Creating Bias Detectives, Blowing Up Stereotypes, and Writing Essays that Matter

Illustrator: Adolfo Valle

My high school boyfriend posted a picture of himself with his father and some of our aging back-in-the-day friends in the newly reopened Vista Del Mar, the bar and caf my parents owned in Eureka, California. The Vista had been shuttered for years after my brother sold it, sagging into decay, the neon sign tilting, chin down, like a napping old man, weeds covering the gravel parking lot before new owners saw the potential of a bar by Humboldt Bay. Steve’s photo was accompanied by his remarks about the past menace of the bar: the brawls, the prostitutes, the fishermen and loggers. His post blew up with other snickering remarks from our classmates.

I get it. The Vista was always an easy target. Everything Steve and others said on Facebook was true and yet not the only truth. Certainly not the full truth. To understand the Vista Del Mar, slung against the hips of Humboldt Bay, you’d need to inhale the fish, fresh from the Pacific, scales shining iridescent rainbows in the fog, lighting the dockworkers’ hands, their skin cracking with ice and cold until my mother’s coffee warmed them up; you’d need to know the men who found warmth and camaraderie on the tall red stools of my father’s bar at the end of their shifts. You’d need to learn how women, hair wrapped in bandanas, moved in small bands of laughter after boiling and cracking Dungeness crab all day. You’d need to hear the clang of railroad cars coupling and uncoupling, brakes chasing metal as they pressed against the ties, and smell the steel when the rail workers ordered clam burgers or chicken fried steak for lunch.

When I was growing up, the Vista cast a huge shadow over my life. One I learned to embrace as I came to understand the ways that class played out in my hometown with me as a piece on the checkerboard, moved by small-town prejudice. The post brought back the shame visited on me over the years: the Presbyterian minister who asked my family to stop coming to church because my father owned a “sinful” tavern; the teachers who warned against going down past 2nd Street, where places of ill repute, like my family’s bar, might taint them.

Their comments dismissed Jack Wells, the bartender and co-owner of the Vista, a tall, razor-thin, chain-smoker who read every essay I wrote as if I was Ursula Le Guin, who was the first person I knew, besides my teachers, who graduated college and made me see that possibility for myself. Or the fishing fleet, those who blew in seasonally following schools of fish or those who lived in town, tinkering with old diesel engines, setting crab pots: they taught me the importance of standing together when the fish company lowered prices again and again.

In the years after I left Humboldt County, I taught at Jefferson High School in Portland, Oregon, where rumors of low academic performance and violence shrouded the school, located in the city’s historic Black community. Portland’s white majority failed to see our students’ brilliant writing and academic prowess — they claimed national awards and secured scholarships to top-rated universities.

