Climate Change, Gender, and Nuclear Bombs

Column: Earth, Justice, and Our Classrooms

In the spring 2011 issue of Rethinking Schools we editorialized about the immense gulf between our terrible environmental crisis — especially the climate crisis — and the adequacy of schools’ curricular response. Seven years later, we still see this gap between crisis and curriculum — which is why we are launching this regular “Earth, Justice, and Our Classrooms” column: to offer encouragement and resources for teachers to help students explore the roots and consequences of the crisis and figure out how to respond.

At the urging of teachers, parents, students, and community activists, in the spring of 2016 the Portland, Oregon, school board passed a sweeping climate justice resolution. A key part of the resolution states, “All Portland Public Schools students should develop confidence and passion when it comes to making a positive difference in society, and come to see themselves as activists and leaders for social and environmental justice — especially through seeing the diversity of people around the world who are fighting the root causes of climate change.”

The resolution calls on teachers “to investigate the unequal effects of climate change and to consistently apply an equity lens as we shape our response to this crisis.”

As with so much else in the world, gender is one of the crucial variables determining how the climate crisis affects us.

Catherine Pearson’s short, classroom-friendly HuffPost article, “Why Climate Change Is a Women’s Issue,” summarizes how many of the key features of climate change — drought and uncertain rainfall, rising sea levels, more frequent superstorms, spread of new viruses, rising temperatures, and worsening air quality — often hit women harder than men. Women in poor countries spend more of their time finding water and collecting fuel. For a host of reasons, women are much more likely than men to be killed in natural disasters, and much more vulnerable to the rape and abuse that so often follow the trauma of climate-related hurricanes, floods, or wildfires. Most of the world’s farmers are women, and the ravages of climate change more quickly upend their lives. Rising temperatures worsen air pollution, which can cause respiratory distress for pregnant women and lead to low infant birth weight. And on and on. Of course, women are not only the victims of climate change, but also some of its most formidable opponents. Around the world, women activists are on the front line of the fight against the oppressive systems hastening our climate crisis.

For the past two school years, Portland’s Climate Justice committee, charged with implementing the school board’s resolution, has had the good fortune to partner with one of those activists, the Marshall Islands performance poet Kathy Jetil-Kijiner. (See Michelle Nicola’s “Teaching to the Heart: Poetry, Climate Change, and Sacred Spaces,” Rethinking Schools, summer 2017.) Kathy has led two professional development sessions for teachers and community members. So far, she has given more than 30 presentations to about 2,000 students — all supported by the school district, thanks to the climate justice resolution.

Too often, climate change is framed as an environmental issue — about carbon dioxide, melting glaciers, ocean acidification, and polar bears. Kathy emphasizes that climate change is much more; it’s about the intertwined legacy of colonialism, racism, militarism, sexism, and a profit-driven economic system. And in the Marshall Islands, the climate catastrophe is layered onto the tragic history of nuclear testing, which has taken an especially harsh toll on women through its horrible legacy of miscarriages and birth defects.

Like other colonized people who have been invaded, bombed, abused, and lied about, the Marshallese have an intimate relationship with the violence of colonialism and the violence of climate change. As Kathy writes on her blog:

I have been passionately advocating against climate change because of my deep sense of fear that our islands will one day be wiped off the map, due to the rising sea levels. But I never realized that we, some of us more than others, have already known the pain of lost homelands. Three [Marshall] islands have been literally vaporized because of the power of the bombs. Bikini and Rongelap atoll are forever lost to our people because of high levels of radiation. This is a loss we’ve had to bear “for a greater good” — a reasoning that is very similar to those who are convinced that our need for consumption outweighs the livelihoods of others.

For an International Women’s Day blog post a couple years ago, Kathy wrote about the impact of nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands:

From 1946 to 1968, 67 nuclear weapons were detonated, which is the equivalent of 1.7 Hiroshima bombs being exploded daily for 12 years in terms of radiation exposure. Just the Bravo shot alone, a 15-megaton hydrogen bomb, was 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima.

