Community Building as World Building

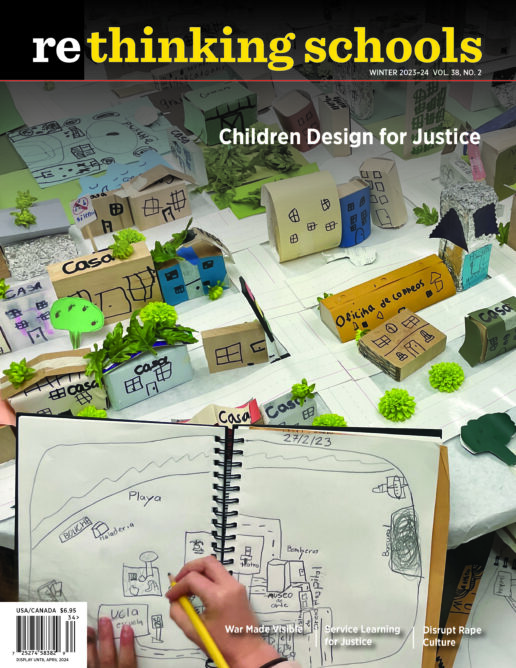

It was a rainy day and a few visitors to our laboratory school huddled outside my classroom under an umbrella, so I invited them in to look at the equity-based community my students had designed. The visitors circled the large table upon which the community was built, taking in the cardboard museums, paper and wood homes, theater, schools, and library — all precisely addressed. “If there are no addresses, the mail won’t get to the right place!” Ella had emphasized in our design process. The visitors noticed miniature aluminum foil bike locking stations next to little benches made from cereal boxes and carefully placed fox crossing and handicap access signs. Eight-year-old Cal eagerly explained:

We have green roofs and white streets to keep the community cool and healthy for people, plants, and “aminals.” Also, this is the plaza central [central plaza] and we have a fountain that says “amor” [love] because that is so important in our community. It has to be at the center. We don’t have police or money but instead we have a farm, a farmer’s market, a free metro underneath the community, free buses, and there is a beach with a lifeguard station and aquarium. For fun, you can bowl across the street from a home for old people or you can eat ice cream and play in the park or in the mountains.

One visitor knelt down to ask, “How did you come up with the names of the streets in your community?”

“Well, the names are all about our values,” Cal expounded. Some of the names were Avenida valiente, Calle de la naturaleza y paz, Avenida de arcoíris, Calle de la amistad, and Calle de esperanza [Brave Avenue, Nature and Peace Street, Rainbow Avenue, Friendship Street, and Hope Street].

I work in a multi-age, Spanish dual language program at UCLA Lab School, part of UCLA’s School of Education & Information Studies. Our three-teacher teaching team works across two classrooms connected by a shared art-making space that allows children and teachers to work collaboratively, and which housed our equity-based community. As a laboratory school, our student population reflects the racial and ethnic diversity and neurodiversity of the children in California; students come from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds. We honor the rich language practices of the multilingual children in our classrooms. We transcribe and reflect on the talking curriculum at our school. Many conversations in this article have been translated from an array of Spanish and English conversations. In our classroom we encourage students to use their full linguistic repertoires and honor children’s home language practices.

Our school has a history of democratic learning and activism. We invest in joyful learning experiences even as we grapple with the climate crisis, racial injustice, gendered violence, ableism, and many other societal issues. Pain breeds possibility.

Like other educators, at the beginning of each academic year, our teaching team explores ways to build community with students. Guided by both the NGSS K–2 engineering standards and the Learning for Justice social justice standards, we posed this question to our students in our first trimester of school: How can we design a community in which everyone gets what they need?

We expected the open-ended question to activate the children’s imaginations as they designed in the pursuit of justice and joy. Engineering and activism in elementary school are inextricably connected.

We didn’t know where this community investigation would go or how long the process would take. As we teach, we transcribe what kids say, document their work, and reflect on children’s thinking and interactions. We place our trust in children’s sense of wonder.

Needs and Wants

The year, like other school years, began with morning meetings, socio-emotional lessons, and many read-alouds about equity and communities. These read-alouds included books that describe community helpers and collective care in action, such as Quinito’s Neighborhood (El vecindario de Quinito) and Thank You, Omu! (¡Gracias, Omu!). We also read A Chair for My Mother (Un sillón para mi mamá), which tells the story of a fire, one family’s loss of many belongings, and the radical support a community can offer. The children had rich discussions about why this particular family needed a chair and how the community helped.