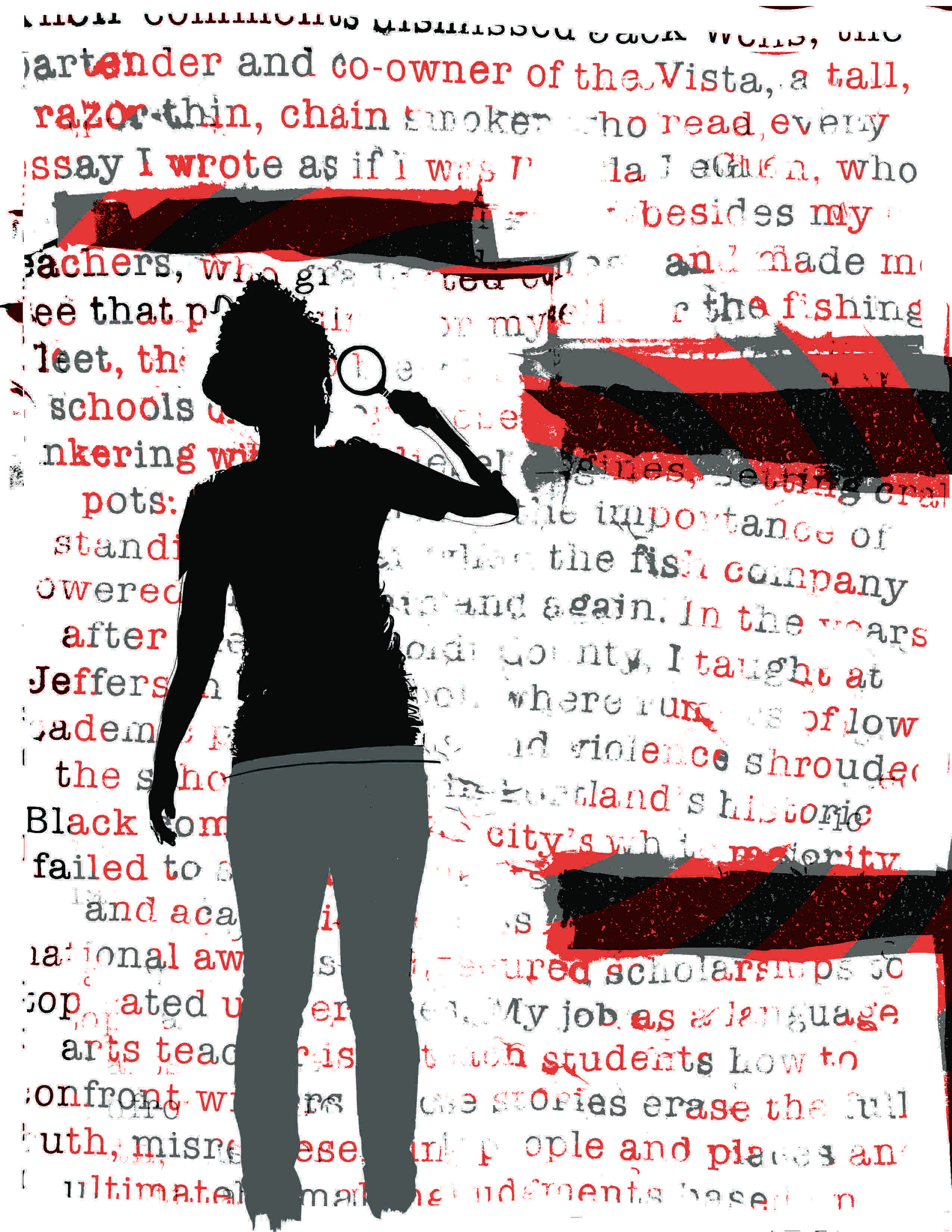

Part of my job as a language arts teacher is to teach students how to confront writers whose stories erase the full truth, misrepresenting people and places and ultimately, making judgments based on inadequate knowledge. Literature is laced with unreliable portrayals of women, people of color, LGBTQ communities, and working-class people. Think of Great Gatsby, Little House on the Prairie, or Heart of Darkness to name just a few. But students also encounter false narratives and partial truths in newspapers, magazines, and presidential speeches.

Part of the work of teaching students to read is teaching them to question not only the written word, but also the author, to develop an internal monitor that pings when a writer slides into convenient phrases or paragraphs that seek to portray a people or world they do not know, and in the telling not only mangle the truth, but also perpetuate stereotypes. Too often, writers normalize the dominant culture as the scale against which other people’s lives are measured. Sometimes this means the author cannot see the beauty or intelligence of other people’s lives because when they line up that vision, they calculate what’s missing or what’s different instead of valuing what is there.

Of course, disrupting habitual stereotypes and bias is not a one-time lesson; it takes concerted effort over years to unlearn attitudes and understandings that normalize whiteness, the English language, middle-class mores, or romantic myths of national greatness. In one deliberate lesson in the art of bias detection, Dianne Leahy — my teacher partner who has granted me the space to co-teach sometimes for a year, a unit, or a lesson — and I paired two articles about the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, one by Timothy Williams, who writes for the New York Times, and one by Willow Pingree, a student at Fort Washakie Charter High School on the reservation. Chelsea Hallam, a talented teacher and writer who teaches at Nixya’awii Community School on the Umatilla Indian Reservation, shared these powerful pieces with me.

