Preview of Article:

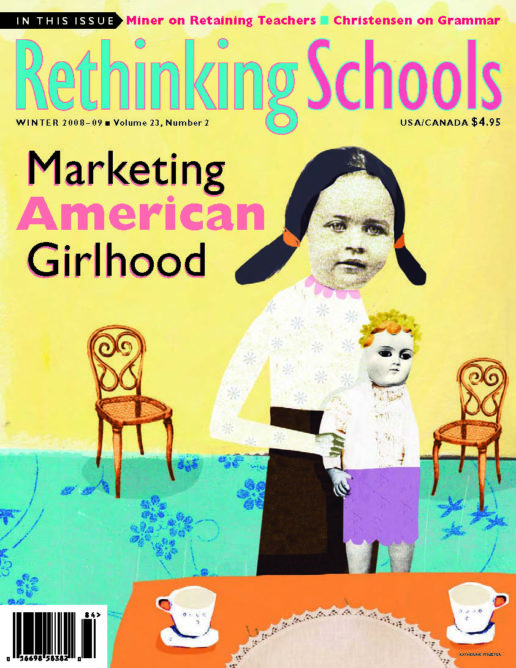

Marketing American Girlhood

Felicity's tilt-top tea table and chairs, $98.00; Addy's trunk, $159.00; Molly's vanity table, $60.00; girls learning about consumption and brand loyalty by the age of 10, priceless.

Illustrator: Katherine Streeter

American Girl, makers of high quality dolls, historical fictions, films, and other products for girls, has cornered the market on how to sell American girlhood to the public. Its popularity came to my attention during my university teaching. I regularly teach an introductory children’s literature course for preservice teachers. With few exceptions, most of the young women in my class enthusiastically remember reading the historical American Girl books and playing with the dolls. After several semesters of hearing about the merits of American Girl from my students, I decided it was time to investigate this cultural phenomenon.

I remember two dolls from my girlhood, Barbie and Crissy, who had hair that you could adjust in length by twisting a knob on her back. These dolls did not fare well; they experienced numerous multilevel falls from bedroom windows and hairdressing appointments during which my sister and I melted each doll’s lovely locks on hot light bulbs. One of Barbie’s feet had been half-gnawed off by a mouse in our attic. Thus, I came to the American Girl materials with a certain distance and ambivalence about dolls.

Nevertheless, I signed up to receive the American Girl catalogs and read the historical fictions. I learned that they are expensive: the Samantha Parkington doll, book, and accessories, for instance, costs $105.00. I made a trek to the American Girl Place, a three-story shop in Chicago. American Girl Place transports the visitor to another world where one can shop for dolls, accessories, books, or child-size versions of American Girl doll clothes; stop by the hair salon to get an American Girl doll a new “do”; make a reservation at the cafe where adults, girls, and their dolls (sometimes dressed in the same outfit) enjoy brunch, lunch, afternoon tea, or dinner; pose for a picture at the photo studio; or watch a movie in the theater.