One morning, my colleague Maestra Lozano asked table groups to sort cutout objects into categories of “needs” and “wants.” The objects included bicycles, toys, water, a car, a home, pizza, a soccer ball, pets, clothing, shoes, and vegetables. The children could also draw or write down other “needs” and “wants.” Predictably, children identified vegetables and water as something we all need to stay healthy. But some groups immediately began placing certain objects in the middle of the visible or invisible lines they had drawn between “needs” and “wants.” Avery reasoned “Unas personas son blind or sick y necesitan las mascotas para caminar y hacer cosas.” [Some people are blind or sick and need pets to walk and do things.] Other children agreed that a “want” for one person could be a “need” for another. Some children already understood that certain bodies had different needs. A student who is a twin shared: “Mi hermana [My sister] needs toys because at night she has nightmares. Si la mamá o el papá [If our mom or dad] goes on vacation she needs toys to feel better.”

In response to students’ ideas about bodies having different needs, we read Bodies Are Cool. The text and vibrant illustrations begged the question “How can we design a community in which all bodies (young, old, small, large, disabled . . . ) get what they need?” To address the children’s ideas about safety and our responsibility to keep each other safe, we began to explore community helpers and their responsibilities.

Community Helpers

Now that children had more concrete ideas about needs and wants, the next step was to figure out who would care for those needs and wants in our community. Many elementary school curricula call members of a community “community helpers.”

Initially, our teaching team facilitated a whole-class conversation about the roles of community helpers — community helpers kept people safe or healthy, had different responsibilities, and some inspired us. We used a graphic organizer to generate a list of community helpers.

Later, we asked children in groups to match pictures of helpers to businesses and public services and then choose one or two community helpers and describe or draw how they help their communities. During our whole-class discussion that followed, students easily explained how a person who collected trash helped the community to stay healthy and safe. There was a heated discussion about whether or not a judge’s responsibility was “to find someone guilty” or to figure out how to help people when there are “different perspectives” and feelings have “escalated.”

Kids had another conversation about the police officer. A police officer was included in ¡Gracias, Omu!, one of our read-alouds. One child said the police help keep people safe. When I asked how, he looked at me blankly. Fortunately, we weren’t aware of students having firsthand experiences with the police. Serene said, “We won’t have crimes in our community because everyone is going to have what they need.”

“Plus, the police only come after something bad happens,” Luka added. I tried to summarize: “What I’m hearing is that some people believe ‘crime’ only happens when everyone isn’t getting what they need. Other people are saying police don’t prevent crime — they might show up after a crime occurs.” We are in an era of the streets being filled with people working to defund, even abolish the police, so we didn’t want to ignore these student ideas.

Our teaching team needed to respond to the concepts of violence, greed, and who is “protected and served” in a community. So we thought about how to address some of the ideas that emerged as children made sense of community helpers and their responsibilities.

Over the course of the next week, we read Hay clases sociales [There Are Social Classes]. The book is part of a political series published for children by Equipo Plantel in the late ’70s and, sadly, socioeconomic inequalities highlighted in the book are still as entrenched as ever.

While reading, Lucía wondered: “Can you be stuck in a cage of being not rich?” She pointed at an illustration of happy characters behind a fence of wealth that was impossible to enter and out of which no one wanted to exit. In the illustration, physically smaller and less wealthy people tried to pry their way through the fence of wealth or climb to the other side.

“Yes, certain people are unfairly caught in a cycle of incarceration,” I responded. “That means they can go to prison — and some of those people aren’t able to leave even if their crimes were nonviolent.” Sienna tilted her head and I could see that students needed help understanding nonviolent crime. I asked students to “imagine a mother, father, uncle, aunt, or grandparent stealing food for a hungry child or not paying for the bus to school or to work because they couldn’t afford it.” Benji sat up straight with his palms out, rejecting the imagined scenario: “That is too sad.” I explained these were examples of nonviolent crimes. I cited the American Civil Liberties Union campaign against extreme sentences for nonviolent crimes: “For 3,278 people [as of 2012], it was nonviolent offenses like stealing a $159 jacket . . . [that put them in prison for life without parole]. Many of them were struggling with mental illness . . . or financial desperation when they committed their crimes. None of them will ever come home to their parents and children.” Serene’s eyes searched the room and she said, “I think people need help or therapy, not police.” Serene would later create the therapist’s office in our equity-based community.

