Cops Don’t Keep Kids Safe at School: The Case Against School Police

Illustrator: Joe Brusky

Before I was taught a single teaching technique, I was taught to fight school shooters.

At the start of the Stanford Teacher Education Program, we took a seat in the library of Columbia Middle School (CMS) in Sunnyvale, California. The school hosted the Stanford Summer Explorations program, an academic enrichment program for middle schoolers where we first dipped our toes into the teaching profession under the guidance of mentor teachers. After a few introductions, CMS staff presented a video titled “Run Hide Defend,” a 2014 production of the Santa Clara County Police Chiefs’ Association, produced in partnership with the Gilroy Unified School District and police departments throughout the county.

A scrawny white teenager enters a school’s administration building, shooting the first man he sees. We cut to a librarian helping a student check out a book. Shots ring in the distance, growing louder as the shooter approaches. The librarian springs into action and directs students out of the library. The video instructs us to “Call 911 when safe,” informing me that it was our job to initially inform the police and other emergency services that there is a school shooter.

“If escape is not feasible, hide and create a stronghold,” the narrator tells us. After creating a barricade, silencing cell phones, and turning off the lights, again we educators are told to call 911 to alert the police.

The narrator assures us: “Police will enter the room when the situation is over.”

We reach the last resort: Defend. The teacher grabs a fire extinguisher. He stands in front of his barricaded students, ready to strike the shooter. The narrator tells us: “Prepare yourself mentally and physically for the possibility of engaging the shooter. Your job is to be the leader, and the first line of defense of your students.”

A handful of officers walk through campus, guns drawn and pointing forward. “Do not make any sudden movements,” the narrator commands. “Remain calm and follow the officers’ commands.” They enter the cafeteria, where students have already disarmed the shooter and piled on top of him. The police scream at everyone to get on the ground, pointing their weapons at multiple students in the room, before arresting the shooter.

Missing from this video are school resource officers (SROs), uniformed police frequently stationed at schools, usually armed. The video does not feature them hunting down the shooter or calling for backup. It does not delineate their responsibilities in the event of a school shooting. They simply are not there.

The lesson was clear: Cops don’t stop school shootings. Staff and students do.

Having taught in Oakland for several years after watching that video, I’ve seen clearly how cycles of poverty, violence, and trauma manifest on my campus. I’ve seen students brutally attack one another. I’ve heard rumors and reports of weapons changing hands and threats of school shootings. And in every single instance, I’ve seen unarmed professionals trained to work with young people leverage the relationships they have with students to de-escalate tense situations and repair harm after violent ones. Never have I seen a situation that would have been better handled by a school resource officer.

The police do not keep kids (or adults) safe at school, whether from school shootings or any lesser offense. Teachers, support staff, and students themselves do.

***

Defenders of SROs often invoke the threat of school shootings. Because even when they concede that SROs should do this and not that, get trained and retrained, unlearn their biases, and better connect with their community, the uniquely American specter of school shootings haunts our discourse, permanently justifying the presence of an armed officer in the case that they could stop a shooter. It’s an end-justifies-the-means argument that casts the police critic as an out-of-touch ideologue who cares more about their radical politics than the safety of our innocent babies. These defenders may have Marched for Our Lives and gun control legislation, but anchoring their support for police in schools is the same infamous logic of Wayne LaPierre, leader of the National Rifle Association: The only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is with a good (cop) with a gun.

This misconception begins with the myth of the “thin blue line.” On one side of the line is a beautiful yet fragile society. On the other side, the forces of depravity and crime. Our “boys in blue” hold that thin line between peace and its enemies. This myth started with the “thin red line,” which originally commemorated the bravery of British redcoats fending off a charge of Russian cavalry in the Crimean War. It was later adapted to American policing, finding its most ardent champion in Los Angeles Police Department chief William H. Parker. He was a vicious racist who described Black people revolting against police brutality in Watts, California, in 1965 as “monkeys in a zoo.” He often invoked the thin blue line in his speeches, and he used his proximity to Hollywood to produce the show Thin Blue Line and control the production of Dragnet, both of which glorified the LAPD.

