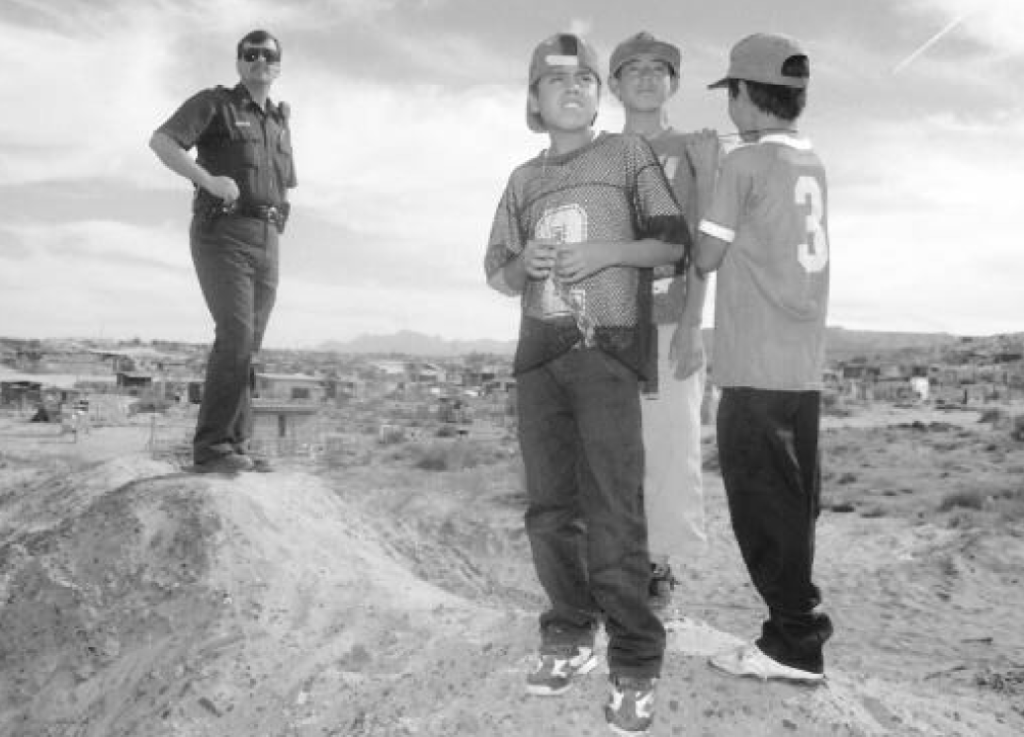

Civil Rights 101, Tex-Mex Style

How an El Paso School Took on the Border Patrol

A U.S. Border Patrol agent talks with children on the border between Sunland Park, N.M., and Puerto de Anapra, Mexico. This portion of the border is about four miles from Bowie High School. The Rio Grande, which is the actual border between Texas and Mexico, runs about 75 yards from Bowie High.

To his classmates and teachers at Bowie High School in El Paso, Texas, David Renteria’s story was all too familiar.

The 19-year-old senior was walking home from a graduation rehearsal at Bowie in June of 1992 when a U.S. Border Patrol truck pulled up to him and an agent told him to stop. He refused, saying he was a U.S. citizen who was exercising his right not to answer any more questions. At that point, Renteria said later, the agent jumped from the truck, pushed him face-first into a chain-link fence, kicked his legs apart, and frisked him with hard open-hand slaps to his legs and body.

Renteria told his story to a few local news reporters, but little came of it. The Border Patrol flatly denied that any abuse had taken place, and public interest in the incident quickly faded.

In El Paso, a dusty west Texas city of 600,000 people that sits on the U.S. border with Mexico, that’s how it usually went. The Border Patrol’s light-green trucks were common sights throughout the city and the surrounding desert. Agents seeking undocumented immigrants from Mexico apprehended more than 1,000 people every day and questioned many more.

Because Bowie High sits right on the northern bank of the Rio Grande, separated from the border only by a four-lane highway and a chain-link fence, the Border Patrol always maintained a strong presence in the area. As a federal agency, the Border Patrol didn’t answer to local government or law enforcement. They cruised the streets around Bowie High, and even the campus itself, with virtual impunity.

The most unusual thing about Renteria’s story, in fact, was that he had bothered to tell it at all. Many people who lived in the poor, virtually all-Hispanic neighborhood surrounding Bowie High — as well as teachers and administrators who worked at the school — had endured similar encounters with Border Patrol agents. While many people felt the Border Patrol had harassed or brutalized them, most saw no point in coming forward. “It had been going on for generations; it was so prevalent that it was accepted,” Bowie teacher Juan Sybert-Coronado recalled recently. Sybert-Coronado tried to encourage students to file complaints against the Border Patrol, “but almost no one was willing,” he said. “They felt shame for what had happened to them, they didn’t want everybody to know, and they didn’t think they could do anything about it.”