Henry was also thinking deeply about safety, which led to another conversation:

Henry: Ningún país y ninguna comunidad es seguro para todos. Es difícil tener todas tus necesidades. [No country or community is safe for everyone. It is hard to have all of your needs.]

Diego: Yo sé porqué los países tienen guerras. Es que los líderes de unos países son egoístas y piensan que “necesitan” lo que tienen otro país. Mandan a los soldados a otros países para quitar las cosas y otros soldados protegen las cosas. [I know the reason countries have wars. The leaders of some countries are selfish and think they “need” what the other country has. They send soldiers to other countries to take things and other soldiers protect things.]

Martina: Los refugiados tienen que come to our country y nuestra comunidad but sometimes we don’t let them. ¡Eso es exclusión! [The refugees have to come to our country and our community but sometimes we don’t let them. That’s exclusion!]

City Planning

At this point, the children were ready to begin city planning. We posed our guiding question again: How can we design a community in which everyone gets what they need?

To scaffold their initial two-dimensional designs, we provided groups of children with a large poster board and the same cutouts of businesses and social services they’d used before with the addition of new buildings and social services that emerged from children’s conversations. The cutouts gave all groups a point of entry. We clarified that students could omit cutouts and add drawings of roads, businesses, and other features they wished to include in a community. Some groups added a lot of their own drawings while other groups mostly used the cutouts.

As children worked, I overheard groups pointing to their designs and talking:

Kaylee: Creo que la cosa más importante para nuestra comunidad es tener plantas. Los árboles limpian el aire y son bonitos. Animales pueden vivir porque los árboles. [I believe the most important thing for our community is to have plants. Trees clean air and are beautiful. Animals can live because of trees.]

Isabel: En nuestra comunidad pusimos el parque con árboles en el centro para que todos puedan llegar y jugar. No tienes que manejar por muuuuucho tiempo. [In our community we put the park with trees in the center so that everyone can come and play. You don’t have to drive for a looooong time.]

Kids were already thinking about the environment, more-than-human community members, and transportation. Our teaching team encouraged children to visit other groups to facilitate the cross-pollination of children’s ideas. We could see children adding tunnels and overpasses for animals to access food sources while still allowing humans to travel within the communities. Other children were making sure there were enough trees for shade, nests, and “good oxygen.”

Another group grappled with the location of businesses and social services with a clear concern for access, equity, and safety:

Cal: The mansion should be the farthest away in our community because they already have everything they need. They should have to drive farther than the people in other homes.

Matthew: La fábrica [The factory] should be far but not too far para que puedan tener cosas pero [so that they can have things but] not the bad stuff from the factory.

Giuli: Las torres eléctricas y el basural tienen que estar lejos de la comunidad. La escuela y el parque deben de estar juntos pero no cerca de una calle grande porque es peligroso. [The electrical towers and dump have to be far from the community. The school and park should be next to each other but not near a big street because that is dangerous.]

Once groups completed a draft, we looked closely at each community and talked about how the designs helped everyone get what they needed. Jack looked at a group’s model and noted, “Everything is around the center green area. What if we had even more trees and bigger parks so you can easily walk in the shade? People need to be comfortable and cool.” Teaching and learning shifts for us as we spend time honoring children’s “what ifs.” Making space for these “what ifs” helps us plan for what’s next. “Jack, that is important!” I agreed. “Remember when we had a few school days shortened at the beginning of our school year because of extreme heat and no air conditioning? So keeping cool is a big concern for you all.” Kids nodded and LilyMaya melodramatically fainted with her hand to her head. That week, my co-teacher Maestra Villalta shared videos and articles related to the urban heat island effect, painting urban streets white and adding green roofs to address Jack’s wondering.

To transition to revision of their two-dimensional poster board models, we directed children’s attention to equitable activities. Which activities might we include in an equity-based community? Some children understood that not everyone would be able to afford the most expensive activities, like skiing. Jacob had a brilliant idea that gave rise to new ones:

Jacob: I don’t think we need bancos en nuestra comunidad [banks in our community] because we don’t need dinero [money]. Todos simplemente [All simply] are going to receive what they need.