Becoming Bias Detectors

Before reading Williams’ “Brutal Crimes Grip an Indian Reservation,” Dianne and I told the 9th-grade students, “You are going to become bias detectives. Whenever you read, you want to think about the writer. Writers bring their worldviews into their writing. That means that they look at events or places and perhaps make judgments. Did anyone make judgments about Jefferson, for example, before you came here? What kinds of things did they say? What did that reveal about their knowledge of Jefferson? What don’t they see that you know?” After a quick summary of the negative remarks Jefferson still receives and the bias those comments reveal, we turned to the readings.

Once we’d anchored the discussion in their common experience about Jefferson, I said, “I want you to read this article critically, to find pieces in the text that make that bias detector go off. I want you to think about what evidence the writer used and why he used those pieces of evidence. Writers can tell the truth, as they see it, but what they don’t see or write about can distort a reader’s understanding. There could be words or phrases or examples that cause you to question the writer. Sometimes it’s not what’s there, but what’s left out.”

There were no set questions for students to answer at the end of the reading, no SQ3R, no level 1, 2, 3 questions. In the same way that teachers create writers by giving them opportunities to write about real issues that they are passionate about, we create critical readers not by giving them specific questions to answer, but by allowing them to build a critical voice, like a Geiger counter, that goes off when they read a section that makes them think, “Wait a minute.” Students need to trust that voice in their head and learn how to use it again and again.

To get us started, I read the first paragraph out loud and asked students to think about what they learned about the reservation and what specific words or phrases led them to that understanding: “At a boys’ basketball game here last month, Wyoming Indian High School, a perennial state power, was trading baskets with a local rival. The players, long-limbed and athletic, are among the area’s undisputed stars, and their games one of its few diversions. On this night, more than 2,500 cheering, stomping people came to watch.”

Students pointed out that basketball was popular — 2,500 fans came to watch a game — and the team was great, but they also noted the language: “one of its few diversions.” Tianna said, “It’s like there’s nothing else going on there, only kids playing games.” Precisely. Sometimes I stop to make a point, like after Tianna’s comment, of how her noticing “few diversions” was an example of using critical literacy, reading with your brain turned on. As students talked, I underlined the projected text on the document camera and wrote their comments in the margin as a visual demonstration of how I wanted them to mark up their pages — allowing their words and observations to become co-teachers in the lesson.

We proceeded through the article, paragraph by paragraph, reading the first page out loud and collectively practicing critique. Students underlined and wrote in the margins. At the beginning of the lesson, a few voices dominated the conversation, but once other students caught on, they felt confident enough to add to the critique. A few students silently copied others’ comments on the article.

In the second paragraph, for example, where Williams lists the ways the recent championship team members died — “killed in a car accident at 19 while intoxicated; murdered in his 20s; struck in the head with an ax not long after graduation” — Mark discussed how the writer focused only on tragedy and death of a few, but didn’t elaborate on the others in the photo whose stories go unnoticed because they didn’t fit the story he wanted to tell about the reservation. Again, a great observation.

Later, students talked about how Williams wrote that residents have to boil their water because of fracking, but he doesn’t ask why this is allowed on the reservation, or how boiling water would rid drinking water of toxic fracking chemicals. Students also questioned why Williams brought up ghosts, “as if this place has always been haunted” but never discussed the origin of the reservation or the loss of land: “The difficulties among Wind River’s population of about 14,000 have become so daunting that many believe that the reservation, shared by the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone Tribes, is haunted — the ghosts of the innocent killed in an 1864 massacre.”

Overall, students concluded that Williams selected stories and statistics to tell a one-sided story about the reservation. As Lenny stated when we asked students to write a summary of their understanding, “The writer makes it seem like it’s the residents’ fault the reservation is like this. Sure those were awful events, but whose fault is that? He didn’t talk about the way the United States pushed Native Americans onto land whites didn’t want until they found resources on it, like the fracking.” In her reflection about the article, Sinde wrote, “The writer wants the reader to think that the reservation and all of the people on it are bad and it’s all their fault. He used words like ‘gloom’ three times to describe the place, brought up ghosts of the past, but never talked about how reservations came to be in the first place.”