Renteria’s story might have been forgotten as well, had Bowie High not gotten a new principal that summer named Paul Strelzin.

A NEW FACE ON CAMPUS

A bear-sized man in his 50s whose booming voice is laced with the accent of his native Brooklyn, Strelzin served as a teacher and principal at several El Paso schools before coming to Bowie. But he is perhaps better known in the city as an announcer and pitchman. He hawks auto parts in TV and radio commercials and has presided over countless local sporting events, mercilessly ribbing the opposing team and cheering on the hometown favorites. “The Strelz,” as he is known, has built a reputation as a person willing to speak his mind: He was once ejected from the announcer’s box at a Texas League baseball game after responding to an umpire’s questionable call by playing a Linda Ronstadt song that begins, “I’ve been cheated.” As a principal, Strelzin had also earned a reputation as a hands-on leader, clearly “the person in charge” of every aspect of “his” school. He was also known as a dedicated advocate for students, who aggressively pursued whatever course of action he felt was in their best interest.

Strelzin hadn’t been at Bowie long “before I began to notice a dark undercurrent running through the school,” he said recently. “It was as if there was a cloud hanging over the campus. But nobody would talk about it.” When he asked staff members what was going on, he began hearing stories about the Border Patrol. His secretary told him she had been followed from campus one night by agents who searched her car, questioned her, and then drove off without a word of explanation or apology when they found nothing. A football coach said he’d been driving students to a game at another school the previous fall when he was pulled over and frisked by Border Patrol agents, one of whom pointed a gun at his head. Sybert-Coronado told Strelzin that he knew many students had suffered similar abuse, but that they were afraid to come forward.

It wasn’t long before Strelzin began compiling his own list of problems with the Border Patrol. Agents driving their trucks on the school grounds were destroying the school’s sprinklers. Other agents chasing suspects on foot sometimes ran through school buildings. People on or near the campus were stopped, searched, and questioned for “suspicious activities” that included picking someone up at school in a car or carrying a backpack.

One morning Strelzin approached a Border Patrol truck idling in a school parking lot and encountered agents “who were sitting there looking at my flag girls with their binoculars. When I asked them what they were doing they said they were watching a white car that was possibly involved in a drug deal, but I was standing right there, there was no white car visible between there and Los Angeles.”

Hoping to regain control of his campus with little commotion, Strelzin invited Dale Musegades, the local Border Patrol chief, to come to his office and talk things over. But the meeting brought the principal no satisfaction. Musegades dismissed the stories of Border Patrol abuse as lies, saying no one had ever filed a formal complaint with his office. When Strelzin asked Musegades to keep his agents off the school campus, the chief flatly refused. “He told me that within 25 miles of the border he was the law, and he could do whatever he wanted,” the principal recalled. “So I went back to my staff and we talked about it, and we decided it was time to do something.”

A TWO-PRONGED STRATEGY

In the months that followed, Strelzin did two critical things. First, he publicly accused the Border Patrol of harassing Bowie students and staff. At school board meetings and in interviews with local news media, he repeated the stories he’d been told, and complained about the Border Patrol’s refusal to admit any wrongdoing. “Here was someone that couldn’t be dismissed as a radical,” Sybert-Coronado remembered. “He was a good old boy with a solid reputation in the community.” Suddenly the media, which had paid only modest attention to allegations of Border Patrol abuse when people like David Renteria had made them, decided that the Border Patrol’s activities at Bowie High were front-page news.

Second, and more importantly, Strelzin supported efforts by Sybert-Coronado and other teachers to begin dealing with the Border Patrol in bold new ways. Sybert-Coronado invited members of the El Paso Border Rights Coalition, a local activist group, to come on campus and begin working with students. “In another school, with another administrator, I would have been fired, and people like the coalition would have never set foot on the campus,” Sybert-Coronado said. Strelzin “was willing and able to deal with people in the [school district] administration who wanted to support the status quo.”

Coalition members visited Bowie several times that fall, telling students about their rights to due process when dealing with Border Patrol agents. “A lot of them were asking if they had to open their car trunks, if they could really walk away,” said coalition member Suzan Kern. “It was hard for them to believe they had any rights at all.”