Serene: Well . . . what would be your reward for hard work?

Ella: You would go home and feel good about yourself.

Martina: Your reward would be going home and taking a nice nap.

Luke argued that taxes, and in effect money, were good because they paid for parks and libraries. But in the end, children agreed that everyone would care for the resources in the community and work together to help the community without actually having money. Interestingly, the children had excluded police and banks from all of their initial models.

Revising Two-Dimensional Drafts

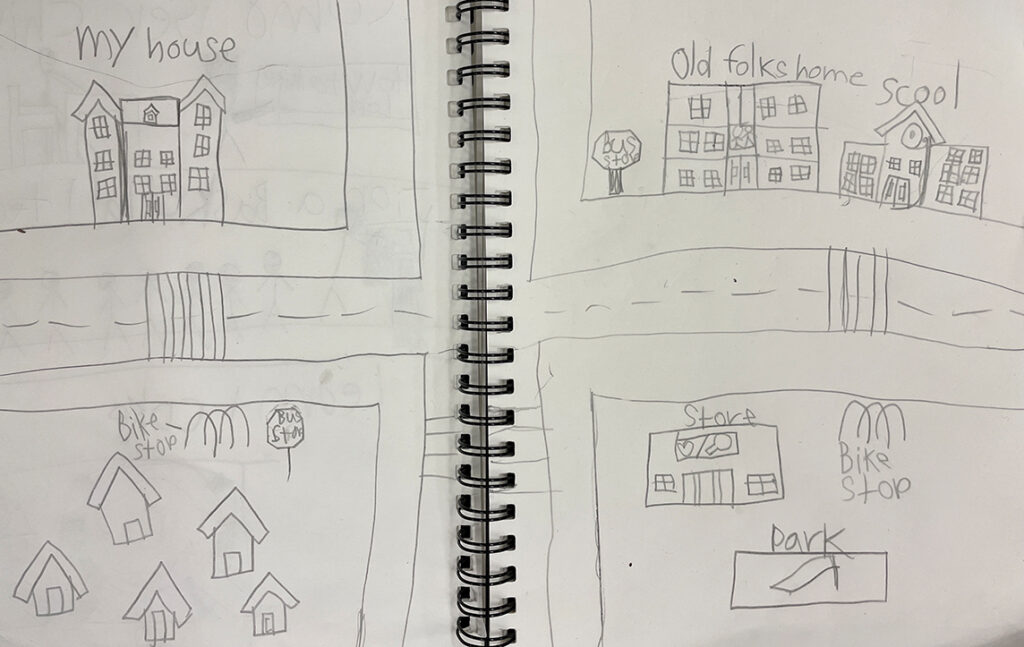

Individually, students drew smaller second drafts of the community in their sketchbooks. During this time, I asked the children to pause so we could zoom in on some of their ideas. Luke had included an “old folks home,” which sparked a conversation about access. Shane looked closely at Luke’s draft and explained to the rest of the class: “I take the bus and it’s a looooong walk from the school to the bus. It would be good to have stops close to the school. This looks like a casa para personas [house for people] who are old and need nurses to help them. They should have a bus stop close to their casas para que [houses so] they can do things.”

Children immediately began incorporating more bike locking stations, bus stops, and even handicap access signs into their second drafts. We re-read Bodies Are Cool and We Move Together, a book about disability justice, ableism, and intersectional activism. The books helped us think about what types of bodies would get their needs met in our community. “I think I know why some people need bigger or littler houses or streets,” Jojo shared. “Sometimes people need more space if they have a wheelchair or if they are pregnant so they can get to places. Everyone deserves to go or ride just like they like to.”

Values-Based Building

Before splitting into groups to start three-dimensional building, I asked the children to make group illustrations of the values they wanted to remember while creating their equity-based community. They illustrated the words love, help, trust, curiosity, honoring differences, hope, inclusion, inspiration, justice, nature, patience, peace, and power. These values helped the children name streets and make decisions about what might be important for meeting everyone’s needs, and what to remember as we organized the community.

Then children chose whether they would work on businesses and social services, transportation, or homes. Two children were “city planning leaders” who reminded everyone about the scale lessons we had learned in mathematics (about reasonably sized buildings and objects) and our goal to create an equitable community. We reminded the children they could use any of the materials available in our atelier — wooden blocks, cardboard boxes, paper, markers, scissors, tape, glue guns, paint swatches, tin foil, etc. — as well as continue to draw in their sketchbooks.