Women disproportionately bear the burden of the trauma their society has been exposed to — in this case, they bear the burden of a nuclear legacy. It was women who found themselves with birth defects after exposure to the radiation and fallout. “Jellyfish babies” is what they call them. Tiny beings with no bones.

Kathy elaborates in her poem, “History Project”:

the miscarriages gone unspoken

the broken translations

I never told my husband

I thought it was my fault

I thought there must be something wrong

inside me

I flip through snapshots of American marines and nurses

branded white with bloated grins

sucking beers and tossing beach balls

along our

shores

and my islander ancestors

crosslegged before a general

listening to his

fairy tale

about how it’s

“for the good of mankind”

to hand over our islands

let them blast

radioactive energy

into our lazy limbed coconut trees

our sagging breadfruit trees

our busy fishes that sparkle

like new sun

into our coral reefs

brilliant

as an aurora borealis woven

beneath a glassy sea

An essential classroom resource on this hidden history is the film Nuclear Savage: The Island Experiments of Secret Project 4.1. The racism of nuclear testing is breathtaking. In 1956, Merril Eisenbud, director of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission’s health and safety laboratory, described plans for sending Marshallese back to the atoll of Rongelap, just three years after the largest nuclear test in history: “That island is by far the most contaminated place on Earth and it will be very interesting to get a measure of human uptake when people live in a contaminated environment.” As if that were not outrage enough, he added, “While it is true that these people do not live the way Westerners do, civilized people, it is nevertheless also true that these people are more like us than the mice.”

In addition to “History Project,” Kathy’s poems “Dear Matafele Peinam,” “Tell Them,” “Fishbone Hair,” “Two Degrees,” “Utilomar,” — all available as video performances online — and the agonizing new poem, “Monster,” introduce middle and high school students to how climate change is embedded in a web of colonial and gender oppression. Kathy points out that the Marshall Islands society is matrilineal. “Our mothers bestow land rights and chiefly titles. We believe that it is through our mothers that we receive power. But what will happen to that power if there is no land to pass down?”

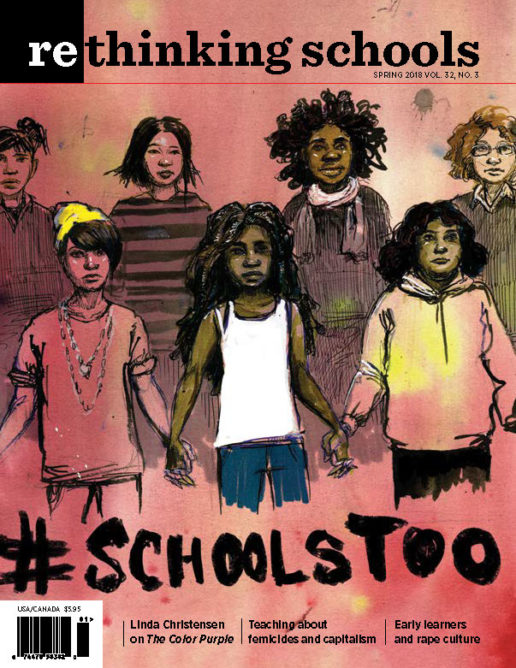

Our climate justice resolution in Portland talks about the importance of centering the lives of “front line” people in our curriculum — Indigenous peoples in the Arctic, sub-Saharan Africa, Bangladesh, Pacific Islands, and throughout North America. Especially at this #MeToo/TimesUp moment, the work of Kathy Jetil-Kijiner is a vital resource to remind students that women are in the front line of the front line — not just as the victims of colonialism and climate change, but as poets and protesters, actors, and activists. As Kathy reminds us on her blog — and as we see with each passing day — women are giving “birth to a new life, to fresh possibilities.” n

Kathy Jetil-Kijiner’s work can be found at her blog, jkijiner.wordpress.com, and in her book Iep Jaltok: Poems from a Marshallese Daughter (University of Arizona Press, 2017).