Then the coalition got a phone call from David Renteria, who told the story of his encounter with the Border Patrol on the way home from graduation rehearsal. The coalition contacted a San Antonio-based group called the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights, which sent lawyers to El Paso to take a sworn statement from him and from anyone else at Bowie High willing to go on the record against the Border Patrol.

Strelzin, Sybert-Coronado, and other staff members at Bowie began urging their students and colleagues to come forward. “Once the first person or two had given a statement, the dam broke,” Kern said. “All of a sudden we had 20 people who wanted to give statements, and kids were bringing us phone numbers of other people who had stories to tell.”

THEIR DAY IN COURT

Armed with dozens of sworn statements, the San Antonio lawyers filed a federal lawsuit against the Border Patrol in October 1992. As part of the suit, they filed a motion for a temporary injunction to keep Border Patrol agents from performing unwarranted searches of Bowie students and staff. At a hearing on the motion, Musegades, the Border Patrol chief, said he would investigate the incidents described in the depositions, but complained that none of the allegations had been reported to his office before. The agents identified in the depositions denied any abuse.

Federal Judge Lucius Bunton weighed the evidence and decided that the Bowie students were telling the truth, and that the Border Patrol had abused its authority. In December he granted the temporary injunction, and gave the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights permission to seek more victims and pursue a possible class-action lawsuit against the Border Patrol. In his ruling, Bunton declared that people in the Bowie neighborhood had been “repeatedly stopped, questioned, detained, frisked, searched, and arrested without legal cause, and have been subject to verbal and physical abuse,” simply because they looked Hispanic. “The government’s interest in enforcing immigration laws does not outweigh the protection of the rights of United States citizens and permanent residents to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures,” he wrote.

The ruling “was a cause of great celebration at Bowie,” Sybert-Coronado remembered. “The students (and staff members) had participated in government, they made it work for them. And the community felt the kids had struck a blow against the discrimination they all felt because they happened to have brown skin.”

AFTER THE RULING

In the three years since Bunton’s ruling, several important events have shaped the Border Patrol’s role in El Paso.

First, the Border Patrol and plaintiffs in the Bowie lawsuit agreed to a settlement, which prohibits Border Patrol agents from conducting unwarranted searches in the Bowie neighborhood. Under the settlement, the Border Patrol also agreed to several steps that make the complaint process easier and more reliable. They include putting bumper stickers on Border Patrol trucks with the agency’s phone number, creating a bilingual complaint form and a 24-hour toll-free phone line providing information about the complaint process, and maintaining strict requirements for acknowledging and processing complaints. Judge Bunton approved the settlement and stipulated that the Border Patrol’s behavior would be strictly monitored for five years. In January he rejected a Border Patrol request to dismiss the lawsuit and end the monitoring.

Second, in September of 1993, almost a year after Bunton’s initial ruling — and shortly after Dale Musegades retired — the Border Patrol radically changed its tactics in El Paso. Instead of cruising the city looking for undocumented immigrants, agents formed a blockade directly on the border, by parking their trucks within sight of each other in a line stretching from one end of the city to the other. Overnight, the number of undocumented immigrants crossing the border in El Paso dropped from thousands per day to nearly zero.

Many observers saw the blockade as a result of the Bowie lawsuit and the damage to the Border Patrol’s reputation it caused. Sybert-Coronado is one of them, “and to be honest, I feel a lot of guilt,” he said. “We won, but as a result, thousands of people a day are prevented from going to work, earning a living. It’s causing starvation on the other side of the river. So in the short run it was great, but in the long run, it’s horrible.”

Stories of abuse by Border Patrol agents continue to surface as well, said Kern of the Border Rights Coalition. “With the blockade, the action has moved out of El Paso and into the smaller communities on the outskirts of the city,” she said.

Sybert-Coronado — who now heads a Chicano studies department at Bowie, the only state-recognized high-school program of its kind in Texas — tries to raise some of these issues with his students. “They need to understand that there are no simple answers,” he said. “We try to deal with the fact that things are better in their neighborhood now, but that other people still have problems. And that the people on the other side of the border are no different from us, they’re not less than we are, they’re our cousins. They just didn’t emigrate when we did.”

Despite his misgivings, Sybert-Coronado points with pride to positive outcomes from Bowie High’s struggle with the Border Patrol. “There’s no doubt in my mind it led to a sense of empowerment among students and their parents,” he said. “We have 250 parents in our PTA now. Back when everything started, we barely had any. But then suddenly the school was an institution that had made a positive impact on their lives, and they wanted to get involved.”

Strelzin echoed Sybert-Coronado’s optimistic assessment. “The cloud that used to hang over Bowie High School is gone,” he said, “and students know that they have the right to be treated as human beings.”