The assimilation of the “thin blue line” into the American psyche makes it difficult for many to imagine removing the police from any facet of life. Its logic rationalizes the expansion of policing everywhere while opposing its reduction anywhere, lest we surrender civilized territory to the charging cavalry of crime and violence. Those of us who call for eliminating police are bombarded by the eternal what-if: What if you’re robbed? What if there’s a school shooter? What then?

The fact is, cops don’t stop school shootings. While cities have spent a larger share of their budgets on police since 1977, and the percentage of schools with on-campus police has skyrocketed since 1970, school shootings in the United States have increased in frequency. As many of us know, the United States is No. 1, hosting 57 times more school shootings than other industrialized nations combined since 2009. Rutgers professor Matt Mayer told Alex Yablon at the Trace, “We don’t have any rigorous causal evidence that says armed guards reduce school shootings or school violence.” Yablon also cites a 2013 joint study of 160 mass shootings by Texas State University and the FBI, finding that none of the 25 shootings on school campuses in their study was stopped by on-site police or armed guards. Like the Santa Clara County police instructed us in “Run Hide Defend,” most shooters were stopped by unarmed school staff.

Still, defenders of school police may claim that the imagined possibility that they could stop a school shooting justifies their presence. The problem is, it’s not their job. You may remember footage of school resource officer Scot Peterson staying outside while a gunman killed 17 people inside the halls of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida. Although Trump seized on the moment to paint Peterson’s cowardice as an individual failure rather than a function of the system, the gears of police immunity kept turning. A federal judge ruled that Peterson had no constitutional duty to intervene during the rampage.

Though an investigation and public outcry later led to Peterson’s arrest on child neglect charges, this case challenges the long-standing precedent that the police are not required to protect you if you are not in their custody. University of Florida law professor Darren Hutchinson told the New York Times: “Neither the Constitution, nor state law, impose a general duty upon police officers or other governmental officials to protect individual persons from harm — even when they know the harm will occur. Police can watch someone attack you, refuse to intervene, and not violate the Constitution.”

Meanwhile, the police’s voice from “Run Hide Defend” rings in my ear: “Your job is to be the leader, and the first line of defense of your students.”

***

Sometimes defenders of school police recall some near-tragedy about the police finding a knife or gun in a kid’s backpack once upon a time. Again, like school shootings, these arguments depend on the fear of what-if, not the reality of what happens. Comparing schools with and without SROs while controlling for socioeconomic status, juvenile violence researcher Matthew Theriot found only small differences in the rate of arrests of students for drug possession, public intoxication, assault, and weapon possession.

Meanwhile, Theriot found that “having an SRO at school significantly increased the rate of arrests for [disorderly conduct] by more than 100 percent even when controlling for school poverty.” Disorderly conduct’s closest cousin in school discipline parlance is “willful defiance,” a category of misbehavior so notorious for producing huge racial disparities in school suspension that California passed a law restricting schools from suspending or expelling students for it. Theriot’s research suggests that the presence of SROs, especially in poor schools, subjects students to excessive criminal punishment for an offense that we know to produce serious racial discrepancies in mere academic punishment.

And the more students of color a school has, the more likely it is to host an on-campus police officer. When schools increase the numeric frequency with which students of color encounter the police, they increase the likelihood that students’ antics or trauma responses are criminalized. A 2017 study by the Education Week Research Center found that 43 states and the District of Columbia arrest Black students at disproportionately higher rates, and they name higher exposure to school police as a likely cause.

A UCLA study of 2.5 million students in Texas found that “exposure to a three-year federal grant for school police is associated with a 2.5 percent decrease in high school graduation rates and a 4 percent decrease in college enrollment rates.” A Harvard and Columbia University study found that saturating high-crime areas in New York City with police officers “significantly reduced test scores for African American boys, consistent with their greater exposure to policing.” We’ve also known for some time that “first-time arrest during high school nearly doubles the odds of high school dropout, while a court appearance nearly quadruples the odds of dropout,” as Arizona State criminology professor Gary Sweeten found in 2006.

Then there are the endless stories of police violence against children on campus. You may remember the footage of South Carolina SRO Ben Fields body slamming a Black girl in her classroom for refusing to surrender her cell phone and leave her seat. You may have seen photos of young children with disabilities handcuffed at their biceps because their wrists were too small. A lawsuit filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center revealed that school police in Birmingham, Alabama, had used chemical weapons on 300 students on 110 separate occasions at every high school in the city except the one that requires high test scores for admission.

