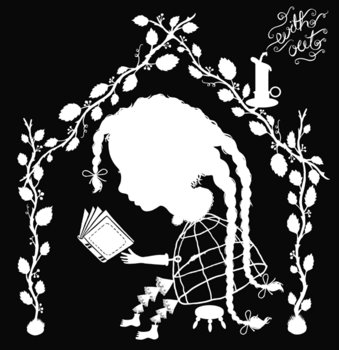

Candles in April

Illustrator: Melinda Beck

This story has lived in me for more than 25 years. I was in the 7th grade. This is a time when how others see you is crucial to your existence. One beautiful spring day in April I came home from school. My mother was always home when I arrived in the afternoon, so I expected her to be in one of her two usual places: in the kitchen reading and watching television, or in her bedroom. However, as I was putting my things away, I noticed that the house had an unusual silence, a stillness.

My first thought was that perhaps my mother wasn’t home. As I went to investigate, I heard the rattling of the newspaper. I immediately had a sinking feeling. Before I could ask why the television was quiet, she said matter-of-factly, “Yep, it’s off.” The look on her face told it all.

I sighed deep and long as I sank into the couch. I looked at the clock. It read 9:25. I thought to myself, “So that’s when they cut the power off.” I asked my mother what we were going to do, what she was going to do.

“Well, we will have to get batteries and go find the flashlights, candles, and matches until I can figure something out. We’ll also have to get ice and coolers to keep the food cold. Don’t open the refrigerator too much. For now, we need to keep as much of the cold in as we can.”

We’d experienced this before, but it was usually a temporary situation, a matter of a few days or so. This time, three months went by until my mother “figured something out.” It was hard. During those months, life for me was a different experience—to say the least. It was different from the majority of my peers and certainly different from my teachers.

For the most part, school was my salvation. There were lights and people and sounds. I could be with my friends, although I remember wishing that I could go home with them. Every day, the final bell rang me back to reality.

One day, one of my teachers noticed me moving slowly during dismissal. Most of my classmates were excited to go home to watch television and, as the weather warmed up, to get outside and play. They had the option of doing their homework later. They had electric lights. They weren’t on the same kind of time schedule I was on. My well-meaning, white, middle-class teacher said to me: “Smile, the bell just rang! It’s a beautiful day! Aren’t you excited to go home?

“No, not really,” I said.

“Oh, nothing’s that bad. Come on, you kids don’t know what real problems are. You’re too young!”

Well, I did know what real problems were. Once I got home it was like a beat-the-clock game. I had to get my homework done while there was still enough daylight to see; I hoped to have time to get outside, too. After dark, the candles didn’t produce enough light. I also had to worry about how much life was left in the flashlight batteries. And I had to share the light sources with my brother. My mother had her own; she was good at rationing out what we needed to make it last. These were “real” problems for me.

In the best of circumstances, middle school can be a tough time. I worried how long it would take the neighborhood kids to find out about our situation. The daytime wasn’t so bad. We didn’t use much light anyway, and at times I would forget we didn’t have power. For a little while, my house felt normal. But when it started to turn dark, when the streetlights and everyone else’s house lights came on, that’s when the panic and despair set in.

How long before everyone would notice that our house remained dark? A dark house could, of course, mean that no one was home. But when we were home, everyone knew it. A dark house at night was like a huge announcement to the world: THEIR POWER IS OFF!! During adolescence, this was one of the worst kinds of embarrassment to have to endure.

Naturally, my teachers didn’t know what was I was going through. I didn’t talk about it. I couldn’t. We didn’t dare tell “our business” at school.

“Those people are nosy, and they will be in our business.” This is a mantra I was raised by. “Those people,” of course, were white and middle class. I wasn’t sure my teacher would understand. And I didn’t want her to ask too many questions that I couldn’t answer.

I remember April as a time of hardship because that was the month that the “people” came to shut your power off. They did, that is, if you followed the you-don’t-have-to-pay-during-the-winter-because-they-can’t-shut-you-off policy. The authorities couldn’t or wouldn’t shut the electricity off between November and March. It was too cold and people could die without power. I grew up and still reside in the Midwest, where this “rule” is understood. I can’t speak for other parts of the country.

Many of our students live in households where the problems I faced are all too common. For many families, not paying a power bill in the winter is not negligence. It’s a time to catch up on other things, or to have a “good Christmas.” I’m not advocating this; I’m just saying that this is what people feel forced to do because they don’t have enough money.

I tell this story because teachers don’t always understand what students and their families go through. Perhaps my story can shed some light on the kind of topics kids don’t or won’t talk about.

To many of us, spring is a wonderful time of warmer weather and flowers starting to bloom. The world is coming alive again. But spring can also be a trigger, a time of stress. For some, April is more curse than blessing. Students may watch their parents scrambling to find financial help, or making arrangements to stay at the home of friends or family. This temporary displacement can be enormously disruptive for kids. It’s upsetting, it’s a giant distraction from their studies, and it can take a toll on participation in class.

I am now a 2nd-grade teacher at a school where many of the parents struggle to get by, where three-quarters of the children qualify for free and reduced lunch. Our test scores are among the lowest in the district. I teach there because I feel it’s where I belong. I can relate to many of the children in my school. I too was a poor, “at-risk” black student raised by a single mother. Thanks to my persistent mother and a few of the “dream teachers” I encountered in school, I was able to rise above the circumstances.

“Candles in April” was a moment in my life that was hard, but it made me strong. There can be strength in struggle and hardship. That time of my life taught me to be resourceful. But the effects linger in surprising ways. To this day, the smell of candle wax makes me cringe.

As teachers, on a daily basis we bring to class our backgrounds, our experiences, and our perceptions about the world. Sometimes the qualities and circumstances that make our lives “normal” do not match those of the students. Let’s remember that my world isn’t the only world that exists.