Several months later, Dianne and I discussed the impact of this lesson. Dianne noticed that reading and talking back to the New York Times article built students’ confidence in their critical reading skills. Calling out the way Williams used stories and highlighted certain negative aspects, and failed to explore either the history or what was positive about the reservation, clearly demonstrated the ways that racism is perpetuated by a newspaper that many look to as a trusted source of information.

Fort Washakie Student Talks Back

Michael Read, an English teacher at Fort Washakie Charter High School on the Wind River Reservation, asked his students to read and discuss Williams’ article and to respond to it. Willow Pingree, one of Read’s students, wrote a loving piece, “My Home,” addressing all that Williams failed to see about the place he calls home without ever once mentioning Williams’ article, and yet responding to the points Williams raised. His response was published in the New York Times, first as a comment, then Williams encouraged him to write an expanded essay that was published in the online Learning Network.

To begin this section of the lesson, Dianne and I talked about writing, especially public writing, as a way to fight back when someone misrepresents you, your people, or a place you love. “Writing is a tool we use again and again to disrupt discrimination. When someone has the platform and reach of the New York Times and misrepresents you, you can talk back.”

We asked students to read and “raise the bones” of Pingree’s piece: “As we read, we want you to think about how Pingree talks back to the first article. What does he include that Williams left out? What evidence does he use? Examine paragraphs to see how he constructed them to build a different picture of the Wind River Reservation. You will write your own talkback article in the next few days, so we want you to use Pingree’s as a model.” Then we read out loud, Pingree’s opening paragraphs:

The smell of fry bread and burgers, the laughter of friends and family reminiscing about good old times, the sound of music and the sight of people dressed in regalia, dancing inside an arbor while spectators watch from bleachers around the big arena. You’d find all of this at the Annual Eastern Shoshone Indian Days, or the Northern Arapaho Celebration powwow on the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming.

As you walk around the outside of the dance arbor, you’d see crowds of people walking around you, sitting against wooden posts built along the outer rim of the powwow arbor: people sitting around a big circular drum, beating on it together in one rhythm and singing together in harmony. As the singers continue blasting their voices to the sky, the dancers slide and sway to the heartbeat of the people, the powerful sound of the drum. Surrounding them, the rolling hills, the sage brush covering the beautiful prairies, the awe-inspiring view of the towering Wind River Mountains.

This is my home, and it has been the home of my Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho people long before my generation.

Students were quick to point out that Pingree’s article starts with a description of the reservation, and he makes the reader want to be there Ñ the beauty of the setting, the laughter, singing and dancing of his people, and the fry bread! On the document camera, Dianne wrote next to the opening paragraphs, “This is one way you could start your essay.”

As we continued through Pingree’s essay, students noticed that he brought in the history of the reservation that Williams did not discuss, including both the establishment of the reservation and the fact that “Native children were forced to go to boarding schools to learn the Christian way of education. Their long hair, which was a symbol of pride and honor, was cut off and they were prohibited from speaking in the language of their people.” He also addressed the issues of alcoholism and violence Williams discussed in his article by describing the multiple programs on the reservations. He ends with hope — the resurgence of Indigenous language and culture instruction. “As Chief Washakie said: ‘I fought to keep our land, our water, and our hunting grounds. Today, education is the weapon my people will need to protect them.'”

After we finished reading Pingree’s essay, Dianne and I asked the students to make a list of the kinds of evidence they might include in their own writing based on Pingree’s piece. “As we read the article, we ‘raised the bones’ of how he talked back. What are some of the elements he used?” Students noted the opening description, use of history in several ways, and specific examples of programs.

Disrupting Contempt for Our “Homes”

Using Pingree’s piece as a model, we asked students to brainstorm a list that outsiders don’t understand or misunderstand about their lives. I asked students, “What are some commonly held assumptions about a place or an aspect of your life that needs to be problematized or disrupted? We are going to dismantle those assumptions and talk back to the consequences of these remarks. I want you to think of home broadly. Home could be your language, street, school, body, race, country of origin, religion.”

