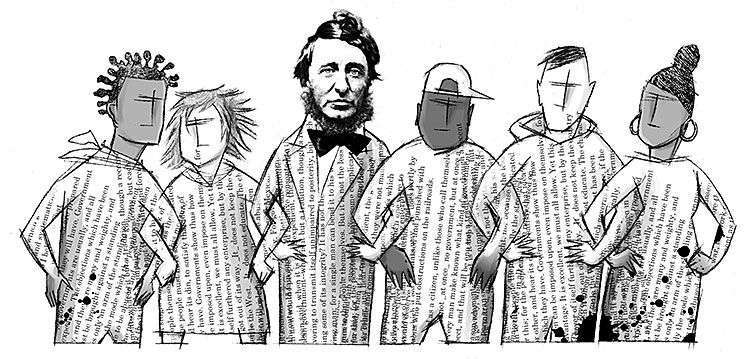

Civil Disobedience

Illustrator: Christiane Grauert

Students swarmed my car. As I turned off the engine, I heard their buzzing voices, charged and anger-filled. I rolled down the car window and asked them to step back so that I could exit the car. Everyone talked at once:

“Robbie is gonna go to jail if you don’t do something!”

“She wrote everyone in the classroom up!”

“We didn’t do anything wrong.”

“That substitute is a bitch!”

“We did exactly what you told us to do!”

“Jessie cried!”

“We were practicing civil disobedience—just like you taught us!”

I raised my hand. Their attention captured, I said, “Let’s go up to my room and you can tell me what happened—one at a time. I’ll read the report left by the substitute and we’ll figure things out.”

The students who gathered around my car and followed me to my classroom were enrolled in an alternative high school. Their ages ranged from 15 to 21. The educators who referred them to our school considered them “at risk.” I considered them courageous. Some of my students, in just 16 short years of life, had faced challenges and difficulties that I would never face. For some, school was safer than their homes and neighborhoods. For others, school was the place where they ate a full meal and were warmly greeted by an adult every day. Others learned how to parent their children. Everyone received counseling, social services, and medical care.

The previous day I had attended a workshop. In preparation for my absence, my students and I made a plan so they could be successful in my absence. I expected their best behavior while I was gone. I also expected them to go easy on the substitute and treat her like they would treat me—respectfully. The last time I was absent, my students snookered the substitute. They told him that I let them play their personal CDs in class —which was true. Unfortunately, they omitted the detail that I did not allow CDs that contained profanity. The class was listening to comedian Andrew Dice Clay, who spews the F-word, when the principal walked into the room. That substitute was never allowed on campus again, and the CD player was silent in class for several weeks.

Even for an alternative school, this class was diverse. When I first viewed the roster, I wondered to myself, “Can I build a classroom community with this group?” The class contained many streetwise students with the “grit” to survive. The character traits that allowed them to navigate their often-hostile world also made them a challenge to teach. And then, my job was made more complex by a group of young women described as the “Church Ladies.”

The Church Ladies kept to themselves. They always entered class together, sat together, and left together. Although they were 17 and 18 years old, they often wore flower print dresses with lace collars, more like grandmothers than teenagers. It was clear to most of us—students and staff—that they were emotionally fragile. For example, Jenny panicked the day she scratched a mole on her face and it began to bleed. It was her favorite mole and she was afraid it would fall off. When Carly became anxious about something, she gouged and scratched her arms with her fingernails until they bled. Ruthie did not make eye contact with anyone.

In my room, their classmates demonstrated a daily consideration and kindness to these young women. In a class where students were not assigned seats, they always arrived to find the three seats they preferred vacant. This was true even when they were the last to arrive.

Building Trust

On the first day of class, Carly leaned over to me and whispered, “I don’t read out loud.” I said: “I have to know that you can read and what your reading level is. Will you come in during lunch and let me do an assessment? But I promise you that I will never call on you to read aloud in class.”

Carly passed her assessment. With our agreement in place, Carly asked me what I would tell the other students. I told her than no one else had to know. She then asked me if our agreement was fair to the other students. I told her that my definition of fair meant giving folks what they needed to succeed, not treating everyone the same.

Actually, I never called on any student to read aloud. Students volunteered to read. If they did not want to, they did not have to; they could follow along and read silently. In a given day, some students read more than once, others did not read aloud at all. The only rule in place was to begin and end at a paragraph.

Over time I learned that Carly enjoyed reading. She often read a book and then watched a movie based on the book. I kept a file cabinet in my classroom and stored some movies in one of the drawers. One day Carly asked if she could borrow a movie. I said, ” Of course,” and asked her to leave a note in the drawer.

