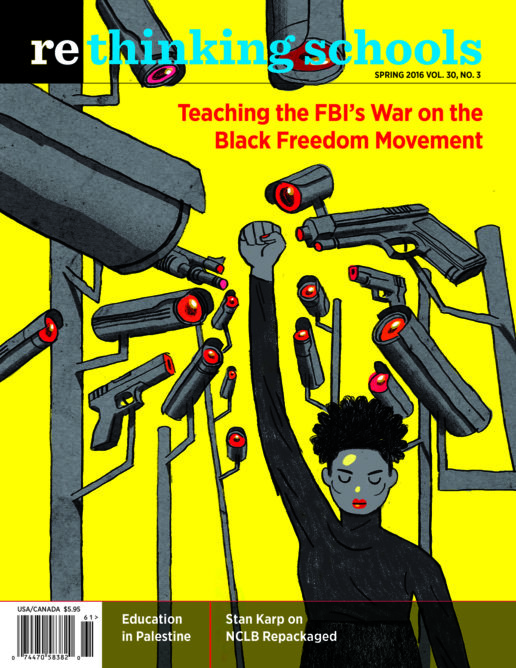

COINTELPRO: Teaching the FBI’s War on the Black Freedom Movement

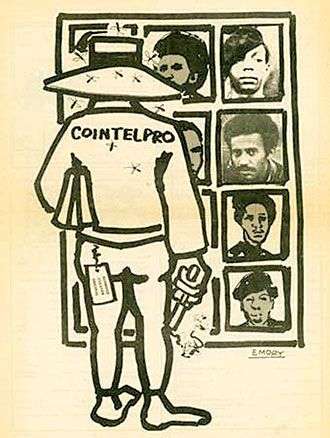

Illustrator: Emory Douglas

Student-selected and student-run current events discussions are a daily ingredient of my high school social studies classes. The first 20 minutes of every 90-minute class period, we read an excerpt from a recent newspaper article and discuss its significance. In the last few years, the discussions have been dominated by names that have piled up with sickening frequency: Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Walter Scott, Freddie Gray, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland. My students, mostly Asian American and white, live in Lake Oswego, one of the wealthiest cities in Oregon and a community that benefits from mostly positive relationships with police. They struggle to understand a society that continues to allow Black lives to die at the hands of law enforcement.

This year, student attention has turned to how activists are responding to the racism in the criminal justice system, particularly the Black Lives Matter movement. In November 2015, a student brought in an Oregonian article, “Black Lives Matter: Oregon Justice Department Searched Social Media Hashtags.” The article detailed the department’s digital surveillance of people solely on the basis of their use of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag. My students thoughtfully discussed and debated whether tying #BlackLivesMatter to potential threats to police (the premise of the surveillance program) was justifiable, with most students agreeing with the Urban League and the American Civil Liberties Union that the U.S. Department of Justice acted improperly and potentially unlawfully.

But what was not noted in the Oregonian article was the historical resonance of this story, which recalls the ugly, often illegal, treatment of Black activists by the U.S. justice system during an earlier era of our history.

My students had little way of knowing about this story behind the story because mainstream textbooks almost entirely ignore COINTELPRO, the FBI’s counterintelligence program of the 1960s and ’70s that targeted a wide range of activists, including the Black freedom movement.

COINTELPRO offers me, as a teacher of classes on government, a treasure trove of opportunities to illustrate key concepts, including the rule of law, civil liberties, social protest, and due process, yet it is completely absent from my school’s government book, Magruder’s American Government (Pearson).

One of the options for U.S. history teachers in my school district is American Odyssey (McGraw Hill). In a section titled “The Movement Appraised,” the book sums up the end of the Civil Rights Movement:

Without strong leadership in the years following King’s death, the civil rights movement floundered. Middle-class Americans, both African American and white, tired of the violence and the struggle. The war in Vietnam and crime in the streets at home became the new issue at the forefront of the nation’s consciousness.

Here we find a slew of problematic assertions about the Civil Rights Movement, plus a notable absence. Nowhere does American Odyssey note that, in addition to King’s death and Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement also had to contend with a declaration of war made against it by agencies of its own government.