As children began their work, Ella’s group made a careful communal list with oversized checkmark boxes of all the businesses that needed to be designed before they began building. With a Sharpie pen flourish, they steadily checked off completed items on their list. Meanwhile Laurita’s group had a more chaotic approach as they worked on social services. Laurita searched in cardboard boxes, under tables, and in bookcases for buildings that she thought may have already been completed. She stressed to her group the important lesson she was learning about pre-planning and keeping track of completed work and work that still had to be done. The learning was messy and joyful and enduring.

After aesthetic disagreements, permanent marker mishaps, and one glue gun burn, many disparate pieces of a community — buses, a plane, homes, a pet store, a theater — all found their way onto the large round table upon which the community would be assembled. One day, I was surprised to see an ocean permanently glued to the edge of the community even as kids weren’t yet sure how to organize all of the other components.

Just as we had done with the first and second drafts of our two-dimensional models, it was now time to revise our thinking and refocus on our guiding question. We asked half of our students to gather around the large table strewn with our community building blocks. We wondered aloud: “How will community members get to the places they need to go in the community? Where will all these pieces that you’ve built go so that everyone gets what they need?”

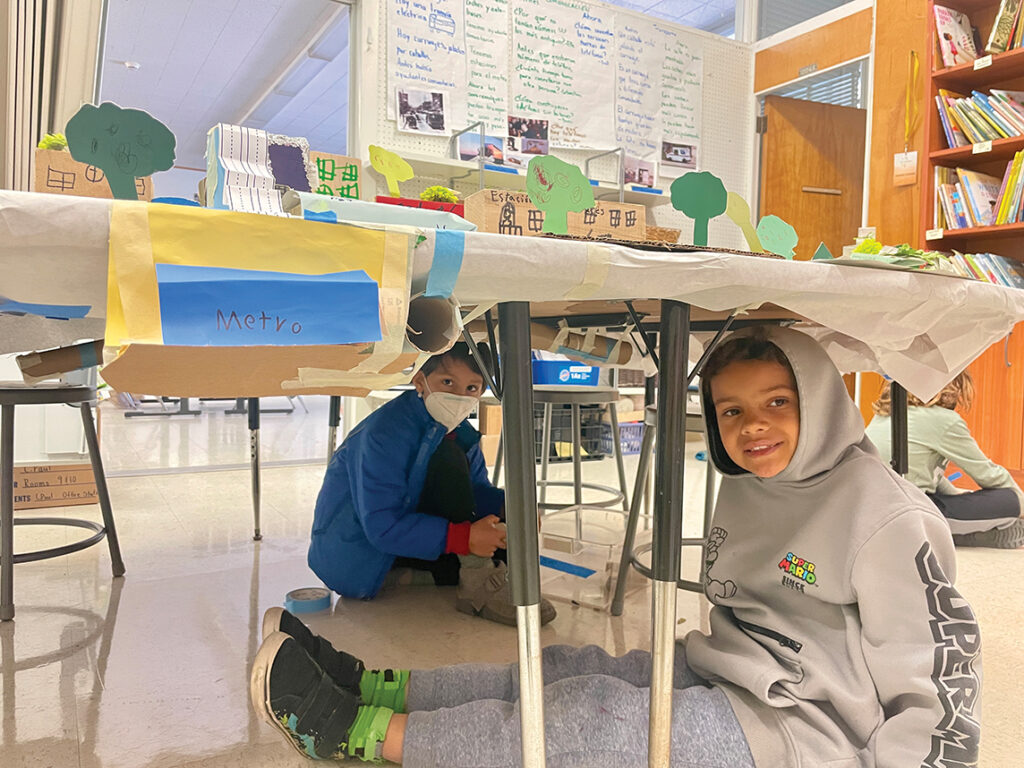

In groups, students began playing with placement of different businesses and social services. They thought, moved parts around, took another look, walked around the table, and tried to persuade peers that their placement of each object would be best for the majority of community members. Some children wondered how people would travel around. We realized an underground metro was under construction when Alexa noticed Luke and Sebastian under the table. She thought they were hurt and quickly called for help! They were OK; Luke and Sebastian were simply busy designing a public transportation system to connect people to the beach, school, and a plaza central [central plaza] that hadn’t yet been assembled.

