Confronting Gun Violence Means Confronting Our Legacy of White Male Sovereignty

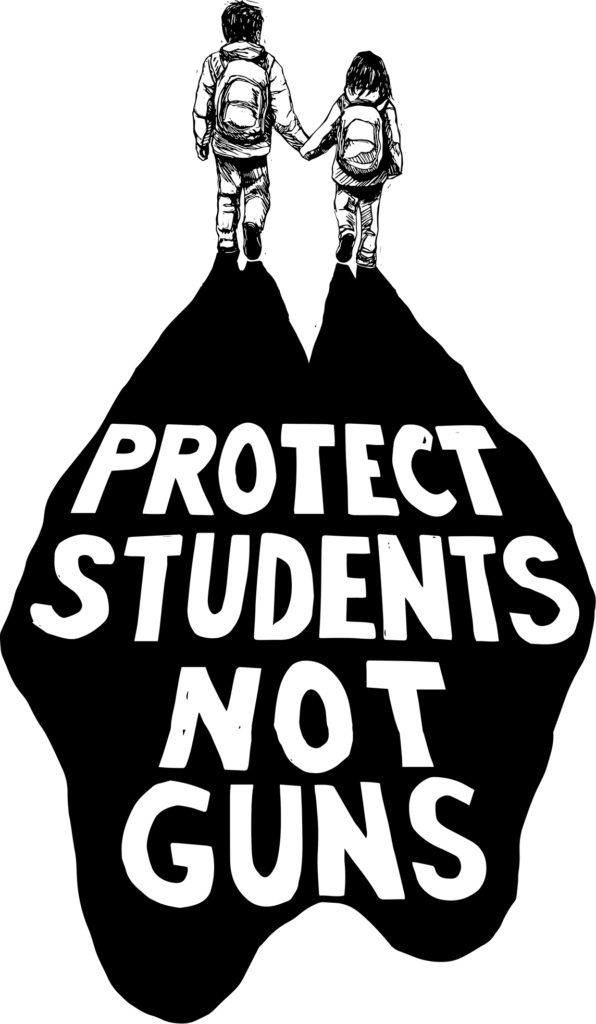

Illustrator: Pete Railand

On May 24, 2022, 19 students and two teachers at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, Texas, were killed in their classroom. Our horror at this mass shooting — the deadliest since the 2012 Sandy Hook massacre — is matched by our horror at how regularly mass shootings occur in our schools. According to Education Week, Uvalde was the 51st school shooting of the 2021–2022 school year.

One year before the Uvalde massacre, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott proudly signed into law seven pieces of gun legislation crafted to, in his words, “ensure that Texas remains a bastion of freedom” — at the same time Texas was banning books and abortion care. The gun legislation included a measure decriminalizing the possession or manufacture of silencers, another that guaranteed “Constitutional Carry” (the right to carry a handgun in public without a license, training, or a background check), and a bill designed to make Texas a “Sanctuary State,” shielding citizens from new federal gun legislation. Abbott’s actions underscored the popularity of guns in Texas, a state home to 8,000 gun dealers and in which 37 percent of adults own guns. But Texas is not an anomaly. There are 393 million civilian-owned guns in the United States. According to the Pew Research Center, in 2020 more than 45,000 Americans died because of gun injuries caused by accidents, suicides, and homicides.

The toll of firearms on children is especially horrific. In 2020, firearms were the leading cause of death among U.S. children through the age of 19 — 4,357 young people. The total equivalent figure in 11 high-income peer countries combined was 153. Both suicide and domestic abuse are often the cause of these deaths, and Black and Latinx children are particularly vulnerable. A study by the organization Everytown for Gun Safety notes that between 2013 and 2019 there were 347 school shootings at K–12 schools, encompassing “gun homicides and assaults, unintentional shootings . . . and gun suicide and self-harm injuries.”

The same politicians who have made it easier to get bullets than birth control have long pushed for increasing police in schools as the answer to school shootings. Yet despite a drastic increase in school police after the shooting at Columbine in 1999, little evidence indicates that police have increased safety, and plenty of evidence shows police presence negatively impacts school communities. In this issue of Rethinking Schools (on p. 12), Mark Warren chronicles how the widespread presence of police in U.S. schools has led to the criminalization of large numbers of disabled students and students of color. The myth that police make schools safer was exposed in Uvalde, as 376 well-funded, well-trained, heavily armed law enforcement officers stood by or aggressively confronted parents during the carnage — even handcuffing some who begged them to enter the building and save their children.