American Odyssey is not alone in its omission. American Journey (Pearson), another U.S. history textbook used in my school, also ignores COINTELPRO.

The only textbook in my district that does mention COINTELPRO is America: A Concise History (St. Martin’s), a college-level text used to teach AP history classes. Its summary and analysis takes exactly one sentence: “In the late 1960s SDS and other antiwar groups fell victim to police harassment, and Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and CIA agents infiltrated and disrupted radical organizations.” Without context, without emphasis, without a real-life illustration of what “harassment,” “infiltrated,” and “disrupted” actually meant in the lives of those targeted, this sentence is suffocated into meaninglessness.

Why do textbook writers and publishers leave out this crucial episode in U.S. history? Perhaps they take their cues from the FBI itself. According to the FBI website:

The FBI began COINTELPRO—short for Counterintelligence Program—in 1956 to disrupt the activities of the Communist Party of the United States. In the 1960s, it was expanded to include a number of other domestic groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan, the Socialist Workers Party, and the Black Panther Party. All COINTELPRO operations were ended in 1971. Although limited in scope (about two-tenths of one percent of the FBI’s workload over a 15-year period), COINTELPRO was later rightfully criticized by Congress and the American people for abridging first amendment rights and for other reasons.

Apparently, mainstream textbooks have accepted—hook, line, and sinker—the FBI’s whitewash of COINTELPRO as “limited in scope” and applying to only a few organizations. But COINTELPRO was neither “limited in scope” nor applied only to the organizations listed in the FBI’s description. Under then-FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, COINTELPRO included legal harassment, intimidation, wiretapping, infiltration, smear campaigns, and blackmail, and resulted in countless prison sentences and, in the case of Black Panther Fred Hampton and others, murder. This scope of operations can hardly be described as “limited.” Moreover, these tactics were employed against every national civil rights organization, the antiwar movement (particularly on college campuses), Students for a Democratic Society, the American Indian Movement, the Puerto Rican Young Lords, and others.

A better way to understand the wide net cast by COINTELPRO is the final report of the Church Committee. In the early 1970s, following a number of allegations in the press about overreaching government intelligence operations, a Senate committee, chaired by Democrat Frank Church of Idaho, began an investigation of U.S. intelligence agencies. Their 1976 report states: “The unexpressed major premise of much of COINTELPRO is that the Bureau [FBI] has a role in maintaining the existing social order, and that its efforts should be aimed toward combating those who threaten that order.” In other words, anyone who challenged the status quo of racism, militarism, and capitalism in American society was fair game for surveillance and harassment. Rather than “limited,” the FBI’s scope potentially included all social and political activists, an alarming and outrageous revelation in a country purportedly governed by the protections of free speech and assembly in the First Amendment.

Bringing COINTELPRO into the Classroom

I post a recent headline on the overhead screen: “Top Officer in Iraq: ‘We must neutralize this enemy.'” I ask my 11th-grade U.S. history students, “So what does the word neutralize mean in this headline?” Well-schooled in the popular culture of war and violence, they have no trouble with this task.

“Kill.”

“Destroy.”

“Eliminate.”

“Get rid of.”

I write their definitions on the board and explain we will come back to them in a bit. I say that in this lesson we are going to look at a bunch of old documents from the FBI. I try to build excitement by telling students that these documents were classified top secret and not meant to be seen by everyday folks like us. I continue: “In fact, we only found out about them because a group of peace activists broke into an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, and stuffed suitcases full of documents—selecting the night of a much-anticipated Muhammad Ali-Joe Frazier fight so the security guard would be distracted.”

I post the first document on the overhead for the class to analyze together. It’s a memo sent by Hoover in 1967 to FBI field offices throughout the country: “Black Nationalist—Hate Groups” (see Resources). In it, Hoover instructs his agency “to assign responsibility for following and coordinating this new counterintelligence program to an experienced and imaginative Special Agent well-versed in investigations relating to black nationalist, hate-type organizations.”