I created three columns on the document camera: “Home,” “What needs to be disrupted,” and “What is missed? Overlooked?” I wrote Jefferson HS in the first column. Then I asked, “Let’s return to Jefferson. What are some assumptions that need to be disrupted about Jefferson?” Students answered, “Dangerous. Not academic,” and they began the litany of misunderstandings that students and teachers have battled for decades. Then we moved to the last column. “OK, so what do you know about Jefferson that people who don’t go to school here miss?” Students again peppered Dianne and me with a ready supply of answers: Friendly students. Supportive teachers. Basketball giants. Nationally recognized dance program. Outstanding Black Student Union and Women’s Empowerment Clubs. Middle College Program where they earn college credit while in high school.

Once we demonstrated the assignment by using Jefferson as a model, we asked students to generate a list from their own lives. Several students catalogued the streets and neighborhoods around Jefferson that have been hit the hardest by gentrification — Albina, Mississippi, Killingsworth — but students also noted their gender or sexual orientation, religion, race, and the apartment buildings they live in, as well as former schools and countries they emigrated from — Somalia and El Salvador. They continued through the other columns, adding what needed to be disrupted about their “home” and what people overlook or miss. Once their charts looked full, we asked them to share in groups of three. “As you listen to others, either ask questions or give them ideas about what to add to help them with their writing. Listen with a pencil or pen in your hand because you want to be specific in your remarks, but their list might also give you ideas.”

Before students started writing their essays, Dianne and I returned them to the bones of Willow Pingree’s model, reminding them that they could describe their home, write about the history, perhaps include people. “There is no one right way to do this. Find your own way, and when you get stuck look back to your chart about what needs to be disrupted or what is missed.”

By the time the last five minutes of the period rolled around, many students had written at least one paragraph. We encouraged a few students to share before class ended to help those who were stuck find a pathway forward.

During the next class period, while students wrote, Dianne and I read over their shoulders and on Google docs, locating paragraphs or sections we wanted students to share so classmates see how others approached the writing. For example, Katy wrote a great descriptive paragraph about her neighbors on Killingsworth Street, Arthur shared a strong paragraph reflecting how gentrification in his neighborhood affected his family, Stella wrote about people’s negative perceptions of her apartment building. In other words, the students’ work-in- progress became the writing “textbook” for this essay.

Patricia Smith: Bumping Up the Language

Because neither Dianne nor I believe that students learn to write better by giving them grammar and punctuation lessons isolated from their writing, we pulled out our favorite writing/grammar text: a Patricia Smith poem. Smith is a National Poetry Slam winner, and her book Blood Dazzler, about Hurricane Katrina, was nominated for a National Book Award. Name an award, and she has either received it or been nominated for it. Watch her perform and you’ll be singing hallelujah before the end of the poem. Her verbs sing. Her metaphors make you see the world in new ways.

So to get students to write more dazzling paragraphs about what people missed about their “home,” we introduced them to Patricia Smith’s poem about the poet Gwendolyn Brooks, “You need to know Chicago if you’re going to learn to miss her.” Although the entire poem is amazing, we focus on a few paragraphs, beginning with the following stanza:

To understand the question, you need to know Chicago . . .

You need to feel the slivers of ice in its breath, ride its wide watery hips, you need to inhale a kielbasa smothered in slippery gold onions while standing on a corner in a neighborhood where no face mirrors your own. You need to know the West Side, the hurting fields, the home of Q Ali, the home of Regie Gibson, the chocolate city burned to its bones in ’68. You need to know how flap-jowled Mayor Daley walled us in, forced us to build our own language and our own castles crafted carefully of dirty dollar bills and free cheese. Every colored girl on those streets had to be a poet, or die. We all scanned the world with Gwen’s huge and hungry eyes.

