Preview of Article:

Declassified – Struggle for Existence (We Used to Eat Lunch Together)

Students fight to perform their rewrite of Antigone

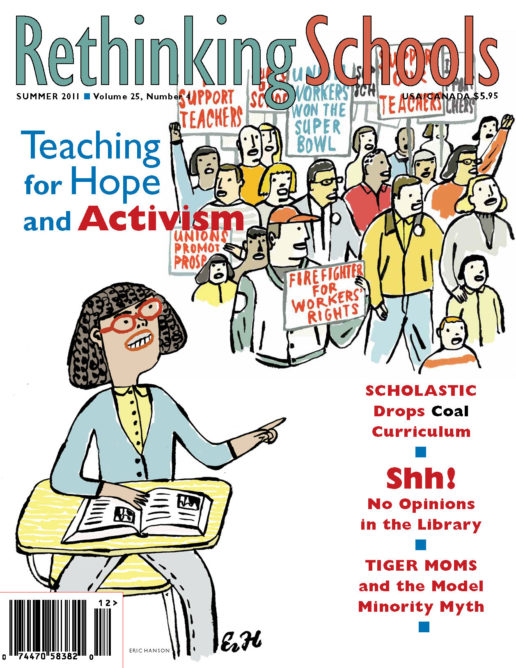

Illustrator: Ethan Heitner

It was a Thursday afternoon just before 4 p.m. I was sitting with my students around an old wooden table in the library of New York City’s Jamaica High School. We were one day away from the scheduled performance of a play the students had written about school “reform” and specifically the planned phaseout of Jamaica High. From the excited talk amongst the students about costume choices and their nervousness about remembering their lines, it was clear they had no idea what was coming. But I was bracing myself to deliver some bad news. Earlier in the day I had received an email from a colleague informing me that the performance was being barred by the students’ principals, who “had issues with the script and are concerned about implications and negative references to the department of education as well as the chancellor and mayor.”

The play, Declassified: Struggle for Existence (We Used to Eat Lunch Together), is based on the classic play Antigone and was written as part of a college-credit elective I teach at Queensborough Community College, geared toward local area high school students. In addition to reading and discussing a translation of the classic Greek text, we also read The Island, a play by John Kani, Winston Ntshona, and Athol Fugard about two political prisoners who stage Antigone to affirm their protest of apartheid South Africa. The exploration of both texts involved discussions of major themes like power, loyalty, and rebellion, as well as an exploration of individual lines that resonated with us.