***

SROs like to claim that they help young people develop positive relationships with law enforcement. The National Association of School Resource Officers (NASRO) define their role in terms of the “triad of SRO responsibility”: educator, informal counselor, and law enforcer. If a school district and/or police department requires officers to get special training to become an SRO, they will likely take NASRO’s five-day “Basic SRO Course.” If an SRO were to take every course currently listed on NASRO’s website, they would receive a whopping 18.5 days of instruction, fewer days than the summer school class I taught to students who had failed a semester of world history. But SROs are more likely walking onto school campuses with just one business week of training under their belt, beside their gun, calling themselves qualified to fulfill three massive roles.

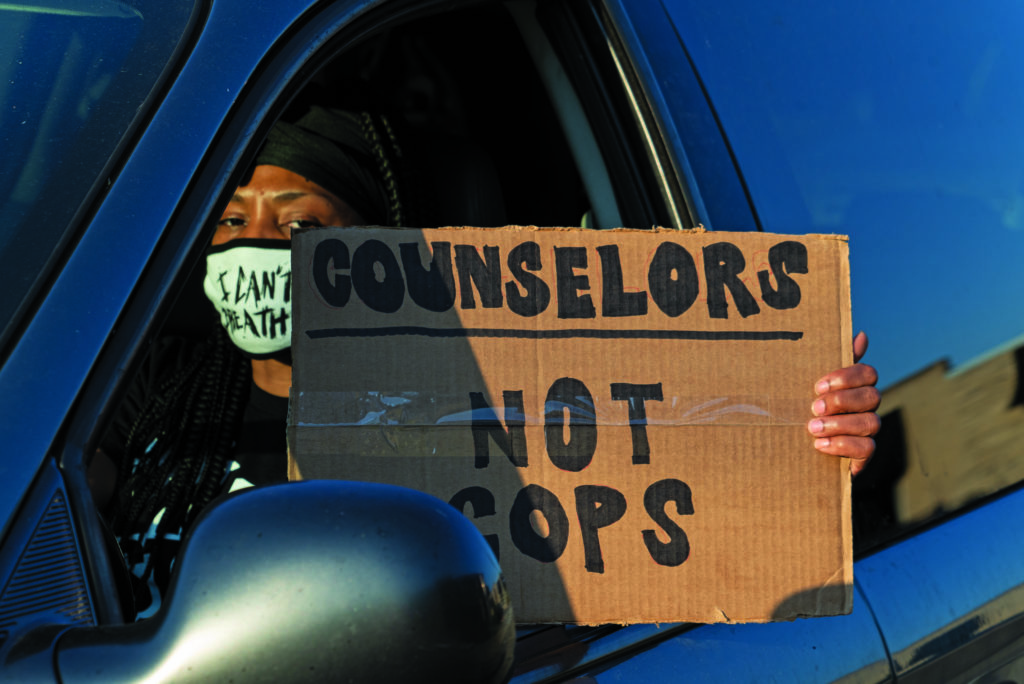

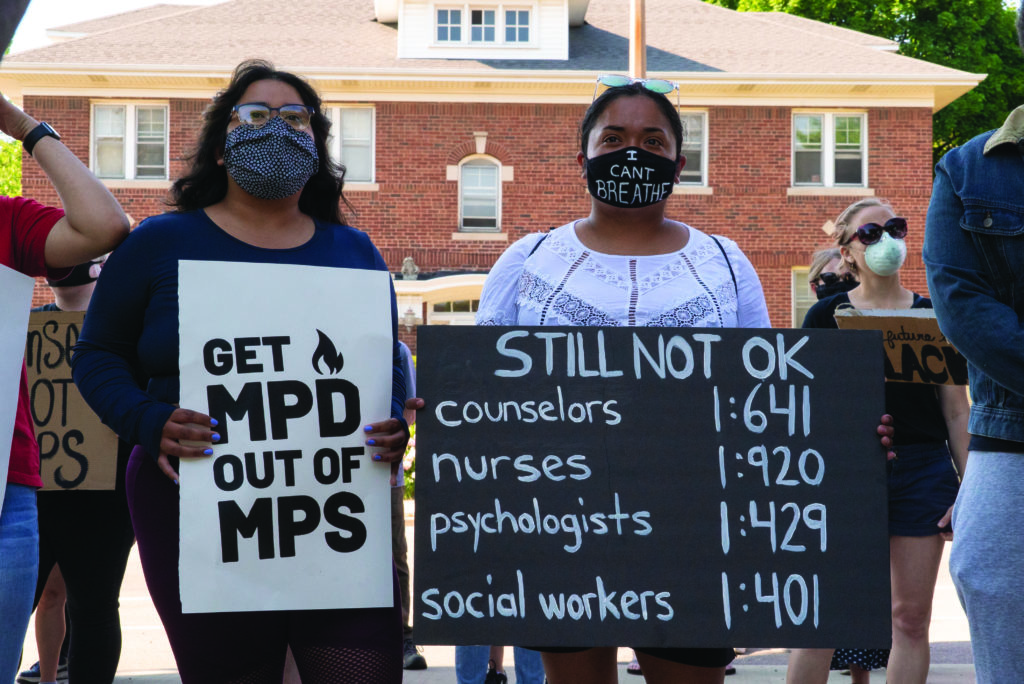

The triad of responsibility begs the question: Why hire someone to be one-third of something called an “informal counselor” when you could hire someone who has earned a bachelor’s degree and completed a year or more of postgraduate study and clinical practice to become an actual counselor? The question is not rhetorical; the answer is money, the permanent austerity schools are expected to accept while police budgets balloon.

NASRO’s description of their role as an educator is even more insulting. They say that SROs regularly teach classes about “bullying, aggression, dating violence, gang violence, driving safety, underage drinking, drinking and driving, drug use, peer pressure, fingerprint evidence, internet safety, search and seizure laws, sex crimes, the rights of victims of crime, and more. . . . And while teachers appreciate the importance of these topics, they often lack the training to provide more than a standard curriculum.”

Teachers and counselors are far more qualified to teach about every single one of these topics than the police. First, to clarify what “teaching” means in this instance, some teachers may schedule time for the police to present to their class on select topics, likely no more than once or twice per year. Teachers and counselors, on the other hand, can build long-lasting relationships with students that allow us to teach and revisit these topics in depth. Health teachers often teach about interpersonal violence, alcohol and drug use, safe sex, and consent. History and government teachers often teach about the rights of the