As the murder of Jayland Walker at the hands of Akron, Ohio, police this summer painfully illustrates, while the police failed to prevent death in Uvalde, police regularly cause deaths of Black people (including children) in this country — often with impunity. And although a wide spectrum of political orientations and motivations exist among the 72 million U.S. gun owners, a deep bond remains between gun culture and historic practices of male white supremacy. Scholar and activist Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz documents how colonial settler militias and armed households engaged in assaults on Native American communities. UCLA professor Kelly Lytle Hernández notes that between the 1870s and the 1920s, armed vigilantes lynched almost 500 Mexicans along the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands. Historian Carol Anderson argues that the 2nd Amendment was worded to foster militias in slave states capable of crushing slave revolts and reinforcing the work of slave patrols. She notes that armed terror was a prime tool of white supremacy during Reconstruction and after, with considerable energy devoted to keeping guns out of the hands of Black people. Tellingly, during the 1960s, when the Black Panther Party responded to police brutality in Oakland by utilizing California’s open carry law to protect their community, Ronald Reagan and the state legislature responded by passing legislation to ban open carry.

Recent trends provide a haunting echo of these historic patterns. Sociologist Angela Stroud, who studies how gun violence is legitimated, describes a 2020 demonstration against gun control legislation in Richmond, Virginia, that drew 22,000 mostly white men. The rally was a festival of armed belligerence. Marchers sported camouflage outfits, military tactical gear, and assault-style rifles. Participants included organized militia groups such as the Proud Boys. Infowars’ Alex Jones, who called the Connecticut Sandy Hook Elementary mass shooting a hoax, addressed the crowd from the turret of an armored vehicle. The event foreshadowed the Jan. 6 insurrection through a profusion of Trump placards and signs like “Make Politicians Afraid Again.” Drawing upon scholarship that investigates the intersection of whiteness, masculinity, and guns, Stroud documents how some white men see themselves as patriarchal defenders of dependent women and children against a poor and non-white “criminal class.” Nurtured by the National Rifle Association, the fierce opposition of this group to any meaningful gun legislation has a powerful political impact. Politicians catering to gun worship are sacrificing our children on the altar of what Stroud calls “conceptions of white male sovereignty.”

Working Toward True Safety for Our Students

For many Republican politicians, school safety in the aftermath of the Uvalde, Parkland, Columbine, and scores of other mass shootings depends not on meaningful gun control, but in making schools “hardened targets” by stationing police or military veterans at schoolhouse doors and arming teachers, despite the lack of evidence that such policies help, and much evidence that more guns and police in schools only further harm our most vulnerable students. As teacher Nataliya Braginsky writes in this issue of Rethinking Schools (on p. 10), “In the wake of yet another school shooting, calls to arm teachers are attempting to enlist us as police. But the answer to this moment isn’t becoming cops — and neither is it welcoming more cops into our schools. This moment, which we know will befall us again, calls for reimagining what true safety means, and working with our students to make that a reality.”

What does building true safety entail? One obvious and practical lifesaving measure would be reinstituting the assault weapon ban, in effect between 1994 and 2002, which did indeed lessen homicides due to mass shootings. Other meaningful measures beckon. A 2016 study published in The Lancet medical journal projects that three federal laws could substantially reduce gun homicides: universal background checks for firearms purchases, background checks for ammunition purchases, and effective firearms identification requirements.

But although gun reforms can lessen death, they do not get at the heart of what we mean by safety.

Working toward true safety means addressing the class prejudice, racism, sexism, ableism, homophobia, and hostility that on occasions lead to gun violence, and daily generate verbal and physical harassment in schools. These threats to student safety are exacerbated when schools construe the answer to student misbehavior to be not just police in schools, but also zero tolerance or other harsh discipline regimens. Such measures include strict dress codes or uniforms, random drug tests and sniffing dogs, wand sweeps, and metal detectors. A school that feels like a mini-surveillance state is not a safe space for students. A recent study by researchers at the Social Policy Institute at Washington University and Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Safe and Healthy Schools “suggests schools that tighten security and surveillance in response to shootings or other acts of violence may worsen long-term discipline disparities and academic progress, particularly for Black students.”

The inevitable conflicts of school life are best resolved by teachers and students working together to build strong relationships. Approaches such as social and emotional learning and restorative justice offer promising practices to nurture such relationships. Adequately funded and carefully implemented, such programs can lessen suspensions, expulsions, and incidents of violence, as well as improve test scores and graduation rates. Buttressed by well-qualified mental health professionals, the heart of such programs needs to be school staffs and students who are given the essential resources, guidance, time, and structures needed to actualize their vision. These kinds of initiatives not only reduce conflict in schools, they also can enhance students’ abilities to empathize, to lead, and to engage in dialogue. (In Vol. 29, No. 1 of Rethinking Schools we outline some essential features of effective restorative justice programs.)

As we help students learn to build relationships and community within schools, we also need to provide them a curriculum that helps them confront sources of suffering and danger beyond the schoolhouse door. True safety for students will only become possible when we focus their creativity and moral energy, and our own, on resolving such injustices as unequal health care, homelessness and housing insecurity, poverty, gender and white supremacist violence, ableism, and a burning planet. True safety becomes possible only when we give our students the tools they need to change the world.