At this point in the unit, students have compared the activism of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Congress of Racial Equality, Malcolm X, and the Black Panther Party, analyzing the tactics and social critiques brought to bear by different strands of the movement. Students draw on this background when I ask them to predict which organizations will be targeted under Hoover’s counterintelligence program. “So guys, who are the ‘hate-type organizations’ referred to in this document?”

A number of hands shoot up—students think they’ve got this one. Invariably, their first guess is that the FBI must have targeted the Black Panthers. They explain that the Panthers advocated Black Power and self-defense, and encouraged members to own firearms. Students plausibly predict that if the FBI were to treat any Black activist groups as a potential threat, those with the most revolutionary rhetoric and those bearing arms would have been first in line.

“Well, you’re right,” I say. “So, were the Black Panthers a threat to American security? Did the FBI have a justifiable reason to be tracking them?”

There are always some students who bristle at the militancy of groups like the Black Panthers. Whether it is the Panthers’ use of the term “pig” to describe law enforcement, or Malcolm X’s reference to “white devils,” or the philosophy of self-defense, my students struggle with a discomfort they do not feel when we are talking about SNCC’s sit-ins. I try to help students separate their discomfort about the group’s rhetoric from the question of whether the threat they posed to the U.S. government was a security threat or a political one.

I remind students of prior lessons—the Panthers’ 10 Point Program, their careful adherence to state gun laws to protect them from being charged on weapons infractions, their street patrols to monitor police violence, their breakfast for children programs, their freedom schools.

After some discussion, a consensus usually emerges among my students: White America may not have liked their message or their tactics, but the Black Panthers represented a political challenge. They weren’t doing anything to merit the FBI response.

I continue: “But the Black Panthers were not the only ones targeted. Let’s take a look at the other groups on the FBI’s list.”

I reveal the next page of the document, which states the groups to which “intensified attention under this program will be afforded,” and I ask students to call out other organizations they see listed that we have studied in this unit.

“SNCC!”

“SCLC!”

“CORE!”

I add some humor by acting confused: “Wait a second, can you guys help me out here? Remind me again, who was the head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference?”

Before I am even done with my act of feigned ignorance, students are shouting, “King! King was the leader of SCLC!”

“Oh yes, that’s right! Now help me again because I can’t seem to remember: Was he a member of a ‘hate-type’ organization?”

Students roll their eyes at my poor acting and adamantly confirm: “No! He was all about nonviolence!”

Now I get serious and pause for some analysis and questioning: “OK, folks, what is going on here? Why would the FBI target activist organizations, including those that were explicitly nonviolent, like SCLC and CORE?”

Students offer a few suggestions:

“Maybe Hoover was really racist and didn’t want the Civil Rights Movement to succeed.”

“Maybe the FBI worried that the nonviolent organizations were going to become more militant.”

But this discussion usually ends soon after it begins. Students are flummoxed. They have grown up in a world that glorifies and mythologizes King; they cannot make sense of the notion that U.S. security agencies viewed him as a threat.

In spite of its brevity, this discussion is important. It frames the inquiry to come by cultivating students’ curiosity and confusion.

Now I present to students the final part of the document. This is where Hoover reveals the goal of COINTELPRO:

The purpose of this new counterintelligence endeavor is to expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities of black nationalist, hate-type organizations and groupings, their leadership, spokesmen, membership, and supporters, and to counter their propensity for violence and civil disorder.

I ask a student to read this quote aloud since hearing the words disrupt, misdirect, discredit, and neutralize underscores their sinister meaning.

I remind the class of the earlier definitions of neutralize on the board. I ask, “So what is the FBI saying it wants to do to SCLC, SNCC, CORE, and the Black Panthers?”

Students look at the board, but they can’t quite believe what is written there, so they add question marks.

“Kill?”

“Destroy?”

“Eliminate?”

“Get rid of?”

Most years, there will be a student who interjects at this point to suggest that maybe neutralize means something different in this context; surely it can’t be as bad as I make it sound. This disbelief is the perfect tone to set for the next step of the lesson, when students delve into the documents and see for themselves what the FBI meant by neutralize.

