question, asking students to parse out collective guilt into its constituent parts. Though unrealistic, by teasing out the individual strands of complicity, students hopefully become more alert to the ingredients of injustice in their own historical moment, and more likely to act against them.

The lesson closes by focusing on what one wishes there had been more of in the 1930s, what we’re seeing today, and what I hope my students will take part in: resistance. I ask students: So who could have stopped this? What could members of each group have done to interrupt the injustice? Jack said the media could have written stories about Mexican Americans that humanized rather than demonized them. Cassie said that the AFL could have worked with rather than against Mexican laborers. Daniel said that local police could have refused to carry out the raids. When Meredith challenged that idea, arguing they would lose their jobs, Daniel said, “Well, maybe that would be a wake-up call for other people that something was wrong.” By asking students to consider possible acts of resistance to a decades-old episode, I am explicitly attempting to arm students with tools to respond to today’s injustices. President Trump alone does not have the power to terrorize immigrants and their families. For that, it takes the collaboration of Fox News, ICE agents, immigration detention centers, builders and contractors, tech companies, and an electorate primed by racism and capitalism to misplace blame for their own low wages or precarious social positions.

If this is true, then it matters how every single one of us responds.

Arming the students with the history of the deportations of the 1930s requires that it is available, accessible, and widely taught. As a wrap-up for this lesson we learn about Leslie Hiatt and Ana Ramos’ 4th graders in California who, after being introduced to the history of the deportations, became political activists. In her Rethinking Schools article, “How My 4th-grade Class Passed a Law on Teaching Mexican ‘Repatriation,'” Hiatt describes her students’ outrage at finding only one reference to Mexican Americans in their class textbook. The students successfully lobbied the state legislature to pass a law requiring the teaching of the deportations. They also sought a federal apology for the deportations. After reading about these activist 4th graders, my students wondered: “Why don’t we have ethnic studies at our school?” “Who decides what’s in the curriculum?” Through our discussion of each of these important questions, new terrains of resistance were revealed, new opportunities for me to encourage my students to take action in places as near as their own classrooms and as far as Washington, D.C.

I want my students to take what they have learned about deportations of the 1930s and be like Jordon Dyrdahl-Roberts, the Montana Department of Labor worker who quit his job in February, explaining on Twitter, “There were going to be ICE subpoenas for information that would end up being used to hunt down & deport undocumented workers. I refuse to aid in the breaking up of families. I refuse to just ‘follow orders.'” I want my students to be like the more than 100 public defenders who recently walked off the job in New York City to protest ICE arrests in courthouses or like members of the Sanctuary Movement who are devising novel and brave ways to put themselves between ICE agents and their targets. And I want my students to be like those 4th graders in California who demanded they be taught about the deportations of the 1930s, who insisted that history matters, and that it might be the history that is not in the textbooks that matters the most.

For lesson materials, click here.

Ursula Wolfe-Rocca (ursulawolfe@gmail.com) has taught high school social studies since 2000. She is on the editorial board of Rethinking Schools and is the Zinn Education Project organizer/curriculum writer for the 2018-2019 school year.