Before reading Smith’s ode to Gwendolyn Brooks, we told students, “As we read over the poem, mark it up, take notes from this master poet: How does Smith make you see, hear, and taste Chicago?” After reading, we discussed the repetition of “you need to know” and the specific details Smith includes about Chicago — the names, the places, the dizzying specificity that builds the love for a place in the same way that Willow Pingree does in his opening paragraphs. We encouraged them to find some words or phrases from Smith that they love, like “watery hips,” because sometimes borrowing a few words from a writer can help students ignite their prose, get them out of the rut of the worn path of their own language.

After reading and discussing the poem, we told students, “Go back to your essay and find a place that seems good, but not great. Take it up a notch by turning into Patricia Smith. Find some language from her poem to slide into yours, use alliteration, use lists, take a page from her poem and explore outrageous specific details to make your place or people come to life. Get as sassy and outrageous with your language as Patricia Smith does in this poem about Gwendolyn Brooks and Chicago.”

Aisha’s love of Somalia shines through in her opening paragraph as her words lift to life by following poet Smith’s lead:

To understand Somalia, you need to hear the rappelling wings of chickens demanding food. You need to smell the fresh salt against your tongue like a splash of water. You need to see plants coming alive before your eyes and the camel’s thick coat reflecting the sunlight. You need to experience the night falling, the day dwelling in its final hours. You need to hear the Adhan reciting from his heart. You need to feel the heat in the mornings and smell the meat and onions from the sambusa from your mother’s kitchen. You need to learn to say “ha” meaning yes with a nod.

Ayuntu’s piece about Islam cites experiences not only of the beauty and warmth, but also of the times she’s experienced fear:

If you ask me about Islam, I will tell you about the tantalizing smell of fried dough and sambusas during the month of Ramadan, the feeling of tranquility that settles upon me as I go to the mosque with my family to pray taraweeh, the excitement and happiness that overcomes me when another Muslim greets me on the street with “As-salamu alaykum.”

If you ask me about Islam, I will tell you about the surprise and fear I felt when a man whispered “f*ck Mohammed” to me at a Fred Meyer. I’ll tell you about the borderline interrogations that occur at school when people want to ask me about my religion. I will tell you about the anger I feel when other kids say “Allahu Akbar” then pretend to blow stuff up, because if I try to say something about it, they just laugh and walk away.

I’ll tell you about the anxiety I feel when I hear of a new attack somewhere, my mother and I on the edge of our seats, praying he doesn’t have an Arab-sounding name, praying he’s not a Muslim, praying that the words “Allahu Akbar” never came out of his mouth, and having to deal with the hypocrisy of certain people and news, who wouldn’t dare politicize the Las Vegas attack, but gladly will when talking about attacks caused by “radical Islam.”

For some students, these prose, poetic paragraphs launched their essays more fully, accessing their love of place or body or street and helping them gain passion for their writing — moving them beyond assignment and into that pocket where writers find new meaning.

* * *

Years after my family locked the doors of the Vista Del Mar for the final time, I have learned to count the many ways that our culture’s measures are toxic, limited, and damaging. Now I am hungry for my mother’s clam chowder, for the laughter of the women on the docks, but also for the knowledge about the stories of those I wanted to leave behind because I allowed other people’s views of my home to shape my own.

As teachers, we have an obligation to use our classrooms to create authentic lessons rooted in our students’ lives that teach them to read critically, to disrupt incomplete and false narratives about themselves and others, to help them learn to love and appreciate the beauty of rappelling wings of chickens, the camel’s coat reflecting sunlight, or the tranquility of the mosque.

Resources

Williams, Timothy. 2012. “Brutal Crimes Grip an Indian Reservation.” The New York Times. Feb. 2. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/03/us/wind-river-indian-reservation-where-brutality-is-banal.html

Pingree, Willow. 2012. “My Home.” The New York Times Learning Network. Feb. 17. https://learning.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/02/17/guest-post-a-native-american-student-responds-to-a-times-article-about-his-home/

Smith, Patricia. “You need to know Chicago if you are going to miss her.” Modern American Poetry. http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/s_z/p_smith/onbrooks.htm