I was surprised several days later to discover a note and a book in the file drawer. Carly had left both. She had read the book, liked it, and thought I would, too. The next day I asked her to check the file drawer, where she found a short letter and a book that I left for her. This is how our file cabinet relationship began. Carly and I exchanged books and we both wrote thoughtfully about our reading. Carly did not talk to me in front of the class, and I never asked her to read aloud. But I eagerly awaited each installment in the file cabinet dialogue.

What Is Civil Disobedience?

Building trust and community was central to how I approached all our work, including our reading of Henry David Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience.” Almost all of my students knew about being locked up—either from their own experience or someone close to them, so I knew we would find a lot to talk about. I started by connecting the essay to history the students were more familiar with; for example, I told them how Thoreau influenced Martin Luther King Jr., and we recalled examples of civil disobedience from the Civil Rights Movement.

Then I asked: “Has there been a time in your life when you felt compelled to civil disobedience?” I asked them to work first in their Thinking Logs, where they were free to express themselves through free writing, drawing, creating thought webs, whatever helped them get thoughts on paper. When I asked for volunteers to share their ideas, Shanna, who was 15, said she had engaged in civil disobedience: She went to “juvie” for 10 days instead of snitching on her best friend. Her example led to a lively discussion. About half the students agreed with her. Others, particularly the older students, saw things differently. She was loyal to her friend, they said, but civil disobedience is a political stance; it needs to be about a political principle and it needs to be directed against authority.

That early discussion led to interest in the essay, even as we struggled with difficult vocabulary and complex ideas. After each chunk that we read aloud (and I did more of the reading than usual), the students continued talking about what civil disobedience looks like and when it is justified—in small groups and all together.

A Substitute Rocks the Boat

My sub plans called for the students to read aloud as they normally did from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. I left detailed plans that stated how many pages the class should read. I carefully explained the way we read aloud and that she was not to call on students. I also noted that Ken, a student in the class, was prepared to help her.

The substitute ignored my directions. She used the roster to call on students to read. She told them when to start and when to stop. When Ken tried to explain the reading policy to her, she wrote up a discipline referral for him; the charge was insubordination. After this, the students grudgingly went along with the substitute, reading aloud and stopping and starting when she told them to.

Then she called on Carly.

Robbie laid his book down on his table, crossed his arms over his chest, and told the substitute he was done reading for the day. Every other student in the classroom followed his example. Carly was the last student to turn her book over. This class of high school students then sat in silence for 63 minutes until the class ended. The substitute wrote up discipline referrals for all of them. And for some of these students, a discipline referral was high stakes—it could mean re-incarceration.

What Would Thoreau Do?

After learning the students’ side of the story, I walked to my principal’s office. I tried to anticipate his reaction as I knocked on his door. He waved me in and said, “I thought I would be seeing you this morning.”

“I heard there was some trouble yesterday, Mr. Burns. I have heard the students’ report and I read the substitute’s report, and now I would like to check with you to see how you want to handle this. I understand she wrote up every student in the class.”

Mr. Burns pointed to the stack of pink discipline referrals on the corner of his desk. “Well, Ms. Stevens, I thought I would let you handle this.”

“It seems to me that our students acted courageously. The substitute did not follow the explicit directions I left. The stronger students in that class protected a very fragile student. They recognized her humanity. And, really, when was the last time one student, much less more than 20, were written up for sitting quietly?”

Mr. Burns grinned. I grinned back at him, picked up the referrals, threw them in the trash, and exited his office.

Stepping into the hall, I paused, drew a deep breath, and leaned back against the wall. Overrun with emotions, I wanted to cry, smile, and laugh hysterically all at the same time. The students and I had built a classroom community—and they had internalized a work of literature we studied.

Getting my emotions under control, I returned to my classroom and was greeted by . . . silence. The passionate, vocal students who gathered around my car in the parking lot sat in postures of forced nonchalance. Warily, they watched me. Students who attend alternative schools have already learned that life isn’t fair and that “right action”—at least right action from them—can still be punished.

I smiled. Hope sparked in the eyes of some of the students. Still no one spoke. “Mr. Burns let me decide what to do with the discipline referrals, so I threw them in the trash.” One young man tipped his head back and covered his face with his hands. Another young woman pumped her arm and smiled fiercely. Two students clasped hands in a sign of unity. I said: “You did the right thing here. I’m proud of all of you.”

Ken stood, raised both arms over his head in a “V,” clenched his fists, leaned back and shouted, “YES!”