accused and of victims. These teachers should be pushing students to think critically about how fairly the police enforce laws and treat victims. And I can’t imagine who would want the police lecturing their children about domestic violence when even the National Center for Women & Policing admits that “Two studies have found that at least 40 percent of police officer families experience domestic violence, in contrast to 10 percent of families in the general population.”

Students are not registering any SRO triad magic, either. In Alexis Stern and Anthony Petrosino’s review of literature on the topic for WestEd, they found “no conclusive evidence that the presence of school-based law enforcement has a positive effect on students’ perceptions of safety in schools.” Cops are not effective until proven otherwise. They have failed to prove their value in both student outcomes and perceptions. A program this wasteful, ineffective, and harmful should have been slashed years ago.

***

Given the pearl-clutching outrage I’ve seen at the movement to remove police from schools, you’d think that police were some universal feature of U.S. education, a pillar holding up the peace and prosperity of schools. But again, that is the myth of the thin blue line at work. The reality is that in the 2015–2016 academic year, only 42.9 percent of schools had an armed, sworn law enforcement officer on campus at least once a week. Millions of students attend thousands of schools without SROs, and some other combination of professional educators and support staff keep these schools remarkably safe every day. Certainly, students on these campuses “act up,” talk back, skip class, bully one another, fight, conceal weapons, and use drugs. If caught, some of these more serious offenses at schools without SROs may still be reported to local law enforcement.

But we’ll never know how many of these students weren’t arrested because their schools deployed a team of professionals — teachers, paraeducators, counselors, administrators, campus supervisors, coaches, translators, social workers, and others — to respond to their misbehavior with the love, support, and accountability that we are trained to provide. We may not do it perfectly, but we don’t arrest them. And the only way we’ll know how many more kids we can keep out of police custody is if we eliminate the police from our schools entirely, forcing us as educators to do the job our kids depend on us to do: harness their fundamental desire to learn, grow, and be their best.