The Documents

I arrange the desks into groups of four. I provide students packets of declassified memos (see Resources) from the COINTELPRO era. These documents are a representative sample of the scope and tactics of the program, and reveal the FBI’s use of infiltration, psychological warfare, legal harassment, and media manipulation against activists and organizations.

I give students a worksheet with some guiding questions to complete as they read and discuss. It mixes retrieval and analysis questions, so students are directed toward the highlights of the documents and the significance of what they read.

For example, for the memo dated 9/27/68, about the Black Panther Party, the worksheet asks, “How does the FBI characterize the Black Panther Party?” Students skim the memo and locate this sentence: “It is the most violence-prone organization of all the extremist groups now operating in the United States.” This is a simple retrieval question. But then I ask, “What activities by the Panthers are not mentioned anywhere in these documents?” Here I urge students to go back to earlier lessons on the social dimensions of the Panthers and recall the breadth of community programs offered by the Panthers, from health clinics to nutrition classes to free breakfasts for children.

I encourage students to tackle the documents together, reading aloud, talking, deciphering, and questioning as they go. These documents can be tough and the copy quality, with lots of redacting, is not always great. Since students are generally very engaged during this lesson, it can get loud.

COINTELPRO and Martin Luther King Jr.

Midway through the packet, students read about the FBI’s program of harassment against Martin Luther King Jr. When they arrive at these documents, I always know, because I start to hear a lot of this:

“Wait, what is this?”

“I am totally confused—this letter was sent to King?”

“Ms. Wolfe, we don’t understand document 6 at all.”

This is my cue to stop the group work and read the King documents together as a class, documents that reveal that through illegal wiretapping, the FBI collected evidence of King’s extramarital affairs and used this evidence to try (unsuccessfully) to blackmail him. The documents show that the FBI not only attempted to discredit King, but also to get him to commit suicide.

It is hard to overstate how dumbfounded the students are by these revelations. How could the U.S. government participate in this level of harassment of a man they have been taught to embrace as a near-deity?

This is a perfect teaching opportunity to help establish the truth about King: He was not the watered-down, Hallmark-holiday caricature that has come to dominate our culture; in the eyes of people like Hoover, he was a dangerous radical who needed to be targeted.

The FBI and Hoover saw King as the radical who, in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” called out racial moderates for their gradualist approach to injustices that required immediate action; the radical whose opposition to the Vietnam War, famously expressed at Riverside Church, led him to describe the U.S. government as “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today”; and the radical who warned Americans, “When machines and computers, profit motives, and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.”

I do not always address all of these dimensions of King with my students, but even just one of these examples helps delineate the breadth of his critique of U.S. society and establish for students why the FBI might see him as a threat and a target of COINTELPRO.

King Was Human

At this moment in the lesson, students want to talk about King’s infidelity.

“Ms. Wolfe, please tell me it is not true that King cheated on his wife!”

“Wait, the FBI made that up, right? To make him look bad?”

I try to limit the length of this conversation, since it is obviously not directly related to the goals of my lesson, but I think it would be a mistake to shut down these heartfelt student questions.

“Yes,” I say. “It’s true, King did cheat on his wife.”

Most students seem saddened by this news and sometimes question whether King’s infidelity discredits and undermines his heroic status. I challenge kids to move beyond this all-or-nothing moral position: “Look, humans are multidimensional. We can be fantastic in one situation, but miserable in another. Imagine if your entire life’s accomplishments were ignored and you were judged only on the basis of the worst thing you ever did. Would that be fair?”

Students begrudgingly take my point but are still sad, as though they have just learned a dark secret about a close family member.

I wonder if there may be a hidden lesson in critical thinking when we reveal King’s moral imperfection to students. If we insist that our activist heroes demonstrate moral perfection—or if we hide their blemishes—do we not in some way transmit the message to young people that heroic action is something for a small elect, the untarnished few, not for imperfect people like you and me?

The Murder of Fred Hampton

We’ve clarified the goals of COINTELPRO and learned about the actual strategies, methods, and targets of the program. But, so far, COINTELPRO has been revealed only on paper. Now it is time to show students how the program damaged and destroyed people’s lives.