Other students decided we needed stop signs, handicap access signs, and signs for animal crossing to keep everyone safe. After consulting plans in their sketchbooks, children realized we still had to make the bike locking stations and bus benches included in our drafts. What about the green roofs and plants to keep the community beautiful and healthy?

Again, we helped students form groups to tackle the work that still needed doing. One group worked on street signs, another group worked on plants, and another on bus benches and bike locking stations since the children had decided that cars weren’t needed in a walkable city with free public transportation.

Revision as “Ethically Reimagining”

As children moved around the pieces of the community they had built, new ideas surfaced. “Why don’t we have lights in the streets? Las personas tienen que ver en la noche.” [People have to see at night.] “Necesitamos un lifeguard station para los bebés que no nadan.” [We need a lifeguard station for the babies that don’t swim.] “Necesitamos un parque y las cosas importantes en el centro [We need a park and important things in the center] so people could hang out.”

Ms. Peters, whose class was embarking on a different design challenge involving a community of fantastical animals, got wind of the work in our classroom. We invited her younger students to visit. Their questions and feedback gave our students an opportunity to solidify their thinking and explain their choices, while also revealing that some components of the community were missing. When children explained we had no police because everyone would get what they need, younger kids asked about what happened if people had problems. The idea of a court emerged as a place where problems could get sorted out. After the visit, a court and lawyer’s office were added. Our students also explained to the younger children how people and animals could easily and safely walk around. While explaining how to walk to and from the school and the plaza central [central plaza], the usefulness of street names became evident for navigation and for the post office to easily deliver mail.

Older students also visited our community before it was unveiled to students’ families. The older students talked about how communities are always changing and asked if we had considered solar power. Only one factory had a single solar panel. These older visitors asked questions that offered younger students opportunities to explain the decisions they’d made and articulate their vision of equity. Our students stood firm on no police in the community and explained how unfair incarceration could be and how sad it was to “separate people from their families and community.”

After these visits, the students made final revisions to their design before we invited their families and other children to view their “Equi-munidad.” Jacob invented this portmanteau as a perfect name for the community and the other children embraced it.

* * *

Kiese Laymon talks about “revision as a dynamic practice of revisitation . . . ethically reimagining.” My colleagues and I want our students to understand what the older student visitors shared: “Communities are always changing.” We want students to know that as the world keeps changing, they will constantly make choices and take action in response. We hope our students respond to new information by revisiting old ideas to make informed, we-based decisions. We-based decisions are world building.

There are so many ways that we will be better teachers each year by making small revisions in our practice. We hope we can all, educators and non-educators, ask ourselves: How can we design communities in which everyone gets what they need? At the beginning of this learning experience, 6-year old Cecil thought about all of the members of a community and earnestly declared: “Cada persona tiene una gran responsabilidad.” [Each person has a great responsibility.] The truth of his words have stuck with us. What will we do with this beautiful burden and gift?

PICTURE BOOKS

Cumpiano, Ina. 2009. Quinito’s Neighborhood / El vecindario de Quinito. Lee & Low Books.

Equipo Plantel and Marta Pina. 2015. Cómo puede ser la democracia. Media Vaca.

Equipo Plantel and Joan Negrescolor. 2015. Hay clases sociales. Media Vaca.

Feder, Tyler. 2021. Los cuerpos son geniales (Bodies Are Cool). Rocky Pond Books.

Fritsch, Kelly and Anne McGuire. 2021. We Move Together. AK Press.

Gravel, Elise. 2020. ¿Qué es un refugiado? Anaya.

Kaba, Mariame. 2019. Missing Daddy. Haymarket Books.

Mora, Oge. 2020. ¡Gracias, Omu! (Thank You, Omu!). Little, Brown Books for Young Readers.

Petrus, Junauda. 2023. Can We Please Give the Police Department to the Grandmothers? Dutton Books for Young Readers.

Williams, Vera. 2007. Un sillón para mi mamá (A Chair for My Mother). HarperCollins Español.

OTHER RESOURCES

American Civil Liberties Union. 2013. “A Living Death: Sentenced to Die Behind Bars for What?” ACLU Foundation.

Aterciopelados and Bomba Estéreo. 2022. “Síganme los buenos.” Entre Casa Colombia SAS.