***

Abolitionist and CUNY geography professor Ruth Wilson Gilmore asks: “What are the conditions under which it is more likely that people will resort to using violence and harm to solve problems? . . . What can we do about it so that there is less harm?” We should ask: What does the research on youth violence actually tell us about what stops it?

Adam Volungis and Katie Goodman’s 2017 literature review on school violence makes it clear: “Overall, there is significant support for school connectedness having a vital role in preventing school violence due to positive school personnel relationships.” They define “school connectedness” as the “perception of being cared for by school personnel, positive relationships within the school climate, and being comfortable to talk to an adult within the school about a problem.” Nowhere in their article do they refer to SROs’ self-proclaimed role of “informal counselor” as a uniquely important resource for schools to utilize. They don’t mention the police at all. They focus on the role of teachers and mental health professionals who have devoted their lives to serving young people and keeping them safe.

Arresting students at school could also divert them from effective anti-violence programs at school. Sandra Jo Wilson and Mark Lipsey’s 2005 meta-analysis of more than 200 research studies on school violence reduction programs found that they were generally effective at reducing common aggressive behaviors in schools (fighting, bullying, and verbal conflict), especially among higher-risk students. They found that many of these programs do not target violent behaviors per se, but instead focus on building school connectedness by helping students develop positive social and communication skills, which in turn reduces violence. They frequently enrolled students who had already committed violent acts at school, acts that could have easily led an SRO to arrest and divert them from these effective programs.

***

There remains an elephant in the room. School police also justify their existence by the number of calls for assistance they receive from school sites. Oakland Unified claimed that its now-disbanded police department received about 2,000 calls per year, although I never found documentation verifying that number. “If you didn’t need us, why would you call?” they may ask. The first rebuttal to this is clear: If police are vested with the responsibility to respond to school emergencies, then they will be called in response to school emergencies. If another institution were instead vested with that responsibility — such as mental health crisis teams, social workers, or special education support staff — then they would receive calls instead of school police. Given how frequently mental health emergencies trigger violent police responses, Yale psychiatrist Dr. Eden Almasude’s warning is salient: “Police involvement in mental health care makes people worse, not better.”

The harder pill to swallow is our own responsibility as educators. We cannot abolish police in schools if educators do not abolish the police in their minds. We must abolish the impulse to escalate conflicts with students, seeking to assert authoritarian power over our students. Teachers must implement trauma-informed de-escalation strategies and build learning environments where students feel empowered to be their best. In “Multiplication Is for White People,” education professor Lisa Delpit describes “warm demanders” as teachers who “expect a great deal of their students, convince them of their own brilliance, and help them to reach their potential in a disciplined environment.” It’s an approach that balances the need for teachers to create welcoming classrooms against the need to challenge students to do the difficult intellectual tasks we know they can do. Warm demanders cherish kids for who they are while pushing them to take responsibility for the harm they cause. They do not rely on the tyrannical exercise of their authority as teachers, secured by the threat of police violence against their students.

Schools need to build well-staffed, multi-tiered systems of restorative justice to handle conflict and repair harm. Teacher and administrator preparation — from credential programs to hiring processes to beginner teacher mentorship programs to professional development to administrative training — must challenge teachers to build safe, anti-racist learning environments that do not rely on the police. Teachers unwilling to unlearn their biases and dismantle the racism of both their classroom management and curricula should not be welcome in schools.

However, these important shifts cannot be preconditions of eliminating police; our students cannot wait for that. Educators not yet committed to police-free schools have little incentive to shift their practice if changes in their material conditions do not demand it. School districts in Minneapolis, Portland, Denver, Oakland, and elsewhere did not wait for all of their teachers and administrators to become abolitionists before taking action to eliminate the police from their schools. These districts and the districts that follow their lead will need to do the difficult work of building school cultures that do not rely on the police.

The video that kicked off my teacher credential program may have made it obvious that cops don’t stop school shootings. But every other lesson I’ve learned about school dynamics and child development made it clear that cops don’t keep kids safe at school at all. They never have and they never will. They stand in the way of those of us who do. We must seize this moment to remove them from schools once and for all.