I show students an excerpt of the documentary Eyes on the Prize — part of the episode “A Nation of Law?” that details the story of Fred Hampton. Hampton was a former NAACP youth organizer who became the chair of the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party in 1968. Hampton embodied what was powerful and promising about the Panthers. At just 20 years of age, he helped the Panthers establish a breakfast for children program and a free medical clinic on the South Side of Chicago. He taught political education classes and was working to create a multiracial “rainbow coalition” of Chicago youth groups that included the Blackstone Rangers (a street gang), the Young Lords, and the Young Patriots, an organization of working-class white youth, often migrants from Appalachia. Howard Saffold, a member of the Chicago Police Department at the time, eloquently sums up law enforcement’s concerns about Hampton’s coalition-building:

The Panthers were pursuing an ideology that said we need to take these young minds, this young energy, and turn it into part of our movement in terms of Black liberation and the rest of it. And I saw a very purposeful, intentional effort on the part of the police department to keep that head from hooking up to that body. It was like, you know, do not let this thing become a part of what could ultimately be a political movement, because that’s exactly what it was.

Like most of the leaders of the Black freedom movement, Hampton drew the interest of the FBI and COINTELPRO. In 1969, following months of harassment, Hampton was shot and killed as he slept in his bed, his pregnant partner beside him, during a police raid on his home. He was 21 years old.

As they watch the documentary, students take notes on the facts of the Hampton case, and we stop the film often to discuss what we see and hear. I help them tease out the COINTELPRO dimension of the story: an FBI informant infiltrated the Chicago chapter of the Panthers and earned Hampton’s trust. He proceeded to provide a floor plan of Hampton’s apartment, noting which room he slept in. This information was used by the raiding officers who killed him.

Following the film, students complete a viewer response journal to talk back to the film, a way to process the horror, shock, and grief many of them feel after watching the deadly consequences of COINTELPRO. Aiden grapples with Hampton’s innocence: “The police had no reason to come to Hampton’s house like that and open fire. He wasn’t hurting anyone and he hadn’t done anything wrong.” Carrie echoes an elderly woman quoted in the film: “The tragic death of Fred Hampton was ‘nothing but a Northern lynching.'” Avery writes: “A mob of people came into Fred’s home, for no reason, and murdered him. The fact that these were police officers only made it more unbelievably awful.”

The Hampton murder also serves as a moment to bring students back to our earlier discussion of the word neutralize. Did the FBI target Hampton for murder? Although FBI agents did not pull the trigger on the weapons that killed Hampton, they provided critical information to those who did. It is clear to students that murder was an acceptable outcome in the larger project of destruction undertaken by COINTELPRO.

Indicting COINTELPRO

I usually end this lesson with students writing a piece related to the Church Committee report. The report concludes, in part:

The findings which have emerged from our investigation convince us that the government’s domestic intelligence policies and practices require fundamental reform. . . . The Committee’s fundamental conclusion is that intelligence activities have undermined the constitutional rights of citizens.

After reading this statement, I lead a quick discussion of which constitutional rights the report might be referring to; students have recently studied government, so it doesn’t take long for them to recall the Fourth Amendment’s privacy protections, the First Amendment’s speech and expression protections, and the Fifth Amendment’s due process protections. We also use this discussion to recall examples from our investigation of the COINTELPRO documents that demonstrate the government infringing on these rights. Finally, I ask students to use the committee’s statement as the thesis for some in-class writing.

The prompt reads:

Based on the documents you read and the film you watched, write at least two supporting paragraphs for the excerpt from the Church Committee’s conclusions. In order to do this you will need to:

- Identify protections in the Bill of Rights that were denied or abused by COINTELPRO.

- Identify examples from the COINTELPRO documents or the film that prove that the rights of activists were abused.

- Explain and analyze how the evidence in the documents proves that a constitutional injustice occurred.

Admittedly, this is a rather dry academic exercise, but it requires students to formalize their thinking about COINTELPRO as they craft what amounts to an indictment. The task requires students to show, unequivocally and unambiguously, that COINTELPRO was not just unethical and unjust, but illegal too.

