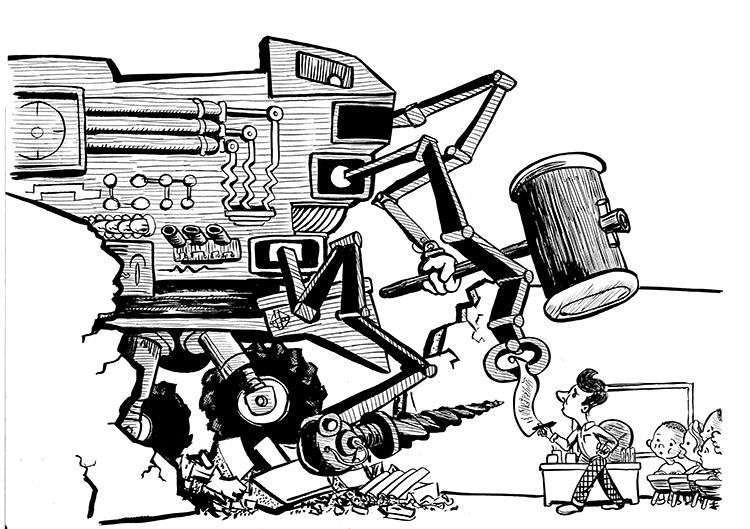

Can We Rescue the Common Core Standards from the Testing Machine?

Illustrator: Ethan Heitner

I hear this a lot these days: The Common Core State Standards (CCSS) are, in and of themselves, fine. If we could just uncouple them from the testing and implementation regimens, all would be well. The standards themselves are an improvement, so let’s build on that opportunity, and not stand in the way just because their ugly testing step-cousin is trying to sneak through the door with them. We just need to get rid of the high-stakes tests.

I can remember thinking like that. I can remember looking at the standards and thinking, “Many of these are actually fine.” In fact, one of my earliest complaints about the CCSS was that they were one more example of folks telling us to do things that we already did. And I don’t think there are teachers alive who don’t relish the promise of freedom to pursue standards in any way they deem most effective.

“You know,” I thought at one point. “If it were possible to just use these standards as a rough guide to follow as we thought best, and we got the government to stop testing, I could live with this.”

That was the same moment when I realized that, no, the CCSS were not pure of heart, and I would never learn to love them.

Because what would decoupling look like? What incantation would exorcise the testing demons? Could teachers go to the government and say: “Thank you for these guidelines. Trust us—we will use our best professional judgment and produce the best-educated generation of students ever. Just step back and watch us work.” No, that would never work, and it would never work because the CCSS are not for us. They never were.

Teachers who like the standards look at them as a guide, as that helpful assurance that we are on the right page. We think of standards as a tool to help us find our way. To us standards say: “Here’s a map. We trust you to find your way.”

Not the Common Core. The primary purpose of the CCSS is to call teachers out. It says: “Here’s what you are supposed to be doing, or else. And we’ll be checking up on you every step of the way.” It is not a tool to be used by teachers; it’s a tool to be used on them.

The CCSS say: “Here’s what you must prove you’re accomplishing.” If you tell your students that you expect them to study and learn the chapter about Torquemada and 15th-century Spain, they know there’s a test coming. Everyone expects the Spanish Inquisition. The CCSS are not about helping us teach; they are about holding us accountable, so they are meaningless without testing (and some parts are meaningless with it).

Since they were designed to hold teachers accountable, they were designed to be tested. Let’s look at the Reading Literature Strand for 11-12 grade: RL.11-12.1, 2, and 3 deal with key ideas and details, and all three standards have one thing in common—they focus always and only on the text. For example, RL.11-12.3 tells us to analyze the impact of the author’s choices, but not the intent or context of them. So a CCSS-style study of The Sun Also Rises would not include the impact of the Great War on Hemingway’s generation, Hemingway’s own background, the rise of postmodernism, or the emerging literary techniques of the period. Nor would we look at how prevalent themes of the generation find expression in the novel.

We would study The Awakening without applying an understanding of women’s roles in the fin de siècle American South. We would study the impact of sarcasm on “A Modest Proposal” without studying what prompted Swift to write it. Animal Farm would be a curious fairy tale about talking animals. I cannot even imagine how to unlock the riches of “Dream Deferred” or “I, Too, Sing America” without noting that Langston Hughes was Black, or considering what it meant then to be African American.

Why would we strip all this literature of its richness, depth, and complexity, the very human qualities that make it worth reading in the first place? Because measuring students’ grasp of such ideas would be hard. Because the test could not be standardized, because we could not control for the depth and breadth of background information that individual students brought to the table. Because the only serious answers to the only important questions would have to be in the form of essays instead of bubbles. And real essays (not the standardized faux essays) are not cost effective to score.

A standardized test cannot measure how a student understands Hemingway’s novel as an expression of a generation’s confusion and alienation after World War I. But a standardized test can ask a student to read a paragraph from the novel and pick the most important sentence.

These are not standards designed to foster a richer and deeper understanding of literature. They are designed to produce easily testable results.

You may reply: “You can teach all that other nifty stuff if you want. Go ahead and enrich your lessons above and beyond the CCSS.”

Well, if I am enriching above and beyond the CCSS, what do I need the CCSS for? If the CCSS is not laying out a path for a full, quality education, what path is it marking?

It’s laying out the path to the test. The CCSS are just the largest scale test-prep guide ever created. The CCSS tell us what we need to cover for the test, and the test tells us how well we covered it. If there were no test, the CCSS would not matter.

The CCSS are also, of course, about making money. No Child Left Behind (NCLB) also wanted to bust into the big piggy bank that is public school funding, but NCLB was a big, blunt hammer; CCSS is a more sophisticated machine with many interlocking parts.

In fact, the biggest reason that CCSS cannot be rescued is directly related to the difficulties those of us who write about education have had in explaining the problems with CCSS. And it is probably the biggest lesson that the powers that be learned from NCLB.

The mistake those powers that be made with NCLB is that they gave the whole thing a name. The testing, the state standards, the punishing evaluations, the funding pressures—everything was gathered under the No Child Left Behind banner. Oh, how we loathed it. We called it funny, mocking names. Even when we couldn’t see the full picture, we knew its name. We knew its name.

This thing that’s happening now? The contempt for teachers, the drive to privatize, the evaluation-based punishment, the dismantling of our profession, the destruction of public education, the redirection of billions of tax dollars, the secrecy, the ill-conceived standards—we can see all its pieces, but the great, chewing mechanism does not have a name. The lack of a shorthand title for the galumphing monstrosity allows its creators, our so-called leaders, to pretend that all these are separate elements, when, in fact, they are all one well-coordinated machine.

If these were all separate and discrete pieces, they could not be parts of a giant machine chewing apart the entire U.S. institution of schooling. And that leads to the belief that some of these separate pieces can be rescued—that we can accept some and leave the rest behind.

But the CCSS are part of a coordinated, interlocking machine, and its creators will never let you take only a piece of it home. The testing regimen is not its own separate thing that can be just thrown out, any more than it was its own thing when it was the engine of NCLB. If you want only one cog, you can’t extract it from the machine.