Final Thoughts

When I first started teaching about COINTELPRO back in the early 2000s, I ended the unit with a discussion of then-President George W. Bush’s NSA surveillance program, which had recently been exposed and was being hotly debated; more recently, I have drawn connections to the Edward Snowden revelations. This year I will address government tracking of Black Lives Matter activists and the use of social media platforms to gather intelligence on protest movements and protest leaders. It seems that the questions of surveillance and government overreach are never out of date.

COINTELPRO is not just a surveillance story. It is a story about a duplicitous and destructive government-sponsored war against Black and other activists. And though the COINTELPRO documents have long been made public, it is a story history textbooks continue to ignore.

Textbook publishers’ disregard for the history of COINTELPRO is one more example of the crucial importance of the Black Lives Matter movement, which lays bare the systemic dangers faced by Black people in the United States while simultaneously affirming and celebrating Black life. When activists use social media to show the nation the brutal strangulation of Eric Garner or the mowing down of Tamir Rice or the deadly harassment of Sandra Bland, we cannot fail to recognize the injustice and racism of the criminal justice system. When that same social media shows us Garner’s wife pleading, “He should be here celebrating Christmas and Thanksgiving and everything else with his children and grandchildren”; or a photo gone viral of Rice as a shy, smiling boy; or a Facebook post of Bland looking joyful about a new job—we feel the human potential lost as a consequence of these injustices.

What I attempt in my classroom is a Black Lives Matter treatment of COINTELPRO, where we reveal the injustice of the program while simultaneously affirming and celebrating the promise of the activists it sought to silence. Just as Black Lives Matter activists use video footage to convince a disbelieving wider public of what African Americans have long known about police brutality, we teachers can use our classrooms to shine a light on history that has been available, but systematically ignored, by our textbooks and in our curricula, a history that emphatically communicates: Black history matters.

Resources

Goldfield, David, et al. 2005. The American Journey: A History of the United States. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Pearson.

Henretta, James A., David Brody, and Lynn Dumenil. 2006. America: A Concise History. St. Martin’s.

McClenaghan, William. 2005. Magruder’s American Government. Pearson.

Nash, Gary. 2004. American Odyssey: The 20th Century and Beyond. McGraw Hill.

PBS. 1990. “A Nation of Law?” Eyes on the Prize. Produced by Henry Hampton. Blackside.

COINTELPRO Documents

Unless otherwise indicated, the following documents can be found in Churchill, Ward, and Jim Vander Wall. 2001. The COINTELPRO Papers: Documents from the FBI’s Secret War Against Dissent in the United States. 2nd ed. South End Press:

Dec. 1, 1964. FBI memo about “taking steps to remove King from the national picture.” The memo suggests sending Martin Luther King Jr. an anonymous letter encouraging him to commit suicide. p. 98. A clean, unredacted version of the letter to King and be found at nytimes.com/2014/11/16/magazine/what-an-uncensored-letter-to-mlk-reveals.html?_r=1.

Aug. 25, 1967. Memo from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover initiating COINTELPRO against civil rights organizations. vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists/cointelpro-black-extremists-part-01-of/view.

March 8, 1968. FBI memo suggesting misinformation leaflets be distributed in Baltimore to combat the influence of new SCLC offices opening there. vault.fbi.gov/cointel-pro/cointel-pro-black-extremists/cointelpro-black-extremists-part-01-of/view, p. 78-79.

July 10, 1968. FBI memo proposing false information be used to “convey the impression that [Stokely] Carmichael is a CIA informant.” p. 128.

Sept. 27, 1968. FBI memo describing the Black Panther Party as the “most violence prone organization . . . now operating in the United States,” with FBI plans to create factionalism within the party. p. 124.

Oct. 10, 1968. FBI memo in which a “media source” is sought “to help neutralize extremist Black Panthers and foster a split between them and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.” p.127.

December 1969. Floor plan of Fred Hampton’s apartment, as drawn by an FBI informant. p. 139